The Beginner’s Guide: Stuart Gordon, Director

John Stanford Owen received his MFA from Southern Illinois University,…

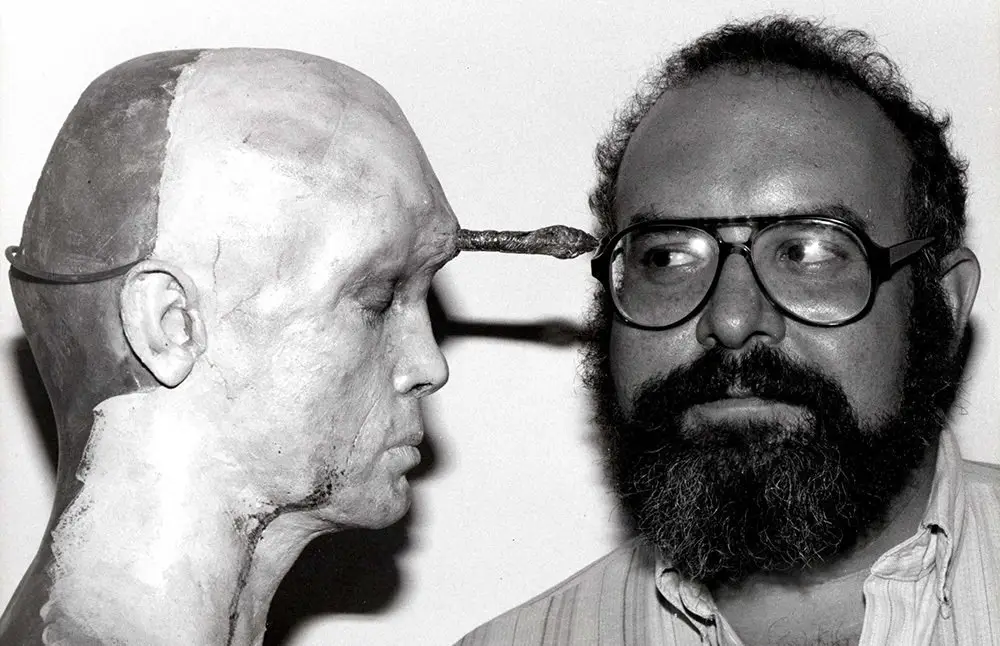

To illustrate the world’s absurdity, Stuart Gordon relies on blatant symbolism, including but not limited to viscera tumbling from opened bellies and endocrine glands erupting from foreheads. In this way, the director holds our latent anxieties up to the light like a color slide, feeding our strangest and most secret thoughts into a celluloid projector. While that shtick sounds sadistic by design, each title in his cinematic library skews more therapeutic than exploitative.

With a few exceptions in the latter portion of his career, the films’ camp factor stays cranked to a high volume, a purposeful manoeuvre leveraged to expose one insanity or another. In other words, the silliness functions as a vehicle for the exploration and understanding of life’s inherent turmoil. In a sense, Gordon plays the double role of Freudian psychologist and benevolent comedian, delivering self-aware horror flicks wherein the image of a severed head smashed against a wall produces giggles over shrieks.

Therein lies his pièce de résistance: while the movies’ kooky sideshows unravel, we laugh in self-defense. This technique finds roots in dramatic/literary traditions, which means these films share an unbreakable connection with the fore-mothers and fathers of horror. In that regard, the director tackles the genre in a manner befitting authors the likes of Mary Shelley, Bram Stoker, Edgar Allan Poe, and Ira Levin. And of course, if you ask fans about which author holds the most prominent spot in this storyteller family tree, you hear the name H.P. Lovecraft before all others.

No question that grindhouse connoisseurs revere Gordon as a B-movie sultan. To that end, his connection with prominent names in classic literature stands not in contrast, but wholly in sync, with his status as a cinematic goofball. The aforementioned writers sought to prepare the public to deal with issues, a narrative goal the director holds dear. To get concrete, if Frankenstein metaphorized the Industrial Revolution and Dracula represented the syphilis outbreak spread across Victorian England, then Gordon’s films also aim to enlighten and prepare audiences for inevitable craziness.

