The Beginner’s Guide: John Ford, Director

Writer, cinephile and Woody Allen apologist (yes, even The Curse…

When asked about who his favourite American directors were, Orson Welles replied: “I prefer the old masters; by which I mean: John Ford, John Ford and John Ford.” Ford is often painted as a contradictory fellow, hard to pin down. But his body of cinematic work – and to him, directing movies was a “job of work” – tells a different story. His films present a cohesive whole, a clear vision of the world with each new film in dialogue with the ones that came before.

But to talk of a vision of the world is maybe too broad; what Ford really did was chronicle the founding of America and the progression of its society. Locating his characters within the context of American history at all times, Ford gave every story he told an extra dimension. His characters weren’t mere individuals as in the films of his fellow studio directors like Howard Hawks, their destinies were tied inextricably to the forward march of an entire nation.

This allowed Ford to explore endless oppositions. Whether it be European vs Indian, brute force vs book learning, East vs West or savagery vs civilisation, a nation-making opposition is at the heart of almost every Ford film. These vying positions overlap and become blurred, but one side will always turn out to be on the right side of history. But to lose in a John Ford film is a noble thing indeed, allowing the director to, at times, directly critique the progression of American society.

The Western genre is the one in which Ford saw the chance to play out these battles and remain commercially viable at the same time. As he so succinctly put it: “My name’s John Ford. I make Westerns.” Most of his films – and some of his very best – were not Westerns though. It didn’t really matter what genre he chose, the themes, ideas and style were consistent. So, let’s start at the beginning.

1914-1927: Heading West, D.W. Griffiths & the Silent Era

Born John Martin Feeney in Portland, Maine on 1st February 1894, it wasn’t until he departed for Hollywood that John Ford became John Ford. The year was 1914 and he was treading the same path set by his brother Francis Ford who was already making a name for himself as an actor and director in Hollywood. With Francis allowing for a point of entry into the industry, John Ford made his most significant early appearance as a Clansman in D.W. Griffiths’ landmark film The Birth of a Nation (1915).

Unfortunately, many of Ford’s early directorial efforts of the silent era are lost, but enough survive to gain some insight into his early development. After working as a prop man and an assistant director, he eventually got the chance to direct a few shorts before moving onto cheap Westerns with Harry Carey in the starring role. His earliest surviving solo directing credit is a Carey Western, Straight Shooting (1917). Carey’s gritty cowboy persona laid the foundations for the roles in Ford Westerns that would later be filled by John Wayne.

The most interesting of Ford‘s early films is Bucking Broadway (1917), and it does exactly what its title suggests. When Cheyenne Harry’s (Harry Carey) romance with a girl on the ranch hits hard times, she leaves for New York with a slimy city man, and he heads after her. This allows Ford to stage his first truly epic scene as Harry and his gang storm the streets of New York on horseback.

In Ford’s films we tend to learn most about what a character is thinking not by what’s said but by how character’s throw glances towards one another. Ford perfected this during the silent era, reaching its pinnacle in the epic Western The Iron Horse (1924). The film concerns the building of the first American transcontinental railroad and a love triangle. This won’t be the last time the director examines love triangles, and it won’t be the last time he uses glances to convey the anguish, jealousy, distrust and longing inherent to the situation.

1928-1938: The Coming of Sound

When Peter Bogdanovich asked John Ford what he felt about the arrival of sound, he replied: “I didn’t feel anything about it – it was just a job of work.” This is a typical Fordian reply to a question he’s not much interested in answering. But he does go on to discuss how the studio fired him and all the other directors and shipped in theatre directors from the East who would be, it was assumed, better at handling dialogue. When that didn’t work out so well, the studios rehired the old hands, including Ford, on better contracts than they had before.

His earliest sound film to survive is The Black Watch (1929), a relatively mundane adventure epic. Many of the films from this period are marked by the lack of interest Ford seems to show in them. Films such as Born Reckless (1930), The Brat (1931) and Four Men and a Prayer (1938) prove that Ford could make films as dull as anyone. His skill with comedy is often the only thing worth mentioning about his worst films of this period. His very worst film of the decade was Mary of Scotland (1936), with Katherine Hepburn as Mary. Confined to uninteresting interiors and too reliant on a dull romance, the film holds little interest today.

The three key Ford films of this period are the trilogy of films he made with comedian Will Rogers in the leading role. These films – Doctor Bull (1933), Judge Priest (1934) and Steamboat Round the Bend (1935) – approach, with humour, small-town Southern Americana towards the end of the 19th century. Ford’s interest in the underdog and ordinary, simple folk, and where they stand within the context of America, is brought to the fore. In Judge Priest, Will Rogers’ priest fights his battles for justice and equality through the court over which he presides.

