Experimental or avant-garde cinema is a style of filmmaking that utilises unorthodox methods of non-traditional narratives to create work that can only be described as unique. Initial examples of this mode of filmmaking include Lars Von Trier’s hybridisation of film and theatre in his 2004 exploit Dogville, or anything written and directed by David Lynch.

Von Trier and Lynch may push the boat out and disrupt cinematic conventions through their chalk drawn or surrealist narratives, however there is a whole other kettle of fish/filmmakers that reside within the experimental genre, who make the eccentric Von Trier and Lynch look sane in comparison.

Video artists Pipilotti Rist and Bill Viola not only rigorously reshape narrative structure, but they also consciously remould the laws of filmmaking to create visceral and holistic environments. Audiences sink into their worlds, and are submerged into unconventional cinema, which in turn creates an unforgettable and exceptional filmic experience.

Immersion

Before one can understand how it is possible for avant-garde filmmakers to heighten the audience’s experience and consume a spectator within their work, one must understand the meaning of immersion. Immersion is a process of disembodiment, with the audience projecting themselves into an alternative world.

The two main types of immersion are cognitive and sensory, and the best example of cognitive immersion falls within standard cinema; as audiences are plunged into an alternative space, they absorb their surroundings through cerebral understanding. It is sensory immersion, however, that video artists like Pipilotti Rist and Bill Viola manage to encompass, which allows their work to transcend dimensions.

Cognitive immersion, although immersive, disturbs the illusion of an autonomous fictional world. Simply, when one goes to the cinema to watch a film, the spectator is fully aware of their disconnection to the narrative. They are sat in a red velvet seat, staring at a screen in a room full of people sneezing and chewing on popcorn. They are consciously aware of the distance between themselves and the screen, thus providing weaker immersion.

Sensory immersion reaches outside of the screen, creating a corporeal moment. The goal is to blur the edges, and as performance art pioneer Allan Kaprow puts it: make “the line between art and life as fluid and indistinct as possible”. The material and virtual world morph together to become one, subsequently creating an embodied experience within real space.

Hybridising Film and Theatre

Rist and Viola have created a formula to heighten their work through combining the medium of film within an unconventional space, i.e. a studio that’s tailored to their work. As mentioned previously, Lars Von Trier brought theatre into the world of film, however Rist and Viola do the opposite.

A hybridisation between the two enable sensory immersion to take place because theatre is a hypermedium that has the possibility to manipulate and synthesise sensory perceptions. This means the immediacy (the direct connection between art and spectator) is transparent, and a perfect hypermedia system utilises all 5 senses which enables the possibility for deeper immersion.

Bill Viola

In relation to Viola’s work, he often uses multiple screens and surround sound audio within the space to engulf the spectator into his art. Interestingly, Viola uses “immersion” in more ways than one: water is a reoccurring component within his films, and he literally submerges his subjects in water to bring all definitions of immersion into play.

Viola’s 2001 film 5 Angels for The Millennium shows 5 individual sequences of figures ascending and descending through water. One of the locations he chose to display this video was at the Gasometer in Oberhausen, Germany. Previously used as a gas holder, the large container has a religious, sacred quality to it with its strong and sometimes harrowing acoustics.

As Viola also manipulates the passage of time through extreme slow motion, he creates his own realm with unconventional rules: the video revokes the progression of time, gravity and a linear narrative. Sound washes over the spectator like the water within the video, and the all-encompassing work permits the audience to feel the push and pull of the water themselves.

One critic notes that within this piece, “sensory immersion is intensified by the viewer’s lack of agency. The work requires the audience’s complete submission to the aura of the imagery”. Viola’s world becomes universal; no dialogue means his work communicates to all audiences through the senses. As the subject sinks, the spectator sinks, hypnotized by Viola’s transcending atmosphere.

Pipilotti Rist

Similarly to Viola, Pipilotti Rist is a visual artist and filmmaker who creates worlds for immersion to take place, however she also redefines the act of gazing (haptically and voyeuristically) which in turn sets up an exceptional experience through up-close tactile viewing. As the female body is a reoccurring theme within her oeuvre, she shatters then redefines its vocabulary to expose alternative representations, which provides a unique exploration of the female form – and she does this through the power of immersion.

