Anime’s Mainstream Moment: Past, Present & Speculation

Christina Tucker is a NY-based production assistant and wannabe screenwriter.

A quick primer for the uninitiated: anime is a Japanese term, and refers to animation released by or in association with Japan. It is a medium, not a genre, and can be released in the form of television shows, original video animations, and films, sometimes adapted from manga (in general, a reference to comics) or novels. There are hundreds of anime production companies in Japan, with anime making up a large portion of Japanese DVD sales.

In the past decade we have seen the impacts of anime on Western animation in terms of both animation and/or narrative approaches, in particular in children’s programming; She-ra and the Princesses of Power, Voltron: Legendary Defender, Steven Universe, The Amazing World of Gumball, Avatar: The Last Airbender and Legend of Korra are recent examples. Those who were childhood fans of anime in the 80s and 90s are adults now, and as artists have incorporated early artistic influences into their work in Western animation.

A related phenomenon is anime’s rise in popularity, both in its original form and as source material for big budget live action film and television. 2018 in particular, has been a pivotal year for anime’s increased presence in in American entertainment and popular culture. Netflix has begun distribution of eight new exclusively licensed anime series, as well as securing streaming rights to Neon Genesis Evangelion, Goku from Dragonball Z appeared as a float in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade, Mamoru Hosoda’s 2018 film Mirai is nominated for a Golden Globe, Sora yori mo Tooi Basho (A Place Further Than The Universe) was listed as one of the best shows of the year by the New York Times, and Funimation, an American company focused on anime dubbing and distribution, is partnering with Hulu, among other anime-related stories.

Cowboy Bebop, Death Note, and Ghost in the Shell have recently been or are soon to be adapted as live action adaptations produced and/or distributed by major Western studios. Of particular note is Alita: Battle Angel. Quality of the finished project notwithstanding, Alita: Battle Angel will be a large-scale film produced by James Cameron, with a budget in the hundreds of millions and a cast with Academy-award winning actors. that is, at the end of the day, based on a 1990s manga franchise with an OVA released in 1993. It is not an obvious choice for adaptation, but will be pushed into American pop cultural landscape nonetheless.

Anime’s presence in the United States is not a phenomenon new to the 2010s, but the cultural opinions surrounding anime and “nerd culture” in its many manifestations have changed just in the past several years, and anime’s place in the American entertainment industry and its presence in the larger popular culture landscape seems to be on the verge of a big change. Anime, in America, looks to be on a similar path as superhero comics; initially somewhat niche, then popular in its own right, later adapted in other mediums, then, finally, pushed into a position of being both culturally unavoidable and financially successful.

American Distribution: A Brief History

Distribution of anime in America began in earnest in the 1980s, with a number of children’s anime and films, such as Adventures of the Little Koala, Maya the Honey Bee and The Littl’ Bits airing on channels such as Nick Jr. and The Family Channel. Cartoon Network and The Sci-Fi Channel (which had a dedicated anime block through the 90s and 2000s) also aired programs for older audiences. In 1988, Streamline Pictures was founded, one of the first companies solely devoted to English dubbing of Japanese anime, and although the quality of their output varies, their dubs of Akira and several films from Studio Ghibli (the production company founded by renowned animator Hayao Miyazaki) are admirable attempts at bringing anime to an audience that would otherwise not find the medium accessible.

VHS had vanquished Betamax as the king of the so-called “videotape format war,” and the market for anime (known as “Japanimation” until the mid-80s) in America grew quickly with the increased accessibility of home video. Bootleg VHS tapes, manually subtitled by dedicated fans (“fansubbed”) and traded like black market commodities would soon be replaced by official subtitles and dubbing. A number of companies, including Bandai, Funimation, 4Kids, and Viz Media, among others, began licensing anime in the United States.

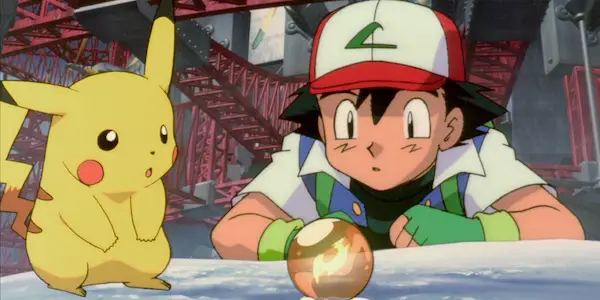

These years also mark the beginning of several long-running and well-known anime franchises such as Sailor Moon, Pokemon and Dragonball Z, which came to America during this period and remain recognizable to many non-anime fans. 1998 also marks an important moment in terms of American acknowledgment of the legitimacy of anime; Disney’s partnership with Studio Ghibli began, a partnership that still exists to this day which allows for wide releases of Studio Ghibli films in the US, as well as high quality English dubs with star-studded casts.