The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936) would approach similar themes from a different angle. It tells the (loosely) true story of Dr Samuel Mudd, the man persecuted for treating the injured John Wilkes Booth hours after he assassinated Abraham Lincoln. The director shows how justice is something that has to be fought for, especially when the established institutions are uninterested in it. Ford, whose parents were Irish immigrants, also approached the issue of Irish occupation and independence in The Plough and the Stars (1936) and The Informer (1938).

1939-1941: Three Years that Made John Ford

1939 has long been talked about as the greatest year in the history of American movie-making. In some senses that’s justified – the three films made by John Ford that year justify it by themselves. But the films we tend to associate with this most vaunted of calendar years are Gone with the Wind, The Wizard of Oz and Mr Smith Goes to Washington. Not one can match Ford’s three: Stagecoach, Young Mr Lincoln and Drums Along the Mohawk.

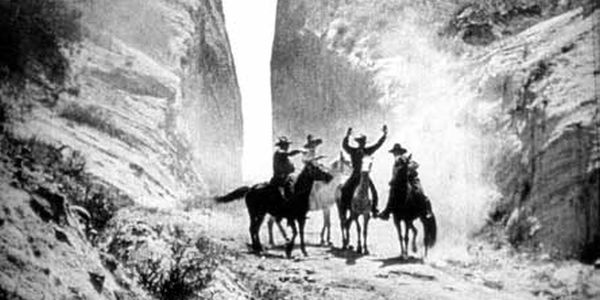

Stagecoach is Ford’s first masterpiece, his first Western of the sound era and John Wayne’s first starring role in an A-picture. Conventional thought tends to view it as an early, safe Western, but this is far from true. Ford’s eye for an epic composition was let loose on Monument Valley for the first time, throwing the cast of underdog, misfit characters into contrast with the vast natural landscape. It’s a film about bad men who turn out to be good and reputable men who turn out to be crooks.

It’s not Wayne’s jailbreak cowboy who’s put in cuffs at the climax, it’s the suited banker whose sinister proclamations resonate eerily with our 21st century predicament: “America for Americans! The government must not interfere with business! Reduce Taxes! Our national debt is something shocking! … What this country needs is a businessman for president!” There is an element of caricature in this portrait; still reeling from the Great Depression, bankers were not thought of kindly then, as they’re not now.

The way Stagecoach subverts conventions while sticking to them, presents images that could only ever have been composed by Ford and also stages the greatest Indian vs American chase in history marks this film out as a landmark for Ford.

Young Mr Lincoln takes the myth and the legend that surrounds Abraham Lincoln and throws it to the wind. Instead, we get Henry Fonda playing him as a small-town lawyer striving for justice and equality through the courts as Ford’s Judge Priest did before. The Great Emancipator he may be, but Lincoln never steps foot in Washington during the film; he’s a penniless man who rides a mule that’s plainly too small for him, his legs nearly reaching the floor. To Ford, Lincoln is just another ordinary man caught up, in his own way, in the inevitable progression of American society.

Drums Along the Mohawk skips back in time, and its characters are caught up in the Revolutionary War of 1776. It completes a trilogy of films that year which celebrate the vitality of the underdog and the making of the modern nation. Perhaps not as strong as the previous two, but it’s more than worth seeing just for the ceremonial raising of the first American flag at the film’s climax; Claudette Colbert’s reaction: “it’s a pretty flag, isn’t it?”

1940 saw the release of two more films by John Ford: The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home. The Grapes of Wrath, adapted from the Steinbeck novel, follows the declining fortunes of a Midwestern family made homeless during the Great Depression. Yet another underdog tale, winning Ford his second Oscar for directing. In The Long Voyage Home, the characters live together on a ship as Ford’s camera heightens the sense of claustrophobia.

In 1941, Ford returned to small-town Americana with Tobacco Road. It’s a strange and unexpectedly subversive film, ripe with vulgar characterisations of the local people who refuse to give up on the land they live on. Ford’s major film of 1941 was How Green Was My Valley, a cross-generational study of a Welsh mining village coming to terms with rapid social change. Even when Ford locates his films in Wales or Ireland, America is always in the frame. Here, the sons who see no future for themselves in their mining community head off for the promised land of America. This journey across the Atlantic is spoken of around the family table in near biblical proportions.

These three years helped cement Ford’s themes, style and preoccupations. It was a productive period brought to an abrupt end by the Second World War.

1942-1945: The War Years

In 1942, 43 and 44, Ford was unable to make any commercial films as he was serving in the United States Navy. In his role as head of the photographic unit for the Office of Strategic Services, he made several documentary films and instructional films that were screened to serving men. The documentary images he captured in The Battle of Midway (1942) and December 7th (1943) are simply astounding.

Armed with a small 16mm camera, Ford put his life at risk to capture on film the Battle of Midway in the Pacific as the US forces battled the Japanese in the sea and in the air. On the other end of the spectrum was Sex Hygiene (1942), which does exactly what it says on the tin. To discourage the recruits from having sex, the film showed what kind of mutilated forms the men’s genitals could end up in if they caught any STDs.

When he did return to commercial film-making, it was with a war film, They Were Expendable (1945). It’s telling that Ford chose to dramatise the story of America’s single biggest defeat during the war. There’s no glorious success at the end; America lost the Philippines to the Japanese. Instead, the film chronicles the heroic last stand, men fighting on even once defeat was inevitable. That’s glory enough for Ford.

1946-1950: A Return to the Western

Once the war was won, Ford made a swift return to the Western genre, making six of them in the space of five years.

The first was My Darling Clementine (1946). The story is an old one; Wyatt Earp (Henry Fonda) and his brothers arrive in Tombstone, and one of them is killed. Earp becomes Sheriff in order to avenge his brother’s death, clashing with the treacherous Clanton Gang and the ailing Doc Holliday. The showdown at the OK Corral has been adapted countless times, but Ford’s is by far the best. It’s much less interested in the showdown and the violence than in the conversion Earp goes through from vagrancy to civilisation. While the slow death of Doc Holliday signifies the death of a barbarous frontier spirit being replaced by community and civilisation.

Briefly moving away from the Western again, Ford made a self-consciously arthouse film with The Fugitive (1947). Visually striking, but drowning in symbolism, the film proves that Ford was at his best when working within commercial limitations. Aside from the Cavalry trilogy, the other two Westerns from this period were 3 Godfathers (1948) and Wagon Master (1950). The first was a remake of an early silent film Ford had made – Marked Men (1919) – and returns to his old notion of bad men doing good things.

In Wagon Master (1950), we see a society built in miniature. For the group of Mormons to get to where they need to go to, they need the help of a couple of drifting horse traders. Marrying the horse traders’ practical skills together with the will, faith and community of the Mormons, Ford allows a glimpse of how he sees society as being constructed. The streetwise misfits are as vital as the collective strength of the wider community.

Ford’s cavalry trilogy was spread out through this period, consisting of Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949) and Rio Grande (1950). These films weren’t intended as a trilogy, Ford claimed it just happened that way. The US Cavalry were on the front line of the push West, forever at war with understandably hostile Native Americans. They were the forgers of the nation we know today, and the forging wasn’t always pretty.

Fort Apache sees Colonel Thursday (Henry Fonda) push the boundaries and lead his men into a disastrous and bloody battle with the Apaches in pursuit of personal glory. Ford paints Thursday as a monster; he’s hostile, war-mongering and hated by his men. All of these things are thrown in contrast with John Wayne’s dutiful and well-liked Sergeant York. Here, the East is represented by the foolhardy Thursday, while man of the West, York, is the moderate force. Still, when Thursday gets himself and his men killed, Ford insists upon the necessity of the lie as York defends his reputation as a great man of the Cavalry. Ford always insisted that these heroic myths – as untrue as they might be – are necessary for the society to function.

She Wore a Yellow Ribbon strives to tie together the domestic realities of Cavalry life with the dutiful aspects, placing the family in the frame much more firmly than Fort Apache. The vivid colour shots of family life and Monument Valley are what stand out most about this optimistic Cavalry Western though.

And Rio Grande takes the Sergeant York character from Fort Apache, and promotes him to Lieutenant Colonel Kirby Yorke. When his son, Tyree (Ben Johnson), and then his son’s mother, Kathleen (Maureen O’Hara), encroach on his work life in the Cavalry, he must somehow toe the line between duty and family. He’s coming to terms with the domestic while Kathleen must reconcile the savagery she encounters in the West.

The 1950s: The Decade of Major & Minor Masterpieces

Throughout his career, Ford returned time and again to Ireland. In the 50s, he set two of his best films of the decade there: The Quiet Man (1952) and The Rising of the Moon (1957). The former, set in 1920s Ireland, sees John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara develop their most successful rapport as a pair of battling lovers. Wayne‘s Sean Thornton returns to his Irish homeland from America to reclaim the farm he was born on, and that’s where he meets O’Hara‘s Mary Kate. The Rising of the Moon combines the best of comic Ford with his interest in the Irish battle for independence.

What Price Glory (1952) came next. The film was based on a fervently anti-war play, but Ford, with his strong belief in the nobility and camaraderie of warring soldiers, dropped most of the anti-war politics and overloaded it with humour, making for a strange and ultimately unsuccessful war film. The Sun Shines Bright (1953) saw Ford return to the Judge Priest character, this time played by Charles Winninger. With no stars and a small production size, the film is among the director’s most personal. The leisurely pace allows for close examination of Southern communities.

