Animation Sensation: THE PRINCE OF EGYPT: Or, How To Make A Religious Movie The Right Way

If there is one word that can sum up Dallas…

As someone who has seen a lot of films, I can say that there are two genres of films that do not strike my fancy as a whole: romantic comedies and religious movies. I find both genres smarmy and filled with cliches and predictability that lead to eye-rolling so egregious that, sooner or later, an optometrist will be required. I love cinema, so I prefer to keep my eyes as healthy as possible to continue doing what I love. My ire is primarily placed on the latter of the two. Most religious films I have come across features lazy writing, trite characters, and a sense of holier-than-thou anti-aphorisms that come off as more arrogant and less moral.

But with every rule, there is an exception, and my lack of taste for most religious films is no exception. Two films come to mind when I think of religious movies that I enjoy: the 1993 Bernardo Bertolucci family drama of Little Buddha and 1998’s animated musical The Prince of Egypt. Both films are sumptuous visually in their way, tell the story of a prominent religious figure, are written with family viewing in mind, and hit me right in the gut every time I watch them. However, as much as I enjoyed Little Buddha, this is Animation Sensation, so the focal point will be on the animated film of the two. Here is why The Prince of Egypt is the right way to make a religious movie.

It Ain’t Easy Being an Israelite!

The Prince of Egypt is set in Egypt during the time of the Pharaohs, and the movie starts with a bang. As is required of all great musicals, the opening song, “Deliver Us,” gives the viewer a glorious and grotesque view of the life of a Hebrew slave. Egyptian drivers push their slaves to the limit as dust, grime, and sweat cakes the skin of the Hebrews with only the phrase “faster!” accompanied by a whip careening against sun-exposed skin for those who did not comply with the outrageous quota of work for the Egyptian empire.

This story is told in greater detail in the second book of the bible of Exodus. But The Prince of Egypt takes a few liberties with the original biblical tale and makes the Exodus story tighter paced and emotionally resonant. As the song continues, the viewer is introduced to the classic tale of how baby Moses, escaping the subsequent Hebrew infanticide campaign, was placed into a small arc and put into the Nile River only to be discovered by the Pharaoh’s daughter, who raises baby Moses as her own. For his entire life, Moses was raised as an Egyptian prince and thought nothing of the suffering of his fellow Hebrews as he grew into a headstrong and pampered young man.

What makes The Prince of Egypt work so well from a thematic point is that, although this is considered a “family film,” the movie does not belittle the intelligence of its younger viewers. The stakes, at times, can be dire. Characters get hurt, scenes of workers being whipped and tortured are all shown with a sense of realism that evokes a sense of pathos in younger viewers.

Sickness and pain abound, characters die, and when something is demonstrated that exemplifies the more tragic aspects of the human condition, The Prince of Egypt does not shy away from showing it. And it does all of this by being non-exploitative and with tastefulness, which ensures that, although this is a film meant for children, the creative team behind this gem did not want to lie to them.

Shades of Grey

A prominent trait in many films geared towards a younger audience is the black-and-white villain. For the sake of candor, it is worth noting that family entertainment is becoming less heavy-handed with how villainy is portrayed. There are several antagonists in such media that are sympathetic where younger viewers can, to a certain degree, understand the motivations behind why an antagonist acts in the way they do. The Prince of Egypt does this well, and in regards to its old-testament source material, if the bible is the older, black-and-white way of writing an antagonist, The Prince of Egypt is the modern version.

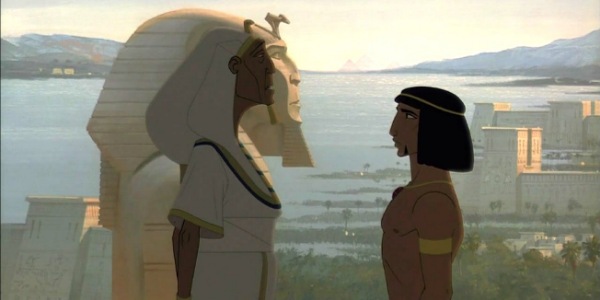

In the bible, Ramses, the great Pharaoh of Egypt, is mentioned as someone of pure evil, a man to be hated and feared for his slavery and oppression. But in The Prince of Egypt, a different story is told. Ramses is portrayed as a conflicted man, a leader with a vast superiority complex, plagued by the anxiety and obsession with proving that he was a better leader than his father. Going back to the biblical source, the story of Exodus, while stating that Moses and Ramsees were adoptive brothers, no further exploration into the nature of their relationship is given. On the other hand, the Prince of Egypt exhibits just how close the two brothers were. In the film, they are best friends and engage in all kinds of hijinks and tomfoolery together.