For a prime example of storytelling as a moral responsibility, look no further than From Beyond, Castle Freak, and Re-Animator. Before lighting up our screens, these titles began in pages penned by Howard Phillips Lovecraft, an author who asked readers to assuage the notion of understanding our turbulent circumstances. Instead of finding meaning in chaos, Lovecraft’s tales encourage acceptance of all the madness. In fact, the narrative goal hinges not so much on coming to terms with universal illogicality, but an out-and-out celebration of it. With a bevy of loose Lovecraft screen adaptations comprising Gordon’s body of work, it becomes clear that the author unearthed the embrace-the-weird notion and the filmmaker championed it.

A Brief Bio: Stuart Gordon and the Nude Peter Pan Fiasco

While ‘nude Peter Pan fiasco’ makes for a stellar band name, those words describe events leading to Stuart Gordon’s arrest. His brush with law enforcement stands out in the filmmaker’s biography, not due to the sensational nature of the anecdote, but because it exemplifies the resonant material he went on to create. Starting with his early theatre work, it becomes clear that Gordon’s scripts lean heavy on reinvention, as if to remind us that only so many stories exist, but originality remains endless.

As the founder of both the Screw and Organic Theatres, he leveraged that reality while producing over three dozen plays that adapted and reintroduced classic favorites such as George Orwell’s Animal Farm and Kurt Vonnegut’s Sirens of Titan. Many of these performances came with twists that spotlighted not only directorial flair, but also enhanced and expanded the social relevance of older works. Ergo, the plays Gordon put on underwent updates to reflect the current cultural zeitgeist.

Born from the social unrest happening in the U.S. during the Vietnam War, the re-purposed Peter Pan stood out among these evolved adaptations. During his time at the University of Wisconsin, Gordon participated in the tumultuous antiwar protest that took place outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention. As police swung their batons, pepper spray misted the air, and bodies fell to the asphalt, organized civil disobedience turned to a flurry of violence, a bloody event that inspired Gordon’s updated rendition of the J.M. Barrie story about never growing up.

Not a word of dialogue or plot structure changed, however Peter and the Lost Boys became peaceniks; the Darling siblings took the stage as straight-edged suburbanites; the pirates went from swindling seafarers to the Chicago city police; and Tinkerbell’s fairy dust turned to psychedelic drugs. After Gordon included a light show that scrolled across the bodies of seven nude dancers, he and his wife Carolyn Purdy (who played one of the clothing-optional performers) went into police custody.

Listening to the quiet, measured Stuart Gordon give interviews, this story feels as if it lives at the bottom of the c*cktail story reservoir, no matter the edgy street cred it produces. Seldom mentioning himself, the director seems more prone to discuss interesting set stories and to praise his actors’ performances. But the anecdote warrants mention as it represents the daring of his work. His inaugural motion picture, Re-Animator, set the precedent for a plethora of subversive art that mirrors the risque rendition of Peter Pan.

Re-Animator (1985)

With the release of his debut picture, the first of several Lovecraft screen adaptations, Gordon established himself as an audacious filmmaker. Following the misadventures of a mad scientist with a myopic dream of eliminating death itself, the movie delights with a story surrounding Herbert West and his neon-glowing serum that causes corpses to rise and go berserk. Not straying far from the hamminess of his theatrical roots, Re-Animator established the director as an auteur of horror/comedy hybrids.

Where genre mashups often drown under the weight of their own conventions, this film rejects several horror platitudes that otherwise defined 1980’s slasher pictures. To get specific, sex never equates death, the bookish, awkward fellow tackles the lead role, and most every character makes the most intelligent decisions given their circumstances. With those factors at play, the film gained the admiration of critics and audiences, earning a spot among celebrated horror cinema the likes of The Shining and The Wicker Man (1973).

With the milestone of Re-Animator, horror fandom also gained a new acting troupe, namely Barbara Crampton and Jeffery Combs, fearless performers who starred in many of Gordon’s most beloved works throughout the next years. Not many actors deliver such dialogue with a straight face, and yet Combs manages the line “who’s going to believe a talking head?,” with a deadpan, un-crackable expression. In the end, acting case studies like this one heighten Re-Animator’s social significance.

