BY THE TIME IT GETS DARK: Fulfilling The Possibilities Of Film

I'm a writer, artist and teacher based in Manchester, England.…

Doppelgängers, psychedelic mushrooms and political protests inform Anocha Suwichakornpong’s intriguing new offering, By The Time It Gets Dark, but is it more than just a cinematic curio?

The Realm of the Postmodern

By The Time It Gets Dark defies categorisation in terms of genre and narrative structure. It also defies simple explanation. Yet rather than leading to frustration, this is a film that unshackles itself from conventional narrative constraints and surprises with almost every frame.

The film’s starting point is the student massacre at Thammasat Univeristy in Thailand on the 6th October 1976, following the controversial return of a former military dictator. In Thailand, this is often referred to as the 6th October event but this would suggest far more factual precision than the way it is treated by Suwichakornpong’s film.

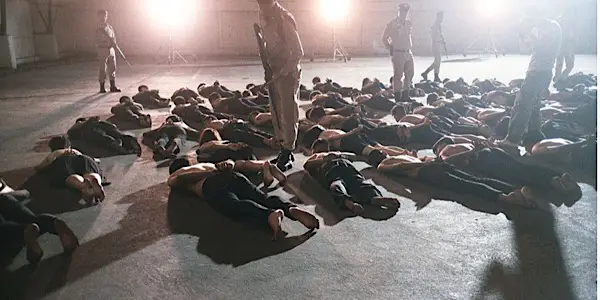

There is no soundtrack on the opening credits or during the early scenes. What initially appears to be footage of the massacre is gradually revealed to be a re-enactment being filmed for an unspecified project. It is here that we are introduced to Taew, a young articulate female student at the heart of the campus revolt.

At the outset, confused by the sparse descriptions and summaries I could find about the film, I expected the inclusion of real footage and perhaps a more conventional documentary style leading towards reflections of a more fictional nature. Instead, we are shown that right from the start we are witnessing a film within a film; a film still being made about the same subject within a film about the same subject. There is no easing in: we are in the realm of the postmodern.

Multitudes

Each time we are presented with a person or a place, the camera eventually pulls back and either teases, suggests or reveals that what we currently see on screen is but one version among many. By The Time It Gets Dark is a film of multitudes. There appears to be several different versions of both central characters – Ann, who is sometimes a documentarian (played by Visra Vichit-Vadakan and others) and Taew (played by Rassami Paoluengtong and others), who appears at different ages, ghosting in and out of Ann’s existence. This is disorienting all the way through By The Time It Gets Dark and only becomes clearer afterwards.

Some scenes, such as the interviews, are direct and have a realism that borders on faux reportage. Other scenes are Zen-like and characterised by beautiful light, wild rural landscapes or the poignancy of domesticity. At times, this feels like a more sincere and less pretentious evocation of Malick’s recent work: it has the same metaphysical scope, yet it wears it lightly. The characters’ intentions and desires remain elusive.

Reflections and Psychedelia

There are recurring themes. Every frame is gorgeous but not in a self-consciously stylised way: the simplicity of the countryside, the sky or a modern interior are all allowed to speak for themselves. Yet for all its subtle revelations of landscape and framing, the film also has a mysterious opacity, frequently showing the main character in reflections of windows, mirrors, as seen through the eyes of another or trapped in the hall of mirrors of the forest when she glimpses her doppelgänger.

The interview scenes are filmed through a window, the perspective of the camera looking into the room while the interviewer’s camera is pointed out the other way, towards Taew and beyond to the outside. We see the stunning landscape reflected in the glass wall as exterior and interior merge in the same way that the past and present are interlaced here too. The boundaries blur quite literally.

There is also an interplay between that which hides and that which is revealed, and how both aspects, although apparently opposite, can be co-dependent on each other in order to define themselves. Ann says Taew is living history whereas she declares herself as mundane, condemned to chronicle rather than to live life. It is her job to make By The Time It Gets Dark. The most intimate and organic moment they share is in the darkness during a power cut. When the lights return the revolutionary quickly retreats.