Everything in life is going well for Moses and Ramses. They lead cushy lives, have all of the fun they want, and enslaved people do all of the work. Things take a turn for the tragic, for when Moses discovers his heritage as a Hebrew, he leaves his upper-class life behind, and Ramsees is distraught by losing his brother. This is another plot point that, while not explored in the bible, makes The Prince of Egypt a champion in character development. Rameses is not portrayed as a bloodthirsty villain, as shown in the biblical account or other Exodus tale adaptations like The Ten Commandments, but as a heartbroken man who wants nothing more than to have his brother join the family again. Even during scenes where Ramsees is angered by the plagues Moses’ God has cast upon Egypt, Rameses still asks Moses the heartbreaking question of “why can’t things be the way they were before?”

His character is brought to life due to the fantastic voice acting of Ralph Fiennes, mixing a regal charm laced with a snake-like venom of arrogance. He can be warm and loving in one scene, followed by smug hubris as he regales himself with the title of “the morning and the evening star.” He is a delusional despot, but the way he is written and the voice acting of Fiennes never take it to a degree of hate-worthy for the viewers. It would have been easier, considering the target demographic, to make Rameses into a superficial “mustache-twirling” villain, but The Prince of Egypt sidesteps such a plot pitfall.

My God is stronger than your God!

As I have mentioned earlier, religious movies (especially those of the Christian persuasion) are not my cup of tea. One of the most significant defects of films about faith is the snide way most religious movies depict non-believers of said faith. As a means of proof, pop in any DVD or go to the Christian streaming service PureFlix to understand the topic at hand. An egregious example is any faith-based movies of actor-turned-religious-activist Kevin Sorbo.

His biggest “hit” in the lexicon of Christian films is the laughably out-of-touch God’s Not Dead film series, and all of the tropes and formulas of a lot of Christian movies are on weak display. Many religious-themed films are one-dimensional Hallmark Channel styled fare with a dash of persecution complexes, the othering of non-Christians, and paper-thin plots. For the record, I am not doing this to attack Christians, and several Christians I know have made the same complaints about religious media.

The Prince of Egypt is Judeo-Christian and espouses the values of faith, and even for a non-believer such as myself, I was drawn into its world, and one of the biggest reasons for this is a simple factor: It does not shame those who are non-believers. Rameses and the Egyptians are not punished for being pagans; Moses did not come back to Egypt, saying, “convert or face the consequences!” No, his admonition was, “Let my people go!” The battle between Moses and Rameses is not one of who has the true religion. It is one of morality and the fight against slavery. Rameses is not being punished because he prays to Rah or gives offerings to Bast, but because he is a slave driver and lacks humility.

The Prince of Egypt also does commentary about how organized religion can lie to people and is used as justification for the mistreatment of others. A hallmark scene is when Moses finally returns to Egypt after receiving God’s message from the burning bush in the desert. After being reunited with Ramses in his royal court, proclaiming for the emancipation of the Hebrews, Moses sets down his staff and, in a low tone, says, “Behold, the power of God.” The staff turns into a king cobra, and an undeterred Rameses enlists his high priests Hotep and Huy to show the powers of the Egyptian pantheon.

As shown throughout most of the film, Hotep and Huy are bumbling fools, and why anyone would follow their spiritual advice is beyond the viewers’ comprehension. An infectious musical number called “Playing with the big boys” blares, upon which the two priests engage in a series of smoke and mirrors to befuddle and belittle Moses. In every sense of the phrase, they are snake-oil salesmen, even talking under their breath about how much the crowd “loves” their performances. They spout ideals of piety to their gods. Still, in several parts of the film, they act as though their beliefs are shaky at best, utilizing religion to maintain power over their parishioners. The Prince of Egypt shows them for their frauds, an example of the faithless leading the faithful, and their false faith is the problem, not necessarily because they are pagan.

