The Beginner’s Guide To The Golden Age Of Mexican Cinema

Madeline Hrabik is a writer, film buff, and amateur historian…

When Mexican film is brought up, what comes to mind for many are films such as Amores perros (2000) or Y tú mamá también (2001), maybe the director Guillermo del Toro or actor Gael García Bernal. But there’s much more to Mexican film than that. In fact, many of the greatest Mexican films of all time were made during the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema (the 1930s through late 1950s), an era of timeless stars, legendary directors, and critically-acclaimed film classics.

As opposed to the U.S., the film industry was off to a much shakier start in Mexico, with the early decades of the new medium blighted by limited and uneven funding, stringent censorship, competition with foreign films, and its stars leaving for Hollywood. While there were a handful of successes during the silent era, most notably, El automóvil gris (“The Grey Car”) in 1919, it was not until the 30s that the Mexican film industry began to find its footing, though tentatively.

A number of renowned films were produced during the 30s, including the film ranked by Somos magazine as the greatest Mexican film of all time, Fernando de Fuentes’ Vámonos con Pancho Villa (“Let’s Go with Pancho Villa”) (1936). Gritty and harrowing, the film gives an utterly unromantic take on the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), from which the country was still feeling the aftershocks.

Going into the 40s, the Mexican film industry remained on shaky ground, but then, in 1942, two things happened. One, Mexico’s National Bank and President Miguel Ávila Camacho initiated the Banco Cinematográfico (Cinema Bank) to fund private film producers; and two, the U.S. provided Mexico with raw film and cinematic equipment after Mexico joined the Allies in World War II. As a result, the Mexican film industry was able to enter a new era of stability and success.

This time period, the 40s, shines brighter than any other decade of the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema, with so many films of such great technical and artistic merit. Director Emilio “El Indio” Fernández seemed to be churning out masterpieces like Model Ts: Enamorada (“A Woman in Love”) (1946) and Río Escondido (“Hidden River”) (1948) both received the Ariel Award for Best Picture (the Mexican version of the Academy Award); and María Candelaria (1943) gained international acclaim upon being screened at the Cannes and Locarno film festivals.

The 40s also saw the beloved comic Cantinflas (real name Mario Moreno) in his first full-length feature film, Ahí está el detalle (“There’s the Rub”) (1940), a highlight of his long career. Also worth mentioning is Julio Bracho’s Distinto amanecer (“Another Dawn”) (1943), a film noir style thriller that tackles such themes as political activism and solidarity.

Up until this point, the genres that dominated Mexican cinema were family melodramas, comedies, and comedias rancheras (comedies set on a ranch or small town). But the late 40s brought a new genre, the cabaretera film. Cabaretera means cabaret dancer, aka a vedette. Set in night clubs, these films starred the vedette herself, who was thrust into an urban world of crime and sexuality as a result of some personal misfortune. The genre is also characterized by extravagant costumes, flamboyant dance numbers, and Afro-Cuban music – the danzón, the mambo, the cha-cha-chá, etc.

The cabaretera genre continued into the 50s, at the same time that the legendary Luis Buñuel, who had made two underwhelming films in Mexico in the 40s, got his groove back with the brilliant Los olvidados (“The Young and the Damned”), a gritty, sharp film about urban youth in Mexico City. Besides a few stand-out cabaretera films, it was really Buñuel alone that made Mexican cinema shine throughout the 50s, with such great films as Subida al cielo (“Ascent to Heaven”) (1952), Ensayo de un crimen (“The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz”) (1955), and Nazarín (1959).

Yet, as the 50s went on, the film industry stagnated. Unionization had kept fresh, new talent out of the industry, and the films being produced were tired, formulaic. One of the biggest stars of the era, Pedro Infante, died in a plane crash in 1957. After Simón del desierto (“Simon of the Desert”) in 1965, Luis Buñuel headed back to Europe to make films. The Ariel Awards ceremonies were halted in 1958 because so few films were being made. They weren’t reinstated until 1972, and it wasn’t until the early 90s that Mexican film was revitalized.

But the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema left us with some real gems that are more than worth a watch, especially if you already love classic film. I’ve selected five films that demonstrate the excellence of the Golden Age while at the same time being accessible to someone unfamiliar with this era of film.

Enamorada (1946) – Emilio Fernández

Initially I wasn’t sure about including this film, as it’s pretty significantly rooted in the context of the Mexican Revolution, but the ideals of the revolution as expressed in this movie – redistribution of wealth, toppling the 1% – are still hugely applicable to the modern world. And since Enamorada is such a great movie, I couldn’t not include it.

Inspired by Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, Enamorada tells the story of the revolutionary General José Juan Reyes (Pedro Armendáriz) taking over the town of Cholula, where he falls in love with Beatriz Peñafiel, daughter of one of the town’s wealthiest men. Beatriz, who could be played by none other than María Félix, is one of the fiercest, most fiery female characters ever to grace the silver screen. Her death glare is truly fatal.

Despite its name, Enamorada is so much more than just a love story – it’s a drama with a bit of comedy thrown in, engaging deeply with such themes as class, religion, idealism, nationality, and gender. Every role is fantastically portrayed, Emilio Fernández’s directing is on point as usual, and the two music sequences, “Ave María” and “Malagueña Salerosa,” are perfection.

