Chantal Akerman: Four Films

Massive film lover. Whether it's classic, contemporary, foreign, domestic, art,…

Chantal Akerman is a unique director whose minimalist compositions have earned her a reputation as one of cinema’s foremost screen artists. Best known for her 1975 film Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, Akerman’s body of non-fiction work stands out with deliberately punctuated documentaries, giving the term “fly on the wall” new meaning.

While Akerman’s body of work is varied, her vision of melding reality and fantasy are sometimes indistinguishable, and this omnibus of her work shines a light on an omniscient eye for capturing the world around us.

South – The Long, Painful Road

Judging by the name of the film, we know we are in the South, and playing the unintrusive observer is the role we assume in these documentaries from Akerman. The introduction to South (Sud) feels obscure in technique, but the structure and accumulation of information are delicately structured.

The more we see, the more it piques our curiosity, as we have long takes traveling down the roads of a Southern town. Also, there’s no narration. Title cards, music, or captions convey information, with our understanding coming from the informal punctuation that feels like it was influenced from Frederick Wiseman – though I would assume that this style is a naturally accumulated method from the director.

Once we arrive at the crux of the subject of South, it’s a jarring realization; the tranquil setting is the location of the James Byrd case. A brutal incident that took place in 1998, Byrd, a 49-year-old black man, had been abducted by three white supremacists, beaten and chained to the back of a pickup truck for three miles until his death, with his remains then dispatched to the front of an African American cemetery.

The inhumanity of this act violates our senses, and the sadness and frustration that accompanies this information is painful. You reflect upon the unfettered delivery of the information by the officer, grow infuriated with a sheriff who claims that Jaspar, Texas has less racial problems “than most places in the country”. Frustration grows when he follows that comment by calculations, ratios and other bureaucratic excuses to justify racial inequality, and you have to ask yourself a series of questions, that sadly we don’t have an answer to – where does the hatred come from, why are these things still happening, are we still this bad?

The symbolic correlation of the long vistas of the open road transcends abstraction to distinction, so specific the footage conjures up a profound emotional response that feels appropriately abusive to the viewer.

The information is difficult, and we think the atmosphere will worsen when encountering the victim’s funeral service, but the climate changes for the better because we feel an emotional response to the victim’s life and the people he touched. It’s a somber setting, but in the face of so much grief we have pacifism instead of more hatred, and a community who has every right to be incensed is sustained by their faith. Afterward, we are back on the road as if we need more time to digest the information. We wonder where this road will lead to, and as racial tensions continue to mount in America we have to ask: when will it end?

From the Other Side – The Land of Opportunity

The resonance of abstraction captures a unique brand of truth in Akerman‘s nonfiction films, and her open-ended way of documentation works brilliantly with the 2002 film From the Other Side.

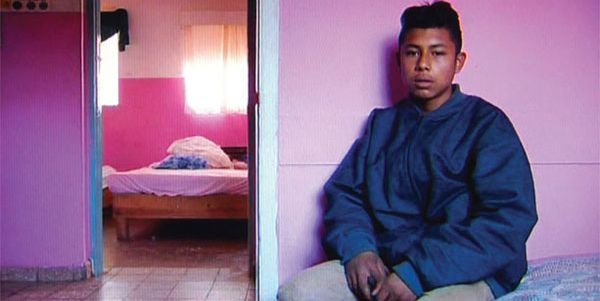

We travel farther south to border towns in Arizona, those who have made the journey from Mexico to America only to be detained, caught, or simply disappear. The commentators come from both sides; American border patrols, sheriffs, preach incensed September 11th paranoia, contrasted against the footage of interviews of families from Agua Prieta and Sonora, whose relatives and friends have made the journey without actually knowing where or what has happened to them.

Like South, the footage in From the Other Side opens the discussion to a bigger problem at hand, and that is the amount of people whose desperate economic situation compels them to risk their lives to find a better one in America. This is further complicated by the hypocrisy that arises from intolerant border patrols and immigration laws initiated by a country founded on that very ideal.

