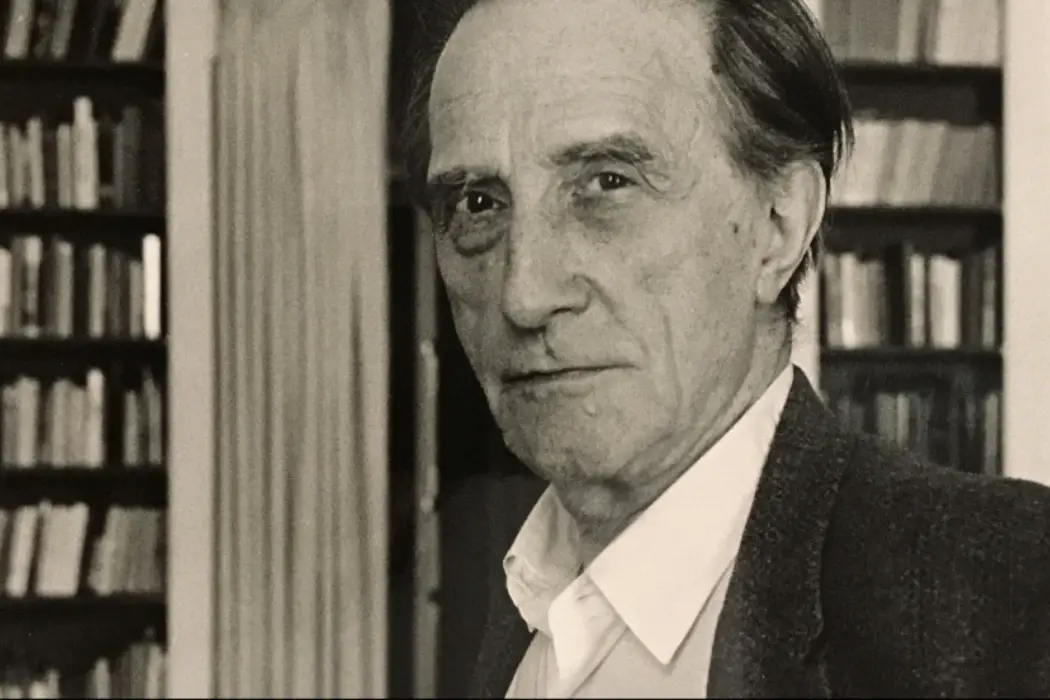

MARCEL DUCHAMP: ART OF THE POSSIBLE: How One Man Redefined Art

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster,…

It’s hard to think of 20th-century art without Marcel Duchamp. From his early experiments in Cubist painting to his revolutionary “readymades,” Duchamp’s work was consistently at odds with whatever was popular and accepted in the art world at the time. His influence can be seen on an entire generation of artists and art collectors who were forced to reevaluate their definitions of what makes a work of art, from Andy Warhol to Peggy Guggenheim and beyond.

Yet Duchamp’s legacy of breaking the rules is at odds with a new documentary about his life that bears more of a resemblance to a paint-by-numbers project than any of his groundbreaking pieces. Written, directed, edited and shot by artist Matthew Taylor, Marcel Duchamp: Art of the Possible is an unabashed love letter to Duchamp, chronicling his life from his childhood in Normandy through various highs and lows until his death in 1968 at the age of 81. The lasting impact of Duchamp is undeniable; the film, however, is not likely to linger long in your memory.

Rebel Rebel

Duchamp was one of three brothers who set out to become successful artists at the turn of the twentieth century, part of a new generation of artists whose work strove to connect the burgeoning avant-garde with the respected French tradition. Yet Duchamp almost immediately showed himself to be at odds with his peers with one of his most famous early works, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912).

By taking the long-established tradition of the nude in art and showing it in hyperkinetic movement instead of reclining on a sofa, Duchamp tipped the French art world on its head and shook it to the point of discombobulation. With elements of both Cubism and Futurism, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 was impossible to categorize, so the French preferred to ignore it. But, in the United States, the painting’s appearance at the 1913 Armory Show resulted in an explosion of attention and paved the way for Duchamp’s move across the Atlantic.

Changes

Duchamp wanted to introduce new, alien elements to his work and challenge the notion of what constituted a work “of art.” His piece 3 Standard Stoppages (1914) is a prime example of this idea at its best; Duchamp dropped strings from above onto pieces of canvas and affixed them where they fell at random, allowing chance to determine the outcome of the piece instead of any concrete artistic intention. But Duchamp is perhaps best known among more casual museumgoers for his readymades, which were found objects chosen by Duchamp and presented as works of art. (The “tampon in a teacup” that elicits so much disdain from Enid in the film Ghost World is another delightful example of this concept.)

Fountain (1917) – a urinal signed by Duchamp with the pseudonym R. Mutt — is perhaps the most famous and influential of the readymades, but it was by no means the only one; bottle racks, bicycle wheels and even an old comb were all presented as art objects in this way. Duchamp openly encouraged the replication of the readymades, allowing art curators to create their own versions for shows around the world. Whether or not you agree with Duchamp’s perspective, you cannot question that his work redefined what “art” was in the 20th century.

Marcel Duchamp: Art of the Possible employs a lengthy parade of talking heads, including many famous artists, critics, and collectors, to comment on Duchamp’s legacy, as well as archival recordings of the man himself and, of course, a great deal of footage of the works being described. It’s all neatly assembled and backed by a largely anonymous piano-based score, a perfectly acceptable primer to Duchamp that may appeal to those who have seen his work in museums but know little about the philosophies that led to its creation.

But Duchamp, an artist who never stopped challenging himself and his public and who spent the last two decades of his life creating one of his most thought-provoking pieces, Étant donnés (1946-1966), deserves more than a perfectly acceptable portrait; he deserves one that at least attempts to rival him in artistic exploration. In that regard, Marcel Duchamp: Art of the Possible is largely disappointing.

Marcel Duchamp: Art of the Possible: Conclusion

Duchamp rejected the idea of “retinal art,” art designed to merely please the eyes without presenting any real challenge to the brain. The irony is that Marcel Duchamp: Art of the Possible is essentially retinal art in documentary form; it provides a pleasant and appealing overview of Duchamp’s life and career without truly challenging the viewer.

What do you think? Are you familiar with the work of Marcel Duchamp? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

Marcel Duchamp: Art of the Possible is available on streaming services beginning March 10, 2020.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster, a killer Christmas tree, and a not-killer leopard. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Film School Rejects, Bitch: A Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Bitch Flicks, TV Fanatic, and Just Press Play. When not watching, making, or writing about films, she can usually be found on Twitter obsessing over soccer, BTS, and her cat.