Black Mirrors: Smartphones & Cinema

Brian Brems is an Associate Professor of English and Film…

The smartphone era of cinema arguably begins in the closing moments of David Fincher’s 2010 drama The Social Network. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg) sits alone in a conference room after a grueling fight with his former best friend over the ownership of the site’s intellectual property. Using his laptop, Zuckerberg logs in to his own creation and clicks ‘Add Friend’ on Erica Albright (Rooney Mara), the ex-girlfriend he does verbal battle with in the film’s opening scene. He refreshes the page. He refreshes it again. He keeps refreshing into the film’s text epilogue, which traces across the screen next to Zuckerberg’s head.

Fincher’s film attempts to capture the dynamism of the social media age as he brings Aaron Sorkin’s frenetic script to life through striking image composition and collage editing. But the film’s most enduring image is Zuckerberg’s lonely last moment in the conference room, refreshing the page on his laptop, desperately seeking the human connection he feels he’s lost throughout his legal dustup. The spinning wheel – loading, refreshing, reconnecting, buffering, reaching, hoping, needing. In that moment, Zuckerberg’s past is the film’s present and the future we now inhabit. The laptop isn’t gone, but it’s sitting over there on the desk, collecting dust. Now, it’s the tiny computer in our pocket – the chase is the same.

In the smartphone era, cinema has struggled to keep up. Theatres struggle to draw crowds away from their comfortable couches and streaming apps. Some theatregoers increasingly confuse the moviehouse for their living rooms, indiscriminately texting and playing games during the film. Everything old is new again, of course. Cinema has been here before, with radio in the 1930s, television in the 1950s, and home video in the 1980s.

But as much as it may recall the technological revolutions of days gone by, this moment is undeniably different. None of those earlier competitors had so radically redefined who we are and how we live. Smartphones occupy every waking moment of our existence. The first thing we do when we wake up is check them, and the last thing we do before we go to bed is check them. If watching films is like dreaming, then so too do we bookend our cinematic dreams with the same ritual – glance at the phone one last time before the lights go down, and then rush to see what we missed once the credits roll.

And this is one of modern cinema’s great challenges – how to capture the experience of living a new, smartphone-infused life on screen. This has long been the intentional and unintentional purview of science fiction. The astronauts in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey view a news program on a device that looks remarkably like an iPad, an effect the 1968 production team accomplished through use of an old Hollywood technique, rear projection.

In 1986, James Cameron’s Aliens featured a FaceTime call between heroine Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) and corporate stooge Carter Burke (Paul Reiser), not through a smartphone, but over computer screen teleconference. In each of these scenes, the banality of communication dominates the characters’ behavior. Kubrick’s astronauts absentmindedly chew their space food while watching, and the call between Ripley and Burke is quotidian. These are visions of life infused with technology so thoroughly that it has ceased to be a wonder. Though modern science fiction continues to reach forward into virtual reality and its representation of the digitally enhanced universe through CGI, it is these examples from bygone eras that most resonate with the everyday reality of the devices in our hands.

Praxis

Outside of the galaxy far, far away, filmmakers of numerous genres must devise ways to represent who we are when we’re at home. This is no small task when who we are is changing so radically. In Noah Baumbach’s The Meyerowitz Stories: New And Selected (2017), Danny (Adam Sandler) sits on a couch, texting with his daughter Eliza (Grace Van Patten). He sends her a message, and Baumbach cuts to Danny’s point of view, looking down at the phone in his hand. He shows us the screen, the gray ellipsis that indicates Eliza is typing. Baumbach holds on the shot until the ellipsis goes away, and then a few seconds after that, he cuts to Danny, who looks disappointed. Eliza has intended to reply, and reconsidered. The connection between father and daughter, already tenuous in the film, is eroding further. The humanity at the core of this small interaction speaks to the feeling all of us have when texting with someone else – the uncertainty of their circumstances, hidden from us by the unbridgeable distance between here and there.