Our canvas here is broad, and the long takes once again carry a great deal of insight; the border itself becomes something of a character, and even at a distance the barbed wire and foreboding darkness is an imposing reminder of American insincerity and historical connotation. Another memorable scene includes a long take capturing the busy traffic in-between borders, reminiscent of Jean Luc-Godard’s famous traffic sequence in Weekend, only toppled by the fact that this is the real world.

Là-Bas – Tel-Aviv

Almost all of the footage that comprises Là-Bas was recorded from the interior of an apartment Akerman had rented while she was teaching in Tel-Aviv, Israel. The bulk of the film consists of long shots through a thinly veiled window as she provides infrequent narration off camera. Her musings range from the profound to the banal; sometimes she mentions her neighbor watching their plants grow, to her personal experiences regarding her familial history (she is the daughter of Holocaust survivors), to her aunt’s suicide, correlating her past with the report of a suicide bombing nearby.

When producer Xavier Carniaux (who’s credited as producer for these three projects) proposed the idea of shooting a documentary about Israel while she was staying in Tel-Aviv, Akerman was reluctant but used the offer for her conceptual observation.

When directors document a distinct location, they usually attempt to “transport” the viewer in an experiential manner, but Là-Bas achieves in the opposite direction by taking us into the psychology of its informal subject of spiritual malaise and conflicted cultural identity.

It’s as if Akerman were protecting the sanctity of Israeli identity by recording from such an enclosed space – as if the abstraction of humanity had already occurred by the tumultuous conflict in Israel. We could speculate on the film’s message, and like many works of art there’s several different ways to analyze Là-Bas and its modest expressionism, but the significance of this movie lies in its experiential value.

You can’t call this a “documentary” or a “political” piece since its only externalized political ideas come from second-hand stories voiced by the director, who never appears on screen. The treatment of its informal subject is polarizing by the lofty interpretation, unafraid of its potentially divisive aesthetic. Somber, but rewarding spiritual artistry.

Chantal Akerman, From Here – A Portrait of the Artist (from the next room over)

These three films directed by Akerman provide a better sense of her style as a director, so following South, From the Other Side and Là-Bas I was eager to learn more about this singular filmmaker.

With two directors credited (Gustavo Beck, Leonardo Ferreira), Chantal Akerman, From Here feels like an attempt to recreate Akerman‘s style of filmmaking, by shooting an interview from the next room over in a single take. Her insights are candid and fascinating to hear, but it sabotages the significance of the information – it’s not that we need someone to hold our hands, however, but for a feature length interview the dialogue is essential. What good can all this insight be when you can’t make out what’s being said?

Regardless, the film being handled as a bonus feature is a pleasant follow up to these three titles. Despite being compromised, it’s hard to resist the enigmatic charm of someone who is this clever and brazen.

Conclusion

For the films of Chantal Akerman, it’s more fitting to treat them as you would an installment piece rather than conventional narrative, simply because these titles don’t have much to speak of. That’s not meant in a reductive way either, because these are great works of minimalist cinematic art. Applied to the documentary form (if you want to call them that), Akerman is the opposite of an alarmist sounding board for political issues, a deafening drawback that is all too common in documentaries centering on political issues.

Consider that the popular films which explore hot-button issues by directors such as Alex Gibney or Michael Moore tend towards explicit visual accentuation or staged recreations to convey their messages. But when you delve into the nonfiction works of Chantal Akerman, you find her counter-intuitive treatment refreshing and brave.

Have you seen any of Akerman’s films? If so, which is your favorite?

The Chantal Akerman: Four Films Box Set is available on Home Video and DVD!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Massive film lover. Whether it's classic, contemporary, foreign, domestic, art, or entertainment; movies of every kind have something to say. And there is something to say about every movie.