Sensuality resides deep within the work of Rist, and in her 2008 video Pour Your Body Out, she uses it in a hyper-feminine manner, harnessing intense pink, peach and yellow colours, almost making them glow under her microscopic camera lens. She heavily colours, edits, merges shots together and zooms in, so the audience can see every minute detail of the body as it is projected onto the gallery walls, moving around in a lava lamp motion. The audience are provided with soft seating which they can lay upon to soak up the images swirling above them. She sets up a relaxing, corporeal experience with the soft surface of the seating matching the comforting imagery, thus drawing the spectator in through the senses.

Punctum

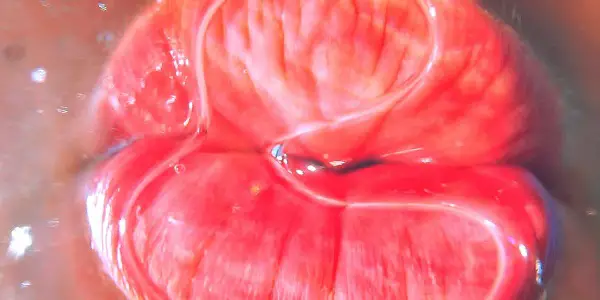

A prime example of how far Rist takes immersion can be seen in her 1996 film Mutaflor: Rist herself is the subject in this piece, and she is naked on the floor looking up to the camera from a worms-eye view. Once again in slow motion, the video begins, and the camera swoops into Rist’s mouth. The screen turns black and then a pull-shot is used, where the camera comes out of her anus, which then returns to her mouth and is looped over ten minutes. Mutaflor has been compared to a needle; by which Rist pokes at the spectators, asking for attentions from their obtuse perceptions.

This “needle” is known theoretically by Roland Barthes as punctum: ‘for punctum is also: sting, peck, cut, little hole-and also a cast of the dice. Punctum is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me.)’ The feeling of punctum “stings” the audience, and the volatile energy speaks to the spectator on a deeper level, for punctum is a holistic, individual experience that causes the spectator to be touched or pierced by the work.

Surrealism’s Influence

Mutaflor has been compared to the Spanish short film Un Chien Andalou (1928) by experimental filmmakers/surrealists Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel, who also disrupt normative narratives of cinema and the way in which the sexual body is perceived through editing and juxtaposition.

Similarly, they also display the disruption through unusual and taboo images of the body (the film depicts a razor being dragged across a woman’s iris and a hand with a hole in it secreting ants). Just like the surrealists, Rist sets up a dream-like state that speaks to the audience on a subconscious level. The outlandish isn’t questioned, for it is paradoxically understood by that part of the mind one will never truly understand themselves.

Viola also uses the dream state within his work, consider his exhibition aptly named The Dreamers (2013), where footage of people submerged in water surround the gallery. The tranquillity of the subject becomes contagious, and the implausible circumstances of people sleeping underwater draws spectators in, and Viola’s hypnotic abilities begin to take over.

The entire mise-en-scene of these works by Rist and Viola enable the audience to lose themselves in an intensified relation with another. The viewer becomes immersed, sometimes to the point where they begin to see themselves as the subject, for Rist is a metaphorical mirror and literal window into the body and Viola’s “Dreamers” have an attractive, timeless ambiguity present in oneself. Over time, the initial shock of the imagery disappears, and the eyes slowly adjust to these underwater beings and Rist’s orifices. The spectator begins to sink deeper and deeper into the artist’s work, as if enchanted by a loss of self, and through this the spectator ironically finds themselves in the presence of another.

Avant-Garde Video Art: Conclusion

It is undoubtedly obvious that film is immersive, why else would someone go to the cinema? They want to lose themselves in the story. It is also true however, that experimental avant-garde filmmakers have recognised the central reason for viewing and aim to synthesise it to create the ultimate immersive experience. Why do most filmmakers only utilise hearing and sight when they have all 5 senses at their disposal? The cinema can only take the audience so far, and it is that combination of film and theatre which exceeds boundaries.

Sensory immersion grabs the spectator and pulls them into the narrative, they themselves become just as important as the work, as they coexist in a temporary autonomous zone where they can share in the experience of what is being presented. Avant-garde films like those made by Rist and Viola only go so far. Yes, they reel the audience in, but immersion requires a collaboration: it needs the audience to hand themselves over to the art to let themselves be affected.

Vulnerability is essential if one wants to fall victim to immersion. The artist bares all so the spectator must do too. Perhaps that’s why experimental film is so niche or misunderstood; the strength it takes for a participant to be vulnerable is too arduous. The heart must be worn on the sleeve to achieve transcendence.

Who are your favourite experimental avant-garde filmmakers? Share your thoughts and comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.