Los olvidados (1950) – Luis Buñuel’s

By subject matter alone, Los olvidados is somewhat of an oddity amid Luis Buñuel’s long filmography ranging from the utterly absurd (Un chien andalou (1929)) to sexually sleek (Belle de jour (1967)). Focusing on the lives of poor children in the slums of Mexico City, the film is a rather unsubtle social commentary on the effect of poverty on young people. It’s brutal in its realism – the characters are not idealized or ennobled by their strife, yet their socioeconomic status is also never implied to be due to their own failings: they’re victims of a larger system, a social disease known as poverty.

The story follows young Pedro (Alfonso Mejía) as he gets caught up in a street gang led by the vicious, nigh sociopathic Jaibo, played with disturbing brilliance by Roberto Cobo. The boys of the gang steal, fight, and even beat up a blind man, with Jaibo destroying the man’s instruments (his livelihood) for an extra dose of malice.

The film asks, would these boys be so bad, so cruel, if they had been brought up in loving families, with access to education and opportunities? Los olvidados seems to say that no, they would not be. But in the film, poverty goes hand in hand with cruelty, working as a vortex and sucking people right back into it, no matter how hard they may try to “go straight.”

Plagued with controversy from the very beginning, the Mexican public was furious when Los olvidados was released in 1950, but it has since gone on to become a classic, recognized for the excellent piece of cinema that it is.

María Candelaria (1943) – Emilio Fernández

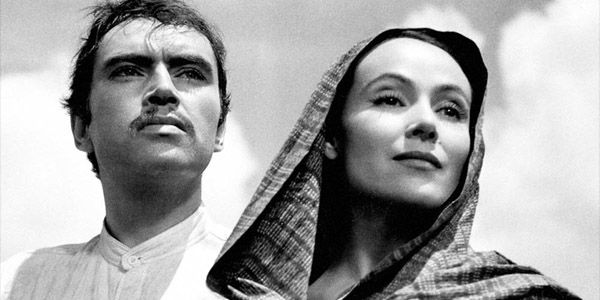

The first Latin American film to win the Grand Prix (now known as the Palme d’Or) at the Cannes Film Festival, María Candelaria is a precious film, a romantic tragedy from director Emilio Fernández. It stars Dolores del Río as María Candelaria and Pedro Armendáriz as Lorenzo Rafael, a poor indigenous couple ostracized by the rest of their community. Their only wish is to get married, but they don’t have enough money, so they plan on selling their piglet’s offspring once she is grown.

The film’s cinematography, done by the prolific Gabriel Figueroa, who frequently collaborated with Emilio Fernández, is breathtaking: wide-open skies scattered with thin clouds, sparkling waterways, mountains of flowers. In many ways, María Candelaria is a love letter to the natural beauty of Mexico.

It’s also interesting to see Pedro Armendáriz, a portrait of machismo, in the softer, sweeter role of Lorenzo Rafael. Armendáriz’s skill as an actor is what makes Lorenzo Rafael’s love for María Candelaria so palpable and endearing, the tragedy of their romance so heartbreaking. Naturally, Dolores del Río is lovely in this film as well, portraying María Candelaria with an earnest, almost naïve, sweetness that might well feel prescribed with another actress.

One of Mexico’s most beloved films, María Candelaria is a beautiful, devastating movie, a work of art unto itself. If you only ever watch one Mexican film, I’d say it’s a toss-up between María Candelaria and Enamorada, though María Candelaria might win out, just a little.

Ahí está el detalle (1940) – Juan Bustillo Oro

Sometimes humor doesn’t stand the test of time, but in Ahí está el detalle, the beloved Mexican comedian Cantinflas (Mario Moreno) is as fresh and funny as ever in 2018. Moreno’s character of Cantinflas is more or less a bum, a street-wise tramp. He evades any and all culpability with his “gift of gab”: senseless, meandering monologues that go nowhere and mean nothing, frustrating the other characters to no end.

In Ahí está el detalle, Cantinflas finds himself having to pretend to be the missing brother of a wealthy woman, which leads to a lot of silly situations, such as Cantinflas having to parent the missing brother’s children. The film’s humor relies upon misunderstanding, confusion, and straight-up absurdities reminiscent of the novel Catch-22. Cantinflas is a joy to watch, and his weird, unique brand of humor is so good that it’s easy to see why he’s been called “The Mexican Charlie Chaplin.”

Aventurera (1950) – Alberto Gout

Aventurera (“Adventuress”) has been called the best cabaretera film, a commendation that is quite well-deserved. The film is an absolute spectacle, a delight to watch, having a little bit of everything: film noir, Mexican melodrama, extravagant music and dance sequences, dazzling outfits, and a fierce performance by Cuban actress Ninón Sevilla, who sings the marchinha de carnaval song “Chiquita Bacana” while wearing a dress made out of bananas.

The film tells the story of a young woman named Elena, whose life falls apart after her mother abandons the family for her lover, leading Elena’s father to commit suicide. Elena leaves her hometown for Ciudad Juárez, where she is ends up working at a night club. Throughout the movie, we see Elena’s long descent into a sordid world of crime, sexuality, and revenge, becoming a heartless person by the end of it.

Dubbed the queen of the cabaretera genre, Ninón Sevilla is beyond phenomenal in this role, bringing the utmost of her vivaciousness to the dance scenes and a really chilling cruelty to the scenes with her mother-in-law (Andrea Palma), who’s also the madam of the first cabaret Elena worked at. And no Golden Age Mexican film isn’t complete without Miguel Inclán in a villain role, but this time with a twist.

Are there any other films you might suggest to viewers new to the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema? Let us know in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Madeline Hrabik is a writer, film buff, and amateur historian from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She is particularly interested in silent film, historical films, and the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema.