BROADCAST SIGNAL INTRUSION: A Tale Of Obsession

Brian Walter is a college professor by day and a…

Hast seen the white whale?

Captain Ahab distills all of his fateful obsession with the sea monster that dismasted him into this simple but endlessly resonant question. Herman Melville’s most tragic hero puts it immediately to every other shipmaster he encounters, dead-sure that anyone else who has seen his eerily-blanched quarry will, of course, share his metaphysical rage against Moby-Dick.

But Ahab is not just seeking revenge. Still more, the captain of the Pequod is hellbent on wringing meaning from his loss, using everyone and everything around him to make the whale’s humiliation of him somehow illustrate and uphold the increasingly desperate truths in his mind. For a true obsessive like Ahab, reality becomes a series of signs that, if properly and faithfully decoded, all point to the omnipresent but elusive object that so relentlessly and gleefully burns away his mind.

It is a handsome compliment to Phil Drinkwater and Tim Woodall, the directors of Broadcast Signal Intrusion, a ‘psychological horror’ short, to say that they have achieved a similarly compelling story of obsession in a mere 15 minutes of screen time. Their grieving protagonist could do Ahab proud in his need to force meaning from his grief and anger — by violent means, if necessary.

A Loner’s Obsession

The short film opens with a shot as stark and even iconic as it is horrifying: an auburn-haired woman in white, seen at a helpless distance from behind as she stands at the edge of a skyscraper’s roof, etched against a cloudy sky and other skyscrapers in the distance. Already terrified to anticipate the leap she is about to make, we wish immediately to see her face, to read there her thoughts and frame of mind as she stands on the edge of the precipice. Cleverly, the directors only partly fulfill this wish.

We soon learn that this opening tableau is the dream — or nightmare — of our young male protagonist. He lives in a small room, desk cluttered with books and computer, a modest modular closet/wardrobe in the corner, and his sleep-tousled head on the bed pointed toward the partly-curtained window which shows only grey sky out of the lower right corner. Is he truly a loner, one immediately wonders, or just deliberately (and unhealthily) alone?

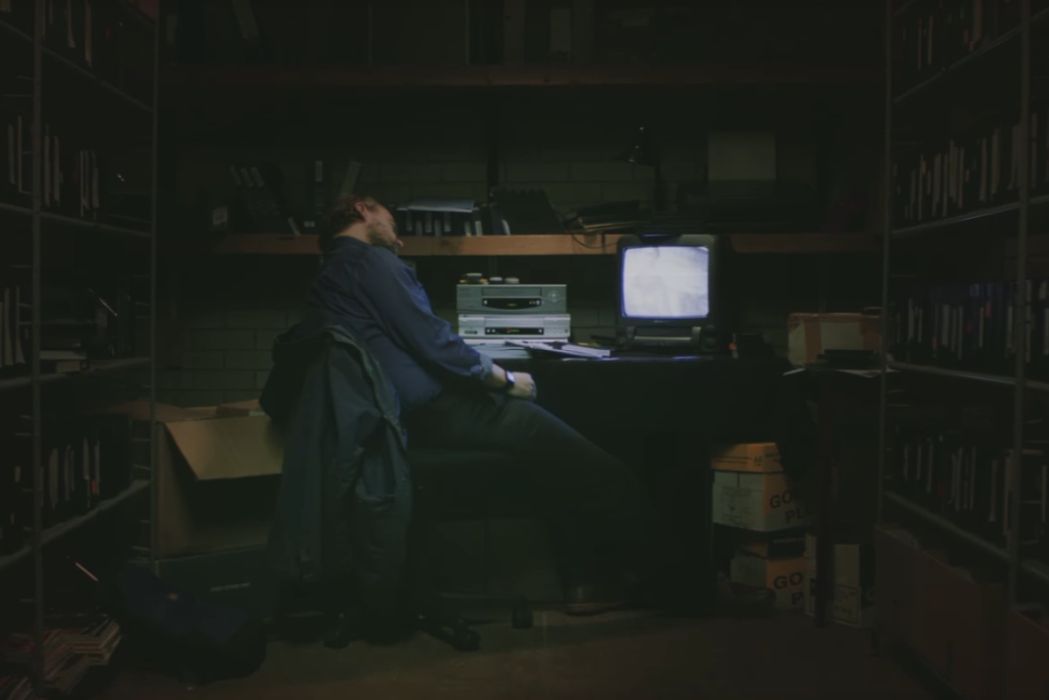

The next sequence, ominously labeled ‘September 2001,’ hardly provides an encouraging answer. We see him at work in a basement video library, labeling and cataloging VHS tapes: dark, quiet, lonely work, the tapes audibly popping in and out of the spring-controlled doors to the player, the workspace a clear reflection of his dark, quiet, lonely home and life. We soon see him from above and behind, briefly in the twilight, as he walks home from work, backpack over his right shoulder, pulling the hood over his head against the night, but really, it is already apparent, against the forces of fear and isolation so vigorously at work inside him.

