When I was 10 years-old, I had the good fortune of seeing Queen live. They were at the top of their creative powers, with band squabbles and the untimely death of lead singer Freddie Mercury still years away. Thirty-five years and hundreds of concerts later, it remains my favorite concert experience to date. The sights, sounds, and setlist may have faded in my memory, but the image of Mercury prowling around the stage like a deranged opera singer remains burned into my brain.

It is with great sadness, then, that I must report the new Queen biopic, Bohemian Rhapsody, is a crushing disappointment. It’s ironic that a film boasting the tagline “Fearless Lives Forever” is so utterly milquetoast. What director Bryan Singer has created is the cinematic equivalent of a Greatest Hits album; cherry picking band milestones, re-arranging chronologies, and sugar coating the drama in order to manufacture the most commercially viable product possible. Casual fans might enjoy pumping their fist to some raucous concert re-enactments, but those seeking insight into the band’s creative and personal history, particularly that of Mercury, should look elsewhere.

“Legends Aren’t Born, They’re Built”

Perhaps Bohemian Rhapsody was doomed from the start. Preparations for a Queen biopic began nearly 10 years ago, with a tantalizing list of names rumored to be attached, including uber-director David Fincher and uber-prankster Sacha Baron Cohen slated to play Mercury. After Rami Malek came aboard as Mercury with Bryan Singer (X-Men: Apocalypse, X-Men: Days of Future Past) to direct, and Queen alums Brian May and Roger Taylor signing on as musical consultants, production finally lurched forward.

It was a production plagued by delays and the dreaded ‘creative differences,’ mostly attributed to Singer’s increasingly erratic behavior. Finally, in December 2017, Singer was fired due to “a personal health matter” and replaced by Dexter Fletcher (Eddie the Eagle) with only two weeks remaining in principle photography. With the possible exception of Stanley Kubrick assuming the helm of Spartacus, Hollywood history records that changing directors mid-production is a disaster waiting to happen.

It’s not the personnel or production problems that cripple Bohemian Rhapsody, however, but the superficial approach to its subject matter. In the immortal words of Arnold Schwarzenegger, “Legends aren’t born, they’re built!”. Singer and screenwriter Anthony McCarten ignore the building blocks and nuance of Mercury’s legend, settling for made-for-television melodrama that will neither challenge nor inform.

Mercury, whose flamboyant public persona was fascinatingly at odds with his reclusive off-stage existence, feels like a finished product here. The years of honing his stage presence in dead-end rock bands is conveniently ignored. As if dropped from Heaven, he magically appears to May and Taylor just moments after the lead singer in their startup band (named Smile) decides to quit. It’s the type of convenience that plagues Bohemian Rhapsody, which rearranges Queen’s history to suit the needs of its lackluster plot.

Gone, too, are all of the details regarding Mercury’s early family life. Born Farrokh Bulsara to Parsi parents who fled the Zanzibar Revolution, Mercury settled in England when he was still just a teenager. Undoubtedly, his rebellious search for identity and acceptance brought him into conflict with his parents and their strict Zoroastrian beliefs.

“Good thoughts, good words, good deeds,” his father reminds a young Farrokh of the Zoroastrian tenet. Unfortunately, it’s one of only three brief scenes featuring Mercury’s family, who re-appear to be disapproving or accepting, depending upon the plot’s requirements. Had Singer been more interested in a nuanced examination of Mercury’s sometimes reckless life choices, this moralistic upbringing might have forced Mercury to acknowledge his inner conflict. It’s called ‘drama,’ and Bohemian Rhapsody has none of it.

“Love Of My Life”

Singer opts to add depth through a much safer cinematic device; a doomed love affair. It’s not a bad notion, as Mercury’s complicated relationship with friend/lover/wife (maybe) Mary Austin (Lucy Boynton) is ripe with dramatic possibilities. Mercury stated publically that Mary was his only true friend, going so far as to call her his common-law wife. If anyone was truly capable of seeing the man hiding behind the performer, it was Mary.

Sadly, this version of Mary is nothing but a cynical reminder of the heterosexual lifestyle that Mercury ‘rejects.’ She isn’t there to be the confidante who helps Mercury understand his sexuality or find his true identity, but to drift in and out of his life, tormenting him with yet another relationship that he can’t have.

Still, the film’s few genuine moments of humanity revolve around their peculiar relationship. Take the delicate scene in which a lonely Mercury makes a late-night phone call to Mary (who lives in the house that Mercury purchased for her next door). Feeling empty after the din of his house party has faded, Mercury cajoles Mary into flipping her lights on and off to match his cadence. Yes, it’s a playful game that Mercury would re-create thousands of times on stage (challenging the crowd to replicate his impossible operatic flourishes), but it’s also a heartbreaking reminder of his desperate search for connection.