On this end of the spectrum, Baumbach finds a realistic way to render his character’s experience of the smartphone, placing the emphasis firmly on the subjective possibility of the camera. It can show us what Danny sees, just as Alfred Hitchc*ck shows the audience what Scotty Ferguson (Jimmy Stewart) sees when he follows Madeline Elster (Kim Novak) through the streets of San Francisco in Vertigo (1957). But filmmakers today also lean towards more ostentatious adoption of smartphone life, as Hitchc*ck does when he shows the audience what L.B. Jeffries (Jimmy Stewart again) sees through the binoculars in Rear Window (1954).

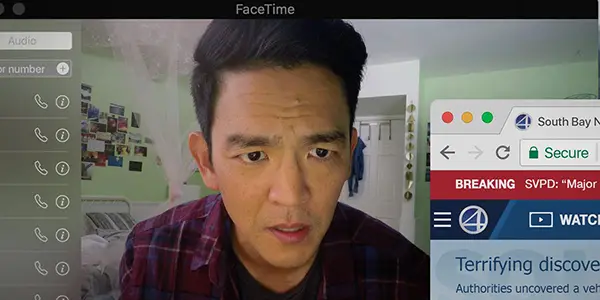

The difference is the mediated experience offered by the device – Scotty’s naked eye versus L.B.’s spyglass. Not much more than a hop, skip, and a jump from the black eyed-binocular rings is this fall’s Searching (Dir. Aneesh Chaganty), an on-screen experience applied to the missing-daughter thriller genre, entirely told through the electronic devices that govern our lives. There are Google searches, two-party FaceTime conversations, YouTube videos, all stretched across fifty feet on the multiplex screen. John Cho, playing the bereft and determined father, does most of his searching from his desktop, a far cry from John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards and the expanses of Monument Valley. His cleverness in deducing how to crack his missing daughter’s password plays as the discovery of a crucial clue, and the film shows every click, keystroke, and login.

In this style of film, which also includes the horror film Unfriended (2014) and its sequel, Unfriended: Dark Web (2018), the diegesis is all. A close cousin to the found footage conceit, the internal logic of these films starts to wobble when they have to stretch to climactic moments. Even more so than in found footage films, the question of spectatorship confounds. While it is clear who is driving the narrative action when Cho’s David is texting with his daughter prior to her vanishing, it is less so when a local news broadcasts airs press conference footage at which David is present. The diegetic experience must dominate so fully that even the inclusion of musical score seems like a cheat, raising audience awareness of the artificiality of the narrative circumstances and distancing them from the intended immersive effect.

Immersion

The cinema’s incredible capability for switching subjectivities even within a single narrative moment seems incompatible with such a limiting experience of storytelling. Inevitably, filmmakers chafe against the box they’ve built for themselves. Even extending the most charitable interpretation of such digitally immersive movies as Searching, thinking of it beyond a gimmick, something about the idea feels hollow. Searching and other films like it assume an entirely connected existence, when all of life is lived through mediated experience. But this is false – as much as it might feel like it, we are not totally connected, and not all of the time. Instead, it feels more like the way we live now is in perpetual simultaneity.

We are here, in the present moment, but we are also there, in some imagined other place. We sit across from someone at dinner in a restaurant, carrying on a conversation about the service, but we also sit in a cubicle at work, responding to urgent after-hours emails. We tell our loved ones about our day and see their non-verbal cues, when they get bored with our stories, when they start to lose interest. But, we also answer texts from friends about weekend plans or who’s going to buy the tickets. These are not discrete parts of our everyday lives, separated by to-do lists, but one collected mishmash of things we are doing now.

Cinema in the smartphone era often strives to achieve this simultaneity in the mundane, everyday exchanges characters have with one another. In a mid-series episode of Steven Soderbergh’s puzzle box mystery show Mosaic (2018) for HBO, a pair of characters sit at a bar. One, Petra (Jennifer Ferrin), is the sister of a man she believes wrongly convicted of a murder. The other, Joel (Garrett Hedlund), is a man Petra believes may know more about the murder than he is letting on. In this moment, and throughout the series, Soderbergh emphasizes the disconnect between who people are when they speak to each other in person and who they are when they text. He uses an extra-diegetic element, the on-screen text message, to illustrate Joel’s dishonesty.