Our anti-hero acts with a cold indifference to death, not moving beyond the matter-of-fact clinicality of it all. His face never so much as twitches when the body parts begin flying, and that happens in light of how far removed that character stays from emotional reality. See today’s headlines scroll beneath the cable news talking heads, and as the darkest timeline becomes more real each day, notice how we share many similarities with Herbert West. It matters that the movie produces laughter over introspection and self-judgement. The director makes us lower our defenses and, as we chuckle at the silliness, the scariest issues become less threatening.

From Beyond (1986)

What happens when biological urges transform into an unsatisfiable addiction, a magnetic draw so powerful that all inhibition falls to the wayside? The director’s sophomore release answers that question. Whereas Jeffery Combs’ poker-faced acting facilitated Re-Animator’s success as a horror/comedy hybrid, Barbara Crampton wields the dramatic chops in From Beyond. In moving from an idealistic college student to a psychologist who undergoes brain torture, the actress proves not only her versatility but sheer fearlessness. The final girl trope made famous in other slashers released circa 1986 came to a halt with this performance.

Her character, the psychiatrist Dr. Katherine McMichaels, seeks to discover if schizophrenia happens as a side-effect to an overactive pineal gland. The size of a rice grain and located in the brain’s spongy center, that tiny hormone regulator drives a number of philosophical, psychological, and biological debates, including whether or not it enables extended vision into alternate universes. Serendipitous to her thirst for knowledge, Dr. Edward Pretorius, a scientist and BDSM enthusiast played by Ted Sorel, developed a resonator machine that enlarges and revs up the function of that minuscule sliver in the brain.

As the film points out, René Descartes considered the pineal gland the human soul’s home, dubbing it the “third eye” as a moniker that describes a sixth sense. Of course, 17th Century philosophers and discussions over heightened brain activity seem a bit dry for your average exploitation film. But, as the master of reinvention, Stuart Gordon took these concepts and made them the driving force behind a kaleidoscopic movie. The machine enables characters to peer inside another dimension, but in so doing, fanged worms gnaw off heads and exposure to energy fields shackle people with uncontrollable urges.

With body horror prosthetics on par with the hyper-realistic ghouls in John Carpenter’s creature feature The Thing, From Beyond uses masterful practical effects to show physical manifestations of the subconscious. The brain thinks nasty thoughts and the body metamorphosizes in response, shapeshifting into various gooey grotesqueries that represent our darkest instincts and predilections. These include pink goop gushing with gleeful abandon and muscles that indent like clay to the touch. In this regard, the film focuses less on the invisible monsters lurking in other dimensions and more on how we behave in the world we actually occupy.

Dolls (1987)

Even though Dolls showcases the most subdued aesthetic in Gordon’s early work, the film still opens with a teddy bear turning into a snarling hell beast that exacts revenge on a girl’s cruel father and stepmother. Of course, the scene takes place inside the child’s imagination, setting the stage for a tale about adults who refuse to believe kids’ stories. The initial chain of events—a stalled car, a vicious storm, refuge in a mansion owned by a toy maker—lead to the dolls coming to life and murdering. The girl reports the killings she sees; the adults scold her for it.

This late eighties saw a parade of films about small inanimate objects that wake up with homicidal intentions. Child’s Play and Puppet Master, which hit theaters in the following two years, lead some audiences to scoff at the insignificant threat level. “Why not kick the damn thing and run?” became the most-asked question. It seems as though Gordon predicted this response, and so the dolls swarm the characters, sticking them with toothpick-length blades in a method parallel to the multiple knife assassination of Caesar.

The director’s need to reinvent and reinvigorate old stories means he also turns clichés on their ears. The Clue-style mansion, the dark and stormy night, the candle-lit aesthetic, the sexually active girls destined to die—all of that held the recipe for a paint-by-numbers horror flick. Instead, he gives us a moral tale about the importance of imagination and the sacred promise that when young people tell us something, we listen.

Castle Freak (1995)

Of all the images associated with fairy tales, the castle delivers the benchmark example. In Castle Freak, we lay our scene inside one of these stone-and-mortar fortresses, but this time whimsy and magic stay out of the fray. Instead, we meet a hunched-over, grey-skinned figure smothered in scabs and lashes.

