Bigotry And Hypocrisy In John Abraham’s DONKEY IN A BRAHMIN VILLAGE

A writer from Mumbai, India

Indian avant-garde filmmaker John Abraham‘s 1977 black and white film Donkey in a Brahmin Village (Tamil: Agraharathil Kazhuthai) opens with Tamil poet Subramania Bharati‘s poem in praise of fire, recited fiercely by a gravelly male voice. It is only towards the end of the film when this poem is recited again by the narrator that we realize its relevance to the screenplay. In between the two recitals, a series of unjust events shape the film’s narrative and form the fuel for igniting a climatic revolutionary fire.

In a short career brought to an abrupt end due to his accidental death in 1987, Abraham defied conventions – be it the controversial subjects he explored in his storytelling or the nonchalant irreverence towards filmmaking norms in general. For him, the ideas and themes that he wished to communicate took precedence over the technical aspects of his films. Having been mentored and influenced by stalwarts of Indian cinema like Ritwik Ghatak and Mani Kaul, the maverick Abraham trod his own path and expressed his unique perspective of life through his four feature-films that remain incomparable to this day.

Those familiar with Abraham’s small but exemplary body of work would be aware of his tit-for-tat philosophy against injustice. A common thread running through his filmography is the attempt to awaken the collective conscience of viewers against man-made systems that perpetuate and normalize oppression of the weak. Often labeled a Marxist for addressing the concerns of the marginalized, Abraham shunned the idea of categorization and saw himself as a humanist. By spotlighting the fascist structure of human thought and the cruelty it inflicts upon innocent beings, his cinematic preoccupation bears resemblance to that of Robert Bresson. But where he finds himself poles apart from Bresson and more on the same footing as Sergei Eisenstein, is the approach of his protagonists in dealing with suppression and discrimination. Unlike Bresson’s characters who succumb to their fate of suffering, Abraham’s characters revolt against the stranglehold of authority, provoking his audience to seek liberation in their lives.

Double Standards of Society

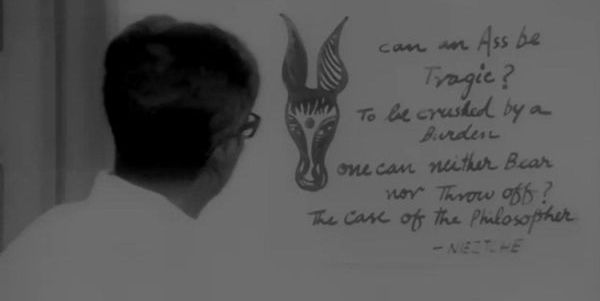

Inspired by Bresson‘s Au Hasard Balthazar (1966), at the heart of Donkey in a Brahmin Village is a little donkey whose mother is killed by a frenzied mob in the city of Chennai, Tamil Nadu. The donkey accidentally finds its way to the house of Narayanaswamy (M. B. Sreenivasan, who doubles as the film’s music composer), a professor of Philosophy in a leading college. On learning from a neighboring boy about the tragic end met by the donkey’s mother, Narayanaswamy takes the animal home as a pet. What follows is Abraham‘s exploration of bigotry, class discrimination, moral hypocrisy, and sadism in human nature.

In the social hierarchy of domesticated animals, donkeys are placed by humans on the lower rungs. Their treatment parallels that of the lower-caste or ‘untouchable’ members of Indian society. We witness this discrimination for the first time when Narayanaswamy requests that his house-maid clean the poop of Chinna (lovingly called ‘little one’ by him). She refuses to clean the donkey’s mess, even for extra pay. Had it been a dog or a cow, she would not have objected. Even the mischievous students of his college are contemptuous of the donkey and mock their professor by playing pranks. The college principal requests him to ‘do something’ about the donkey as it is demoralizing to the institution. Having no alternative, he is compelled to take Chinna to his village and leave it there with his parents.