Anime and the Internet

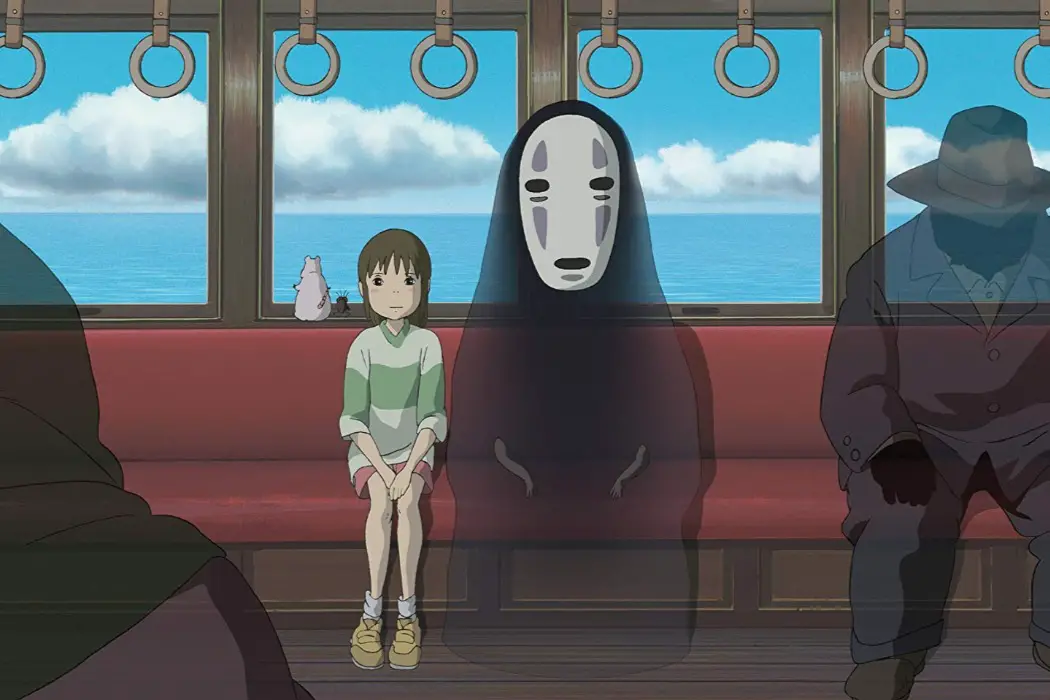

By the early 2000s, anime had further expanded into the American entertainment industry. Spirited Away was released through Disney and nominated for an Academy Award in 2002, and channels such as Jetix (now Disney XD), Cartoon Network, Syfy, and WB were airing anime in their programming. The prevalence of anime, with animation still largely considered a medium tailored exclusively toward young children, was cause for distress for many parents, particularly when accompanied by the rise of Internet use among young people.

There were memorable arguments in the early 2000s about the effects of the objectionable or simply mature content in media of many kinds, including violent and sexual content in video games and the increased prevalence of online pornography. Conversations about censorship, parental guidelines, and cultural norms sprang from a moment of rapidly developing technology and children whose entertainment was becoming increasingly difficult to control, and anime did not escape scrutiny.

Many articles from that period of time that seem, today, impossibly dramatic and often naïve, particularly with today’s standards for entertainment, but the period was, to those who remember it, one of genuine concern for parents unused to the unfettered access television and later the Internet provided to their children. This was a period of time that brought technological responses to parental concerns such as Net Nanny, released in 1995, used to monitor and restrict Internet access, and the FCC’s “V-Chip,” used to block inappropriate television programming.

Jim Rutenberg, for the New York Times, in 2001, warns parents of these newly imported and supposedly hyper-violent cartoons: “The success of the ”Pokémon” cartoon show jumpstarted the genre two years ago and then others upped the ante in violence….” and, referring to shows airing on children’s television networks, “Many of the shows are imported directly from Japan, where the public’s tolerance for blood and guts on TV has traditionally been much higher than it is in the United States.” Another article published in the Chicago Tribune in 2002 describes anime as ”a style of cartoon animation that began in Japan in the 1960s; it often depicts futuristic scenarios starring characters who are both wide-eyed innocents and violent, sexualized beings.” These generalizations about anime are held as truth by many, particularly older audiences, and are only recently starting to fade.