He speaks with his father on the phone, and the lighting, cutting, and camera placement all cleverly, subtly suggest stark differences in their responses to the event that has apparently prompted the nightmare of the woman. When the older man attempts, gently, compassionately, to help his son try to start developing some perspective on the loss that haunts him, our protagonist has to hang up, unable, as he says, to talk about it right now.

This is his life: boredom, anguish, and alienation from others and himself, a Dostoyevskian underground man dooming himself to remain alone in the dark indoors.

Confrontation and Crisis

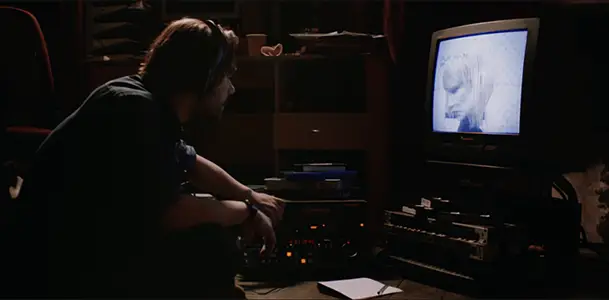

Until one evening, nodding off in front of the screen in his basement work cave, he is startled awake by a clip of a bewigged female mannequin in a bizarre dollhouse set that has been unexpectedly interpolated into the educational show he had been reviewing. The intruder of the title has arrived.

But the protagonist only realizes (or resolves) that he has, in fact, finally glimpsed his white whale after he attends group therapy. There, he hears a middle-aged woman claim, of her own loss, that maybe there is no sense to be made — unless she just didn’t look hard enough. He runs off immediately to find the signs he’s been desperately looking for in the intruder clip, and sure enough, he detects a flicker of information that he missed the first time. His inner Ahab now has the clue he has needed, the sign within which he can finally make out the contours of the white whale of a truth that he has been hunting so long and futilely.

The confrontation that follows is as inevitable as it is horrifying. When our obsessive griever finally has, as he believes, his tormentor helpless and cowering before him, he cuts him off sharply: “Shut up! I said, be quiet!” The signs he has found (or invented) say all that this young, emotional obsessive needs; he has no use for the living human voice.

The final sequence of the film completes the circle as deftly and painfully as the preceding scenes have detailed the protagonist’s fateful obsession. If these final scenes resort to the kind of rapid, disorienting cutting that too often, in horror films, seeks a quick, easy way to ratchet up the viewer’s pulse and tension, the film has earned these rather clichéd techniques with its graceful character work and effective visuals throughout.

From the buzzing, halting, flickering appearance of the overhead fluorescent lights outside his basement work-space early in the film to the carefully imbalanced two-shot of the obsessive facing his terrified scapegoat in a dimly-lit flat near the end, the directors find numerous visual registers to enhance this story of obsession.

One of my favorite bits has the protagonist repeating one of replicant-hunter Rick Deckard’s signature moves in Ridley Scott’s gloomy 1981 sci-fi noir, Blade Runner. When Deckard removes his quarry’s quasi-bridal veil, he indeed finds what he has been seeking, but the tantalizingly-shot counterpart-scene in this film cleverly leaves the viewer with some doubts.

Obsessive Meanings

It would be possible, taking a step back from Broadcast Signal Intrusion, to raise some unsettling questions about its treatment of women. Do they — can they — exist only as imaginative conveniences in this film, little more than a spur to our male protagonist to finally turn his obsession into action? Is he capable of recognizing and responding to women as whole human subjects in their own right, or only — as he does with the supposed oracle in the therapy group — taking the one small part of what they voice that best feeds his pain-constricted agenda?

But such questions, as legitimate as they may be, cannot take away the film’s finally clear-eyed and subtly compassionate dramatization of the manifold, even ruinous costs of true obsession. The absence of women characters from Melville’s great fish story finally only magnifies Ahab’s tragic imbalance, and this short film achieves an impressively similar effect.

Obsession in this film too enfolds its designs on revenge into a grander and far more hopeless epistemological quest for ultimate meaning, and if the cosmos won’t provide those answers directly, then the wronged, determinedly self-justifying obsessive will create them for himself — in true tragic form.

Has the obsessive found his answer?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcoUgUGv8d0

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Brian Walter is a college professor by day and a hopelessly sleepy college professor by night. His work has appeared in a variety of literary and film studies publications, and he appears as an 'old coot' interviewer with a magic camera in the final chapter of Donald Harington's final novel, "Enduring." He lives a short walk from the St. Louis Zoo with his remarkably patient, loving wife and a quirky assortment of canine and feline familiars.