The real trouble for the donkey begins after reaching Narayanaswamy’s village of predominantly upper-caste members of the Hindu religion – known as Brahmins. Chinna immediately becomes the object of contempt for the Brahmin villagers who consider donkeys a ‘pollutant’ and a threat to their religious purity. Unlike cows, regarded by Hindus as sacred, donkeys are subjected to physical abuse and overburdened with harsh labor. This oppression and domination are justified by the moral custodians of religion as donkeys and Dalits (the lower-caste human beings) are termed ‘impure’ and deserving of the harsh treatment meted out to them, for they likely sinned in their past lives.

On close examination of the structure of human civilization, it would be safe to infer that hegemony isn’t simply a problem of religion or caste. The rot runs deep within human nature. Our much-cherished education system that churns out a white-collar workforce for the business world is merely a sophisticated replacement of the ancient religious system. The ‘uneducated’ lot are relegated to blue-collar jobs and lower social standing unless they climb the ladder through entrepreneurial means. In Donkey in a Brahmin Village, the donkey serves as a metaphor for all unfortunate beings that find themselves on the fringes of society’s accepted norms.

Subjugation of the Weak

One of the more interesting and satirical sequences in the film finds Narayanaswamy returning to his village after a few months and listening to his father recount complaints by a few Brahmin villagers about Chinna’s alleged misdeeds. We learn that a group of young boys who used Chinna as a scapegoat were behind the mishaps experienced by the villagers. Abraham also breaks through the façade of kinship among the Brahmin community by exposing their jealous nature towards members of their clan. In one such incident, an elderly Brahmin – aided by one of the boys – drops Chinna off at another Brahmin’s house where a potential bridegroom and his family have come to see his daughter. The visitors feel insulted by the donkey’s presence, and leave fuming.

In between the montages of these anecdotes, Abraham interestingly intersperses one particular shot repetitively. After every act of injustice against Chinna, the film cuts to a scene of Chinna and its custodian, the mute Uma (Swathi), passing across the frame with Narayanaswamy and his father seated in the background. This is followed by Uma walking alone in the village and being hit on by a working-class villager. A vulnerable Uma eventually gives in to the man’s advances and later gets pregnant with his child. Through the juxtaposition of two defenseless beings who have no control over their situation, Abraham draws parallels between the helplessness of weak and voiceless species in a brutal world.

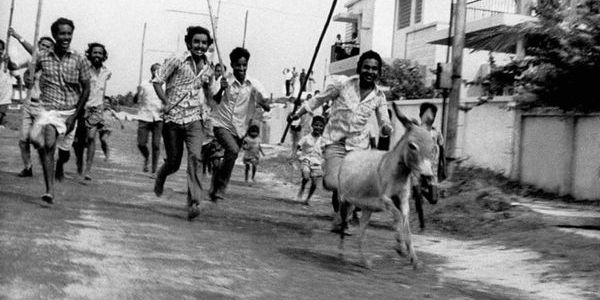

The donkey’s aggravating predicament reaches a tipping point when Brahmin priests discover Uma’s stillborn child at the village temple’s entrance; the blame for which is pinned on Chinna. The orthodox priests interpret it as a bad omen and assign to a group of workers the task of ending Chinna’s life. In the following scene where the workers take Chinna to a pit and beat it to death, the narrator’s thunderous voice erupts again to recite more of Subramania Bharati. The words run in diametric opposition to the visuals on screen as Bharati draws verses from holy scriptures of the Hindus, describing the presence of God in each atom of every living and non-living being. Through this impactful scene, Abraham goes on a frontal attack against the bigotry and hypocrisy of upper-caste egoists. Since time immemorial, the priests who projected themselves as figures of authority on religion, have selectively used only those verses from ancient scriptures that served their agenda of controlling the masses. The verses having the potential to jeopardize their nefarious schemes were conveniently discarded or overlooked by the clergy.

Revolution Triggered

Later in the film, the Brahmins are haunted by guilt and begin to repent for their ghastly act. Soon, a few of them begin to spot living manifestations of Chinna. Miracles occur in the ‘elite’ village: an 80-year-old paralytic woman is able to walk again, and the long-lost son of the village chieftain returns after years. The same Brahmin priesthood that previously saw the donkey as a ‘pollutant’ develops a high reverence for Chinna. They even decide to construct a temple in its honor. On returning to the village again after a few months, Narayanaswamy learns about the tragic fate of Uma’s stillborn child and that of Chinna. From here on, Abraham deviates from Bresson’s path and carves his own way.

