Anarchic Cinema: Jean Vigo’s ZERO FOR CONDUCT

Matthew Roe is a director, writer, producer, film critic, theorist…

So we’ve come to a turning point in our conversation. Up until now, we’ve discussed several incarnations of artistic anarchy in filmmaking, but primarily in the variant field of filmic nihilism. Though what has been discussed in previous installments is essential to understanding this cinematic theory, there is a glaring blind spot that has yet to be addressed: the sociopolitical. Of all movies that should be quoted in propelling the idea of anarchy in cinema, those films that literally lean on real-world political ideations and repercussions as the means in which they achieve dramatic and drastic change, are the best possible examples in those breaking the cinematic form.

That isn’t to say that all Anarchic Cinema aligns with the anarcho-political sphere, as you will find that to be a gross misinterpretation of my desired intent. Though it is true, I identified myself as an anarchist in my teenage years, I’m far less wide-eyed about their point of view than I once was, seeing (like most sociopolitical theories) pros and cons to adhering strictly to one general ideology.

The films I will be referencing for the next couple entries are not only politically-infused stories, ripe with counter-societal themes and characters, but also prime examples of those works uniquely breaking the conventions of filmic storytelling in order to equally explore the form as well as heavyweight themes. If you were laboring under the impression that the nihilistic subset of anarchic filmmakers were the only ones of note, we’ve hardly begun. Regardless on our own political alignments, there are few better movies to begin this particular conversation with, than possibly one of the most famous and highly controversial anarcho-centric films ever made: Jean Vigo’s Zero for Conduct (Original Title: Zéro de conduite).

Jean Vigo: A Bit of Background

Vigo spent most of his childhood in guarded anonymity due to his infamously militant anarchist father Eugène Vigo, who publicly wore the pseudonym Miguel Almereyda, an anagram for “this is shit”. As the co-founder and lead writer of Le Bonnet Rouge, a French satirical anarchist publication, Almereyda was constantly hounded for his hypercritical socio-political editorials and activism, often landing him in prison. He was found dead in his prison cell in 1917, strangled by his bootlaces. Though it was officially ruled a suicide by the courts, the autopsy proved exactly the opposite, which then amended the public notice that he had been killed by fellow anarchists as a means to shore up their cause. This position was later widely refuted; his son was only twelve-years-old at the time.

Jean Vigo was constantly in poor health throughout his childhood, exasperated by his mother Emily Clâro loading him off on relatives and boarding schools after Almereyda’s murder. As he became thoroughly estranged from his mother through discovering her indirect role in the misinformation surrounding his father’s death, the young Vigo became a rebel searching for his father’s innocence, all the while navigating the realities of then-contemporary France recovering from World War I.

During this time, Vigo would contract tuberculosis and be sent multiple times to sanitariums, where he would eventually met his future wife, Elisabeth Lozinska. The pair were quickly engaged upon their mutual release from the institution and settled in Paris. Though he secured a position on Abel Gance’s landmark film, Napoléon, Jean Vigo’s illness kept him from working, eventually finding a position as assistant cameraman on Louis Mercanton’s Vénus. Though this was a promising start to his career, no work came afterwards, with Vigo eventually resigning himself to ask his father-in-law for financial aid.

Vigo would use some of these funds to purchase his first (albeit second-hand) film camera, though his first attempts at camerawork ended in severe disappointment. He resolutely refused to work as a camera operator on any subsequent films, including his own. Though I am uncertain as to how, while the young couple battled their mounting medical issues and metropolitan poverty, and Jean Vigo struggled to get his first film project off the ground, he would meet his greatest collaborator and friend: Boris Kaufman. Kaufman was a Soviet cameraman would would go on to not only shoot all of Vigo’s films, but to be a pantheoned Academy Award-winning cinematographer, working for the likes of Elia Kazan, Sidney Lumet, and Jules Dassin.

Poetry and Boarding School

Jean Vigo and Kaufman would go on to be the most significant pair of pioneers directly responsible for the Poetic Realism movement of the 1930s and later the French New Wave of the 1950s (with many prominent filmmakers, such as Jean Cocteau, Luis Buñuel, and Pierre Chenal confirming direct inspiration). This small, highly influential cohort of films were rarely successful at the times of their original releases, and have often been overshadowed in the greater of film history by the impact of the French impressionists (who directly inspired filmmakers like Vigo) around the same period.

The cinematic landscape was flooded with Hollywood romanticism and commercialism, with the only homegrown films gaining acclaim and box office being those of the more popular impressionists like Gance. While also heavily influenced by the (less popular) surrealists and the hard life Europe was currently undergoing, the poetic realists made the lives of downtrodden and dejected their reality.

While Hollywood would usually throw their characters through the ringer only to emerge triumphant with a fairy tale ending, the impressionists introduced variant perspectives and mental states throughout more realistic journeys, with their conclusions often a toss up between good or bad, some being completely void of any catharsis. While this is a gross oversimplification of these two schools of filmmaking, these core differences, swirling with the sociopolitical climate, provided the backbone from which Jean Vigo and the poetic realists would find their stride.