To Petra, he is polite and relatively forthcoming. To his wife, via text message, he complains about having to be in the bar with Petra at all. As the audience members decide who is lying and who isn’t in this whodunit story structure, the contrastive messages communicated by Joel’s body language and dialogue on the one hand, and his text messages on the other, highlight the relative untruth of both signals. He could be lying to Petra, or he could be lying to his wife. The rendering of the message itself is relatively unadorned – it is simple, white text on the screen, not dissimilar from an expositional time-stamp or a flash of subtitle.

Other films attempt to use the screen itself to render a visual approximation of the experience of receiving and sending text messages through superimposition. A step up from the subtitled simplicity of Soderbergh’s Mosaic, Jaume-Collet Serra’s Non-Stop (2014), one of his action collaborations with actor Liam Neeson, adds a floating green box, the text inside. Its intrusion into the film’s shots, complete with a time stamp, adds a ticking-clock element to the narrative, already built on a story dependent on the preciousness of time. Air Marshal Bill Marks (Neeson) receives a message from an anonymous on-board terrorist, threatening to kill a passenger every twenty minutes unless he receives ransom payment. The very possibility of text communication preserves the terrorist’s anonymity for most of the film’s running time.

A cellphone of even ten years prior would have been less effective as a narrative device, because its texting capabilities would have been less ubiquitous. Again, in this scenario, the texts create disconnect between Marks’s in-person interactions and those he conducts over text message. The result heightens the rest of the passengers’ suspicions of him as it becomes clear that the terrorist is framing him for the crime. The texts, their green background recalling the ransom money about to change hands, interrupt the narrative flow in a way that builds suspense, drifting on screen with a pleasant-sounding chime.

Quotidian

But there is also the way in which the smartphone acts as a gateway to other worlds beyond our own, not just a device for person-to-person communication. In Bo Burnham’s Eighth Grade (2018), thirteen-year-old Kayla (Elsie Fisher) lies in bed at night, when she is supposed to be sleeping, and crosses the virtual threshold into a whirlwind of Instagram photos, tweets, and Snapchats. Burnham scores the scene with Enya’s “Orinoco Flow,” a needle-drop that urges Kayla to “sail away, sail away, sail away” in its chorus. Sail away she does, liking, favoriting, and sharing what she sees in the swirling maelstrom of #content from friends, strangers, and brands. She goes everywhere without going anywhere, a perfect encapsulation of our modern, bifurcated existence. Burnham’s edits match the pace, his rapid cuts between Kayla’s face illuminated by the screen’s glow and the mediated social life she desperately craves. At the end of the montage, it’s unclear how much time has passed. It’s a drunken debauch without a drop of drink. It’s a dramatic dream without a second of sleep.

As much as smartphones may be driving us to distraction, dependence, and division, they are an essential part of our modern lives. To see cinema grapple with how to represent their importance on screen is vastly more interesting than common uses of CGI, even with the latter’s ability to create worlds, monsters, and heroes heretofore thought impossible to visualize. Phones, for good and ill, are inextricable artifacts of real life, but they are also doors to fantasy worlds. They offer us ordinary people the chance to mediate ourselves by creating an ideal self that we show to others, no matter how different that self may be from who we see in the bedroom mirror. As we struggle to figure out how smartphones are changing us, their cinematic representation may help us forestall our own device-induced doom. Films are mirrors. Seeing ourselves using smartphones in cinema may stop that mirror from looking quite so black.

What are the most effective examples of smartphone use in cinema to date?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Brian Brems is an Associate Professor of English and Film at the College of DuPage, a large two-year institution located in the western Chicago suburbs. He has a Master's Degree from Northern Illinois University in English with a Film & Literature concentration. He has a wife, Genna, and two dogs, Bowie and Iggy.