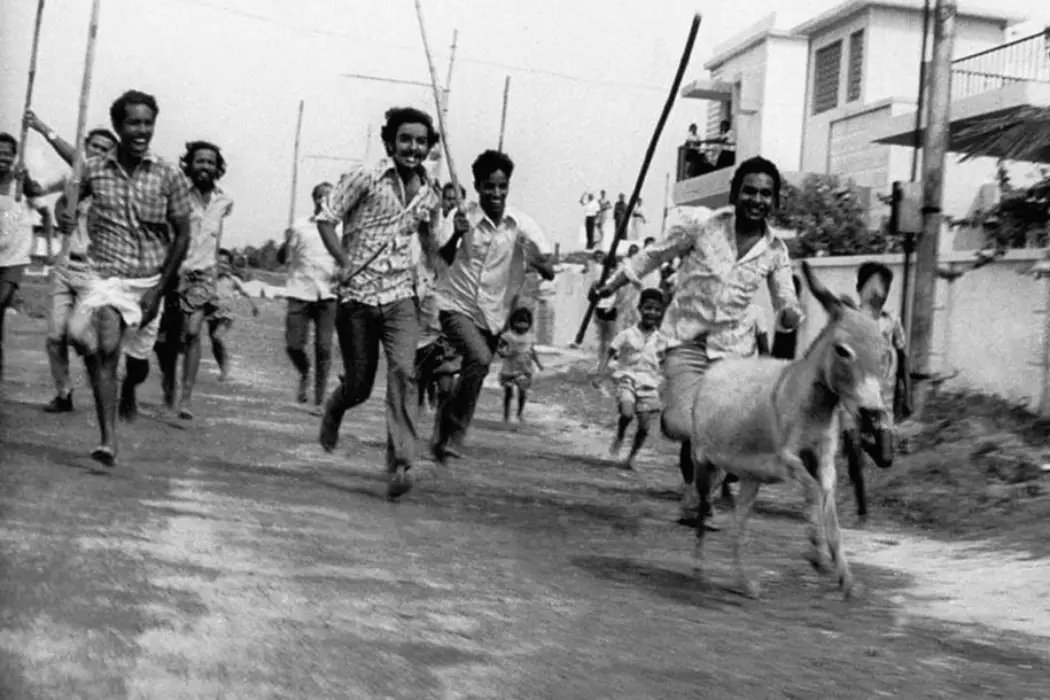

Unlike the protagonists of Au Hasard Balthazar, who passively endure cruelty, Abraham’s characters decide to fight back. The narrator joins in with Bharati’s revolutionary poem “Dance of Doom” echoing the thoughts of Narayanaswamy, who is immersed in reading a book. On his bed, sits another book that is adorned with Che Guevara‘s face. Abraham sets the tone for what is to come. Years later in his final and most-acclaimed film Amma Ariyan (1986), he would again use revolutionary art and Marxist icons. Images of Che seep into it as well, but the poetry of Bharati gives way to Pablo Neruda’s “Nothing but Death”. The rebellion in Donkey in a Brahmin Village erupts during the climax sequence in which a fire is lit and spread across the village to avenge the injustice against Chinna. Abraham hopes that the corresponding fiery poem of Bharati will ignite a revolutionary fire within us too.

Conclusion

Donkey in a Brahmin Village is deserving of its cult status in Indian cinema as it dared to expose the hideous aspects of religion and society that tend to be overlooked or brushed under the carpet. Sidestepping some of the production foibles that Abraham couldn’t care less for, his film has the courage to suggest a way forward, instead of leaving the viewer with unanswered questions. The unique voice of John Abraham and his distinctive style of filmmaking makes it a worthy watch for lovers of world cinema.

What are your favorite films with revolutionary overtones? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.