The 50s was a great decade for Ford‘s biopics too. The Long Gray Line (1955) is based on the life story of Marty Maher, a truculent Irish immigrant who spent 50 years at West Point military academy, rising from dishwasher to officer. Undoubtedly another statement in support of the US military tradition, Ford, as in Rio Grande, questions what happens when family domesticity clashes with patriotic duty. The director tackled similar themes in his Spig Wead biopic, The Wings of Eagles (1957). He paints a picture of a man who failed to reconcile duty and family until it was too late.

The most famous film Ford made in the 50s, and perhaps during his entire career, was The Searchers (1957). It’s the film that inspired movies from Star Wars (1977) to Taxi Driver (1976). John Wayne plays the ex-confederate soldier, and now drifter, Ethan Edwards, a man without a place in the world. The Searchers is a film about family, and why Ethan can only ever hover on the peripheries and never be a part of it. He’s the hero and the villain; the saviour and the racist, unstable threat.

Ethan pours himself into the search for his niece who was stolen and raised as an Indian after a tribe of Comanches killed her family. He saves the girl – though he toyed with the idea of killing her instead – and restores a family he has no place in. For all the harsh beauty of the location shots, the camera is often placed within the family home peering through windows and doors – the same door that would slam shut on Ethan at the end of the film as he wandered off to who knows where. Does Ethan refuse to settle because he can’t? Or because he won’t?

The 1960s: A Period of Revisionism

By the 1960s, America, the country whose myths he’d chronicled, was shifting beneath Ford’s feet. This had a clear impact on his film-making, which took a decisive turn towards revisionism during his final decade as a director. Five of the eight films he directed in the 60s were Westerns, demonstrating the fact that he seemed to grow closer to the genre as he grew older. The first of them, Sergeant Rutledge (1960), attempted to approach the neglected role of black people in Western mythology.

Rutledge is accused of raping and murdering a woman and is put on trial in front of a military jury. Where the film falls down is in its lacklustre humour and caricatured roles. Ford certainly was the first director to cast a black hero in a Hollywood Western though, and the fractured flashbacks offer an interesting interpretation of a black man’s experience being accused of the most heinous of crimes by a white world.

Ford claimed to make his next film, Two Rode Together (1961), as a favour to studio head Harry Cohn. A strange Western, starring Richard Widmark and James Stewart, in which every character’s a cynic, and the main stamps of Ford are the attempts at squeezing (weirdly dark) humour out of every scene. It has to be seen purely for its anomalous status in the Ford canon. Off the back of two films that were interesting yet flawed, Ford surprised with his final truly great film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962).

The film asks how myths and histories are created by delivering the whole narrative via flashbacks. In the present, Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart) is attending the funeral of Tom Doniphon (John Wayne); while he’s back in his old town, Stoddard recalls how he came to be known as the man who shot Liberty Valance. It needs to be seen with fresh eyes, so I won’t reveal spoilers. But Liberty Valance stands as Ford’s ultimate declaration on American progress, printing the legend and what’s lost (and won) when civilisation triumphs over the savages and the gunslingers.

Next Ford would tackle a section, alongside Henry Hathaway and George Marshal, of the Western Cinerama epic, How the West Was Won (1962). Ford’s segment concerned the Civil War, the Cinerama experiment wasn’t much of a success though and Ford hated using it. For his final collaboration with John Wayne, the pair headed to Hawaii and made Donovan’s Reef (1963), about a US Navy veteran, Guns Donovan (Wayne), living on the island. Within the framework of a knockabout comedy, Ford manages to challenge themes of racism and American profiteering.

Having already had a crack at revising the position of black people in his films, he would go on to do the same for Native Americans and women in Cheyenne Autumn (1964) and 7 Women (1966) respectively. Unfortunately, both attempts failed to reach the less than giddy heights of Sergeant Rutledge.

If Cheyenne Autumn was a noble yet failed attempt to grant humanity and dignity to the suffering of the Native Americans, 7 Women was a revision that didn’t need to be made. Ford was often accused of sentimentalising his female characters, yet they were often the heroes (usually played by Maureen O’Hara), stoically holding civilisations together and never dispensable in the story he told of America’s birth and ascendancy. 7 Women is most interesting for its revisiting of Ford’s interest in the last stand and the glorious defeat, not its take on womanhood.

To finish with a near impossible question: what is John Ford‘s greatest film for you? And why?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Writer, cinephile and Woody Allen apologist (yes, even The Curse of the Jade Scorpion) from the UK. More of my writing can be found at rgfadein.wordpress.com