As past and present, interior and exterior, the real and the recreated begin to rub up against each other, otherwise innocuous references to harvesting fungi culminate in a sudden slide into the unravelled maw of psychedelia. The viewer feels the considerable force of this disorienting effect as a simple stroll in the woods, apropos of nothing, is disrupted by the inexplicable appearance of a young girl in a tiger onesie, followed by Ann’s Doppelgänger. It is only afterwards that we see her examining a bright sparkly mushroom with which she seems infatuated. Is Ann literally running away from herself, or perhaps just her mundanity?

The Spaces Between Events

By The Time It Gets Dark is also a film of spaces, physically empty ones but ones that are suffused with significance. The viewer’s mind is already gambling in the incoming stream of wonderment when, for example, a character returns home to his apartment. We view the scene from the perspective of a static camera so when he leaves the room to visit the bathroom, we only hear him, remaining focused on the empty living area he has vacated until he reappears. At once, the empty room, devoid of soundtrack apart from the water running in the bathroom, is filled with our thoughts.

The room cannot simply be; it’s like the universe itself, once perceived we stuff it with our values and when we realise that they are only our values, we feel the icy depths of the abyss. Isolation is a recurring theme throughout and the whole film is steeped in a melancholic mood where single figures gain poignancy by being surrounded only by inanimate objects, whether they are kitchen appliances or a highly realistic menagerie of synthetic animals. As she moved between their pink stilts, was the main character thinking of those flamingoes as the people she encountered day by day: not real enough to connect with?

By the time Ann records an interview with herself in which she talks about once doing telekinesis but never managing it again, the viewer may be wondering how much of this is real and how much began when she was offered oyster mushrooms at the cafe?

Solipsism or Interconnectedness?

Here, amidst all the confusion, we have a statement on art and the art life: somehow, whomever or whatever the supposed subject, the artist is only ever really exploring herself. Unavoidably. And not necessarily narcissistically. What emerges here, contrary to that, is more like the suggestion of inter-connectedness, a holistic, now often derided perspective, that we are all part of some universal.

The impetus for Ann’s film was the coup of 76, a cognate of the Vietnam protests or Paris ’68. Again, a swathe of culture associated with eastern explorations, notions of the universal and psychedelics such as mushrooms. Hippies and the summer of love may have been out of fashion since a brief renaissance in the late 80s/early 90s acid house scene, but with states turning their backs on nuclear non-proliferation treaties and a resurgence in fascism, this subtle revisit is crushingly apposite.

In fact, this film pleases in its strangely confrontational stance towards the times: its speed is meditatively slow. It exists in a different place that is both relevant and yet you get the sense of both characters being out of time/out of place in this rural hinterland.

By The Time It Gets Dark: Conclusion

It is an unforgettable but enigmatic ending as the shots of the dancefloor distort in time with the harsh refrains of the Balearic beats until we are left with the presentation of an unexpected and unexplained wild vista, the sky a computer crashed negative red before colour returns to normal. Nothing moves except for the foliage swaying in the breeze. By The Time It Gets Dark imitates life. We are left to impose our own narrative structure. This is a cinematic classic that will beg to be watched, decided and marvelled at, time and time again.

Do you agree that experimental cinema such as this more readily captures the dynamism of modern life, or are switches between times, places and perspectives detrimental to the viewing experience? Tell us your thoughts in the comments below!

By The Time It Gets Dark was released in the U.K. on June 16th. In the U.S. on September 19th. For all international release dates, see here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

I'm a writer, artist and teacher based in Manchester, England. My debut novel is entitled Look At What You Could Have Won and you can find extracts from it, along with my Anti-Reviews, original fiction written in response to art and cultural events, on my blog: This Is Not A Film Review.