With no supernatural elements at play, the narrative makes it clear the mute, mangled being reached this point via hatred and abuse—not born a creature, but made one. As it happens most often, fairy tales travel down the Disney assembly line and the machine strips away the grimier narrative elements. But this film, which Gordon made with the slimmest budget of his career, stays true to the messier elements that stray far from the umbrella of family friendliness.

When Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid went through that marketing rinse cycle, Ariel’s story no longer ended with her death and subsequent transformation into sea foam. Ditto Quasimodo, the protagonist from Victor Hugo’s Hunchback of Notre Dame. In the cartoon version, the bellringer finds a society who accepts and embraces him. The novel, on the other hand, ends with him clutching his beloved’s corpse, laying there distraught before starvation ends his life. Needless to say, things get dark in these stories, and Castle Freak provides a chief example of a cinematic fairy tale sans Disneyfication.

Starring Crampton and Combs in another Lovecraft adaptation, this picture strips much of the in-your-face humor away, though the story falls way outside the category of joyless, uber-serious cinema. Instead, Castle Freak teems with enough Freudian psychosexual machinations to populate a few dozen PhD dissertations. To make it clear, the film follows a manacle-shackled victim with mutilated genitals who suffered years of abuse via food deprivation and beatings with a cat-of-nine-tails.

When the titular castle freak finds a way out of his dungeon confinement, he seeks intimacy but fails to see the difference between sex and violence, a tragic misconstruance that leads to, among other atrocities, the literal eating of reproductive organs. At the same time, the film also chronicles a family deep in grief. A drunken car accident took the life of one child and blinded the other, and in the aftermath, mom and dad teeter on the edge of divorce. The contrast between external forces and the bleak reality of sadness creates a delicate balancing act, making us question where the true horror lies. Another way to phrase it: a suicide attempt occurs, and it happens outside, in daylight, and when internal strife grows that urgent, the real antagonist’s identity becomes clear.

Honey, I (Almost) Shrunk the Kids

A mad scientist harboring benevolent but misguided intentions.

An experiment gone awry in the most catastrophic way.

Corporate greed and ownership of production.

The natural world gaining strength and exacting revenge.

Teenagers who risk dying at any instant.

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids includes many foundational elements that constitute a horror film. It surprises most people to learn that Gordon almost sat in the director’s chair. Though extreme stress and illness prevented him from creating a darker version of the family classic, his script became the feature’s backbone. With a smorgasbord of otherworldly imagery—a child swimming in a bowl of cereal, for example—the film’s visuals look like a suburban Dali painting, aesthetic choices that show this movie sprang from Gordon’s imagination.

Final Thoughts: Where Gordon Belongs in Film History

Stuart Gordon makes films that prove exploitation features belong next to arthouse treasures. In fact, the earlier descriptions account for only a palm-sized selection of the director’s work. Other films include Robot Jox that takes place decades after nuclear war redefined how nations fight. Instead of tanks and warheads, countries use giant robots to settle their beefs. Space Truckers follows the story of a transporter who carries shady cargo without asking questions, and when the delivery contents turn out to be deadly robots running amok, hilarity ensues. And lest we forget Dagon, the Lovecraft adaptation about sawtoothed mermaids and other murderous sea monsters.

Now in his seventies, the director’s prolific output slows down. With a catalog of cinema so multidimensional, it feels difficult to pigeonhole a boiled-down legacy. On one hand, Gordon collapses the wall between highbrow, pinky-in-the-air cinema and populist exploitation films designed to thrill. On the other hand, despite his craft as a filmmaker, he empowers his actors to deliver unforgettable performances. Barbara Crampton went from idealistic college student to mad scientist sex addict to grieving parent in the span of three movies, a fearlessness and versatility that lends credence to the exploitation film as a vehicle to explore human psychology.

Stuart Gordon opened that gate. His actors walked through it.

Let us know your favorite Stuart Gordon film in the comments below.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

John Stanford Owen received his MFA from Southern Illinois University, where he also taught English courses. When JSO is not penning reviews and essays on cinema, he's reading and writing poetry, walking with his dog, or dancing to Radiohead.