For 2012’s Leviathan, directors, and founders of Harvard University’s Sensory Ethnography Lab, Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel, fastened GoPros to both themselves and throughout a commercial fishing ship somewhere in New England waters. The film, which ends with a lingering shot from a camera bobbing in and out of the midnight sea, was created out of a process of unpredictability — place cameras everywhere, edit the footage into a film. The result was one of the most canon-worthy, medium-bending films of its decade.

Castaing-Taylor and Paravel, anthropologists by trade, built a similar unpredictability into their latest documentary, Caniba, which is, in the abstract, a profile of Issei Sagawa — a legally insane Japanese man who, in 1981, murdered, raped and cannibalized a Dutch woman — was shot without any understanding of Issei or his caretaker brother Jun’s dialogue. Their words have been translated for non-Japanese speaking viewers, but the filmmakers did not allow the content of the brothers’ dialogue to guide filmmaking decisions. Following its NYFF 2017 screening, Castaing-Taylor said this choice was inspired by wanting to “achieve a more corporeal engagement with their subject.” They weren’t interested in making another document about cannibalism that focuses on the act, Paravel continued, but rather trying to capture a more subjective register of a cannibal figure.

A Different Kind of Profile

The act of profiling a living figure marks a distinct break between Caniba and Leviathan, which only featured humans on the film’s periphery. And, if one was inclined to rope in 2009’s Montana cattle documentary, Sweetgrass, which only half of the duo had a hand in, you could draw from further in time a lack of auteurist interest in humans, or at least, what they’re willing to say to documentarians, instead focusing on the characteristics of their environs.

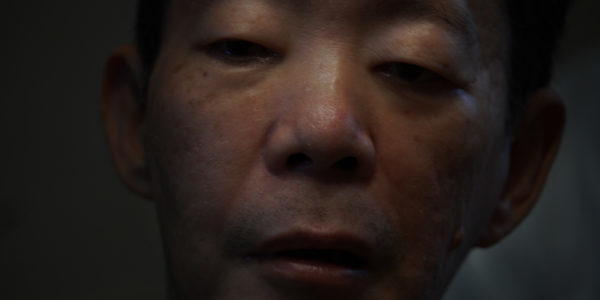

In Caniba, the landscape is Issei and Jun’s faces. The majority of the film is shot in extreme close-up, both in and out of focus. Apparently the directors also shot more establishing footage of Issei’s apartment, but that was slowly chipped away during the editing process. The removal of such footage, which would help us orient the figure in their space, leaves us with a tactile, and often gross, aesthetic. But, if you resist the brothers’ skin as its own landscape, the only alternative is claustrophobia.

Castaing-Taylor attributes the film’s visual style to a couple things. Primarily, the duo were interested in how “people’s faces and heads express aspects of their identity, being and past in ways that aren’t communicable by language.” Less importantly, they were challenged by a friend to make a more traditional talking-heads documentary — not exactly how anyone could reasonably describe the finished film.

Another non-traditional treatment of a traditional stamp of cinematic nonfiction is the presentation of secondary sources. Childhood home videos, homemade porn and fetish videos all play integral parts in Caniba, revealing histories as well as current lifestyles. But the filmmakers, revealing themselves as the anthropologists they are, remediate these videos with their camera. In doing so, we aren’t granted an omniscient, objective exposure, but a look through the eyes of another viewer — in this case, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel’s subjectivity.

A Brothers’ Dialogue

Though Issei is the marquee subject, the second half of Caniba takes a wide detour into Jun’s life. Quite suddenly, the camera is panning barbed wire, intimately surveying its texture before we see Jun using it to sexually gratify himself by wringing the wire around his arm, followed by footage of Jun biting, stabbing and burning the same area of his upper-arm — not any candles will do, he says, only altar candles burn at an appropriately hot temperature.

Castaing-Taylor and Paravel say they didn’t know this aspect of Jun’s life, and thus didn’t expect him to reveal them. And, logically, since they didn’t know what he was saying at any given moment, the filmmakers’ decisions were presumably dictated by context clues and instinct. Paravel actually supposes that it took their presence as filmmakers, with a record, for Jun to not only discuss the particulars of his own fetishes, but to engage with his brother and their relationship, past and present.

Interestingly, where their previous works exhibit a lack of interest in what men are willing to say to a camera, the directors’ presence here as recorders ends up pulling out words from Jun that he otherwise hasn’t been willing to divulge, and Caniba ends up driven by his confessions and candor.

An uncomfortably long stretch of the film involves Issei going page-by-page through his published manga detailing the rape, murder and cannibal devouring of his real-life victim. Jun can only take so much before he’s audibly disgusted and repeatedly tells his brother he disapproves of its publishing. Jun is similarly outmatched when, after revealing his own fetishes to Issei, is greeted with a non-reaction. For as much time as Issei and Jun spend together, we get the sense they don’t know each other very well.

An Anthropological Investigation

Because Castaing-Taylor and Paravel have withheld live interpretation and are figuring out details of their figures’ lives along the way, Caniba has a sense of exciting, albeit often scary — I’ve never thought the phrase “Can I show you some video?” was ever as frightening a proposition — exploration rather than didactic explanation. The built-in unpredictability of their previous two features are more indicative of textual and anthropological investigation than storytelling.

However, as stated, the film remains thematically propelled by the same overwhelming sense of loneliness found in the bowels of Leviathan’s boat. “I’ll probably die not knowing why I like it or if there’s anyone else like me,” says Jun, referring to his fetish for torturing his arm. Sentiments like this, when so plainly spoken, strip his kink of sensationalism and cut straight to the more primary issue of living with such stigmatized fetishes: profound loneliness.

Ending with a parallelization of Issei and Dracula may seem cute and on the nose — like footage too good not to use — but considering the monstrous isolation of Bram Stoker’s fictional bloodsucker, their equivalency becomes more poignant than a superficial taste for human flesh.

Of course, our feelings toward Issei and Jun’s respective loneliness may vary drastically, considering the former’s reprehensible past and lack of remorse, and the latter’s kindness — at one point, he laments not being able to help more responsibly satiate his brother’s desire, asking if he would’ve obliged his own arm (which he elsewhere describes as his sex organ) to Issei’s teeth.

Caniba: Conclusion

Perhaps the film’s title can shed some light on the filmmakers’ position. In Abby Sun’s terrific feature in Film Comment’s September-October issue, she states that “Caniba” is a reference to Christopher Columbus and “his misunderstanding the Carib language word for people, which became the root of the English word ‘cannibal.’” This reference itself, a mistaken overlapping of people and people-eater, appears to be a comment on the binaristic idea that reprehensible people are too often misunderstood as monsters, or not people. This doesn’t mean that Castaing-Taylor and Paravel consider Issei a sympathetic figure — this viewer came away disgusted by him, but dismissing him as a monster feels too neat.

Sun, a former student of Castaing-Taylor and Paravel, said the two, as production teachers, assigned a project titled “Dare to Desire,” which pushed students to produce taboo films that traversed their level of comfort and, just as often, disrupted student complacency. “[T]he rarity of this approach is evidence that vulnerability and desire, and their necessary presence during the filming of exceptional subjects are underutilized angles of inquiry for documentary filmmakers,” she concluded. Caniba isn’t the mammoth achievement of Leviathan, but, by taking their own command and placing themselves in uncomfortable and unfamiliar situations, the filmmakers have cobbled together another, and altogether differently, disturbing film about human loneliness that feels rare in documentary’s contemporary canon.

Caniba is released to limited theaters in the U.S. on Oct. 19, 2018. Find more information here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.