Despite complaints, as it stands, almost every form of entertainment is easily accessible to any American with an Internet connection. One impact of the nearly instantaneous access provided by the Internet is the unstoppable development of a popular culture vernacular, one that incorporates a base knowledge of seemingly disparate mediums; knowledge of film, television, memes, video games, comic books, anime, and the major players on various social media platforms are all involved in understanding much of the language of young people the Internet. This development and the heightened bar for pop culture literacy is only possible due to the accessibility the Internet allows.

As a result, nearly every once-niche form of media seen as a part of so-called “nerd culture” is easier to come by, and barriers for entry to the world of anime are lower than ever. A plethora of anime can be purchased in hard copy easily online, rather than having to be painstakingly sought in niche video stores. Anime can also be viewed online on a variety of platforms such as Crunchyroll, Netflix, YouTube, and Hulu, not to mention dozens of illegal streaming websites. Research on anime can be done about animators and directors with ease, and discovering new titles and artists and discussing with other fans is all easier than ever. Anime, particularly for young adults, is not only becoming well-known, but acceptable, accessible, and expected to be at least vaguely understood by the general public.

The Future

The aforementioned history of anime distribution and popularity in America tracks, in general, with the explosion of superhero comic adaptations, likely, as with anime, due to the Internet and the democratizing nature of Internet culture. Superhero films went through a similar renewed interest in the 1980s, explosion in the 1990s and 2000s, and continued expansion through the 2010s to the colossal Marvel and DC cinematic universes that exist today.

The 2010s are a pivotal moment for this continuation of nerd culture’s legitimization through big budget, mainstream media. Comic book movies, for example, are for everyone, not just die hard fans, and despite attempts at gatekeeping to maintain exclusivity around the art form and its fandom, comics are thus a hobby more accepted socially and more easily accessible by the general public than in previous decades. Anime seems to be reaching this cultural point at only a slightly slower pace.

One question is Why? I ask this question not only in terms of technological advancements, in which case the question leads to simpler answers involving as ease of access due to the Internet and development of home video technology, but in terms of artistic taste. One can only speculate. Perhaps people tire of the big budget entertainment system, in all its forms, and the exploitative, morally ambiguous stench that has recently become impossible to separate from it, and people seek media that feels more independent. We can see this in film, with the meteoric rise of production companies like A24 and Annapurna. Similarly, it is likely that the Western animation styles of powerhouse animation studios like Disney and Dreamworks have come to represent something negative for American viewers of animation, whether it be media conglomerates and their monopoly over a medium or the lazy exploitation of a fanbase’s nostalgia.

Indie or niche status is hard to maintain after a culture or art form is shown to be popular enough to exploit. Much like video games and comic books, as soon as a nerdy niche becomes popular enough, its mainstream appeal begets brand recognition, and soon enough everyone from advertisers to production companies to celebrities and their management teams are scrambling to capitalize on a cultural obsession. Popularity is a difficult line to walk; overexposure and boredom can happen quickly, and many socially conscious young people will feel compelled to abandon something (an artist, a franchise, an app, a political movement) as soon as an out-of-touch corporate presence is made too obvious, or underlying capitalistic goals are made too apparent.

There is nothing to do but speculate on the effect increased interest in anime could have not only on the medium but entertainment in general. Already mentioned is the increased use of anime and manga titles as source material for big-budget live-action adaptations, for which I want to maintain hope. Another is the increase in original anime series distributed by streaming services as seen with Netflix with titles such as Aggretsuko and Devilman Crybaby, and Hulu’s partnership with Crunchyroll.

Major streaming and production companies are more willing to partner with anime producers to distribute, whether exclusively or not, quality animation, bringing these series worldwide on an accessible, mainstream, and widely popular platform. Another result of anime’s current moment in America, one that I have already seen on social media, is that more people of all ages are willing to seek out anime and gain a new perspective on the possibilities of animation.

Can a medium or artistic approach maintain its unique qualities and artistic integrity while becoming well-known and well-funded? Can we can reach a stage of quality output, access to source material, and genuine creative expression in and around anime distribution and adaptation without reaching the current level of exhaustion that threatens the longevity of superhero franchises, or is this a demand to have our cake and eat it too? It’s easy to feel resentment for new fans of anime who seem to be cashing in on a cultural fascination, but the future could be bright for old and new fans alike.

Anime is a medium that offers a wide range of source materials, in a variety of genres and appealing to different age groups, that if well-adapted, more widely distributed in the United States, or referenced indirectly through visual or narrative inspiration, could both maintain the best that anime has to offer and allow the medium to find its place in American culture.

Have you perceived a change in prevailing cultural opinions regarding anime? How do you feel about these changes, particularly if you were a fan of anime in your childhood?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.