Mercury’s connection to his bandmates is even less defined. Singer seems content to have physical impersonations of May (Gwilym Lee), Taylor (Ben Hardy), and bassist John Deacon (Joseph Mazzello) rather than functional secondary characters. Aside from providing the occasional (and much needed) comic relief, the members of Queen exist only to marvel at Mercury’s brilliance. May eyes Mercury like a smitten puppy as the two rip through stadium standards like “We Are the Champions” and “Hammer to Fall.” There are brief glimpses into the band’s sometimes temperamental relationship, as when Mercury departs to record two solo albums, but mostly the inflated egos of these multi-millionaires have been sanitized to preserve the lovefest.

Artistic License

If Bohemian Rhapsody stuck to just the facts, it would be a documentary, and documentaries don’t pack theaters. With that in mind, the filmmakers take plenty of liberties with the band’s chronology and the personal details of Mercury’s life. This can be as harmless as the inaccuracies only a true fan would recognize (“Fat Bottomed Girls” being recorded before A Night at the Opera and “We Will Rock You” coming after 1980, for instance) to shameless emotional manipulation. The most egregious example of Singer’s pandering is a fabricated scene in which Mercury reveals his HIV diagnosis to bandmates just prior to their thunderous performance at 1985’s Live Aid concert. Clearly, the filmmakers will stop at nothing to extract a few tears from the audience.

Singer also makes infuriating usage of montages to cut narrative corners, including a psychedelic interpretation of Mercury’s foray into the gay nightclub scene. It’s debatable whether scoring this montage to Queen’s disco anthem “Another One Bites the Dust” is distasteful, but there’s no denying Singer wants to avoid the seamier side of Mercury’s sexuality.

This appeasement of squeamish viewers goes to almost laughable lengths. Mercury’s first dalliance with men, for instance, is locking eyes (in slow motion, no less) with a random man entering a public restroom. You can almost see Singer winking at the camera saying, “Yep, he’s gay now, but we don’t need to see any of that.”

Even more offensive is that the predominating symbol of homosexuality is Mercury’s sleazy personal manager, Paul Prenter (Allen Leech). Prenter is the unmistakable villain of Bohemian Rhapsody. He isolates Mercury from his bandmates and Austin, even refusing to take the call from Bob Geldof about performing at Live Aid. Regardless of the accuracy of Prenter’s villainy, he becomes the leering face of gay promiscuity; a damage that even the introduction of Mercury’s eventual partner, a thoroughly decent man named Jim Hutton (Aaron McCusker), is powerless to undo.

Bohemian Rhapsody: Conclusion

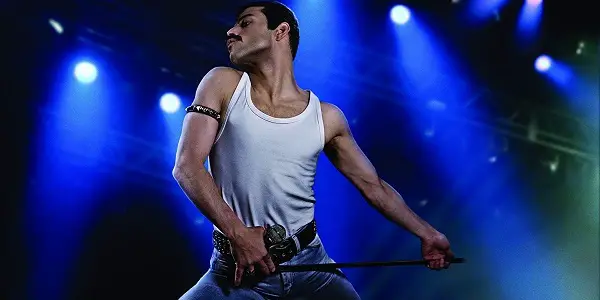

So what’s good about Bohemian Rhapsody? Rami Malek is good… really good. He thoroughly inhabits the c*cksure performer, nailing all of Mercury’s signature postures and gestures. As for Mercury’s unmistakable voice, an amalgamation of Malek, recordings of Mercury, and a singer named Marc Martel create a passable facsimile, though the lip synching is sketchy at times.

The performance set pieces, too, are often fantastic. Standout sequences include the recording sessions for “Bohemian Rhapsody,” which finds Mercury pushing his bandmates to ever greater heights (and Roger Taylor’s voice to ever higher registers), and an epic finale featuring Queen’s appearance at Live Aid. Watching the nearly perfect re-creation of Queen’s triumphant performance leaves you wishing that the previous two hours of Bohemian Rhapsody weren’t such a disappointment. Mercury deserves a film that isn’t afraid to tell his story, even if it means selling fewer tickets.

What’s your favorite music biopic? Share your thoughts in the comments below!

Bohemian Rhapsody was released in theaters in the UK on October 24, 2018 and the US on November 2, 2018. For all international releases dates, see here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.