Juxtapose this moral with that of the “morality” of many modern-day religious films. Anyone who is not a Christian in faith-based cinema is presented as caricatures, such as the grumpy-atheist who did not come to their conclusion of disbelief due to rational thought but based off of past tragedy or, more dubiously, because they “want to sin.” Other religious groups do not fare better. Movies like God is Not Dead showcase Muslims as walking stereotypes, complete with overbearing fathers and docile women. Such cinematic grandstanding is not the correct way to show your religion to non-believers, most will resent such representation, and a change of heart is the farthest thing from a course of action they will take.

The power of animation

Animated features like The Prince of Egypt are why something like Animation Sensation exists. Animation is a powerful art form that tells stories and exhibits visual feats that live-action could only hope to achieve. The animation in The Prince of Egypt is sumptuous and gives credence to the epic myth of the story of Exodus.

Every shot, from the towering pyramids to the gargantuan alabaster stones of Pharaoh’s palace, have a breathtaking scope making the viewer feel small in comparison. An ancient empire like Egypt spanned a lot of lands, and this film shows just how mighty the kingdom was. The natural background of the Egyptian desert, particularly the scene where Moses leaves Egypt and traverses the dunes alone, makes the viewer feel parched and desolated and leaves me feeling like the relentless heat of the desert was beating upon me.

The character designs are noteworthy, with a hybrid of mythological and historical attention to detail. All Egyptian characters are true to ethnic form, avoiding a common complaint I have with other forms of media centered around Egyptian history/myth: whitewashed characters. But in The Prince of Egypt, the character designs look like the very hieroglyphics that line the walls of the palaces and pyramids of ancient Egypt. The people of this feature look, well, Egyptian and the various Afro-Arab peoples that assembled in such a society.

As for other aesthetic points of the film, aside from the visualization, the sounds of The Prince of Egypt are worth listening to on their own. The music of this feature is fantastic, whether it is the powerful ballad of “Deliver Us,” the delighted dance number of “Heavens Eyes,” or the hypnotic and seductive villain song number “Playing With The Big Boys,” The Prince of Egypt has several standout songs. And as for the score itself, composed by Hans Zimmer, listening to such pieces as “The Burning Bush” is always a shot through the heart. It’s a piece that starts as ethereal and calming, then bursts into an explosion of emotionalism. It has always perturbed me that the score for The Prince of Egypt did not win an Oscar.

Buried in the sand

Much like the sands of time, The Prince of Egypt has been somewhat forgotten. The film only came out in 1998, it was financially successful at the box office, and other critiques appraise it as highly as I have. Yet, it has been swept under the rug and relegated to the knowledge of only those who wear the badge of an animation buff. One would think that a Judeo-Christian society like America would show The Prince of Egypt more consideration.

To add insult to injury, several older animated films have been given the BluRay treatment, being re-released in special edition formats in some form or another. As for The Prince of Egypt, while it has a BluRay release, the design is laughably sophomoric and makes it look like a direct-to-video release. Maybe in time, fans of this film will be given a proper BluRay release that will be overflowing extra features and goodies that will make purchasing a special edition all worthwhile.

The Prince of Egypt has not convinced me to join any Abrahamic religion or has made me a believer in any way. But then again, I don’t think that is the film’s point. The Prince of Egypt is not a 95-minute conversion exercise but a beautiful representation of a cultural landmark, an animated taste of Jewish mythology that was 5000 years in the making. The themes of hope, escape from bondage, and finding your place in the world is universal and can be appreciated by anyone, pious or not. I may not be performing miracles by writing this since The Prince of Egypt will probably stay relegated to the dust bin of animated features. But even a non-believer such as myself can hope that more will be exposed to The Prince of Egypt due to my efforts.

Have you seen The Prince of Egypt? Is it just another animated film to you, or is it a powerful exploration of the human condition? How dares it fare when compared to similar films, or the Exodus story itself? Leave your comments below!

Release Date: December 18, 1998 United States

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

If there is one word that can sum up Dallas Marshall, it would be weird. He is a strange fellow who is also a writer, anime nerd, and film buff who can also talk for hours about mythology and out-there literature. He has been sighted at local used bookstores perusing for horror books and manga. He has also written a book about Japanese animation called Anime Adrenaline! Which can be found on Amazon. You can also catch him on his own website at www.Dallasthewriter.com