Often these films would focus on loss, entropy, and death; all the while cloaked in brimming passions for life, love, art, and everything in between. These works and their creators were essential in introducing one monumental concept into film: recreated realism. In other words, storytelling geared toward an intrinsically accurate, yet aesthetically-charged representation of everyday life. Often protagonists of these films were the fringed elements; their dramatic arcs exploring poverty, the working class, and the sovereignty of individuals in modern society.

What’s the Skinny?

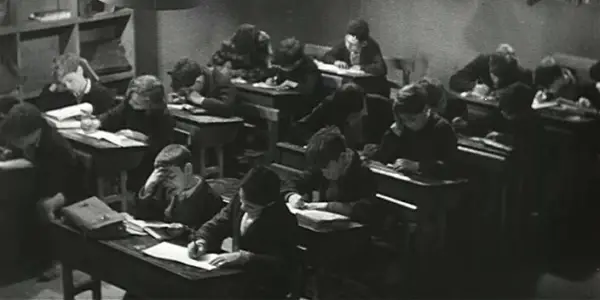

This brings us to the film at hand (“Finally!” I hear you yell). Drawing extensively on his own educational experiences, Vigo’s Zero for Conduct is a biting socio-critical satire, set in a repressive boarding school for boys, where the staff is overcome by an unruly student-led uprising. Shot from December 1932 to January 1933, Jean Vigo utilized a mostly non-professional cast, often picked right off on the street. The title is in reference to a common administrative punishment preventing a student from leaving school grounds with their peers on Sundays.

The four main characters are Tabard (Gérard de Bédarieux), Caussat (Louis Lefebvre), Colin (Gilbert Pruchon), and Bruel (Coco Golstein). They are not the smartest, nor the most popular students, nor are they the worst or best behaved. These students are just like any other, and they take any chance they get to assert any possible autonomy in their lives, much to each instructor’s chagrin. Though this does take the occasional shape of outward pranks and “attacks” on their least favorite adults, this gaggle of guys understand how much they can actually get away with while still superficially obeying the rules.

However, unlike many incarnations of such character dichotomies, we are never meant to feel any empathy for those authority figures curtailing the boys’ behaviors. While the kids just want to roughhouse and be boys their age, the headmaster spends an inordinate amount of time placing his hat in just the right position on his mantelpiece, the school monitors steal students possessions, and it is heavily inferred that Tabard may be the victim of molestation at the hands of an instructor. In actuality, with the exception of Huguet (Jean Dasté), a newly appointed supervisor with the proclivity for imitating Charlie Chaplin, all of the adults in this film are in some form despotic and corrupt. Caussat, Colin and Bruel become the masterminds plotting an actual physical takeover of the school’s Commemoration Day celebrations, where they assert their own control over their lives whilst thumbing their noses at the hapless grownups trying to control them.

Where’s the Anarchy in Zero for Conduct?

“Well that’s a silly question,” you may be asking, “Obviously the proof is in the pudding, and the central story is all about bucking against authority and embracing chaos!”. Well, as far as that goes, you’re marginally correct. In actuality, Zero for Conduct goes far beyond one core statement and manages a seriously impressive hat trick of feats. As we’ve said, Vigo appeared to be heavily inspired by the impressionists of his day, so what was initially paramount was not the plot, but the visual methodology by which we introspectively explore characters.

However, unlike the impressionists, using their evolving technique to better understand how we perceive and absorb the world around us, Jean Vigo took the journey to the realm of daydreams and idealism. It wasn’t just about how we physically and mentally react to the world, but how we mentally shape it for ourselves, and how we project those perspectives on those around us. Many scenes are filmed with an almost dreamlike quality, utilizing free association, variant speeds of film and dialogue, and manipulated sound design to produce an almost otherworldly effect. How we feel, in relation to what we see, is pedestaled higher than actually understanding what has transpired. In other words: style is equatable to substance, style is substance.

Bruce Hodsdon, writing for Senses of Cinema in 2013, is quoted saying, “Zéro de conduite does not comment on anything; rather it directly expresses a revolutionary sensibility…” He goes on to quote film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum by stating that school, “is simply no ordinary place where strange things occasionally happen but a poetic universe we all instinctively know.” That is where the majesty of Jean Vigo’s vision collides with the idea of anarchic cinema. It’s not for necessarily proving a point (though that indeed happens), but to visually manifest an experience that we all collectively share. To fully clarify however, we need to return again to the current definition of anarchy: “a state of disorder due to absence or non-recognition of authority.”

This determination is only made sound by its anchoring to the idea that adherence to authority is the natural way of life; that someone naturally is imbued with “the power or right to give orders, make decisions, and enforce obedience.” Also, that when we refuse to acknowledge this dominance, we are in a state of chaos, the natural way is disrupted.

Jean Vigo, simply by exploring the imaginations, dreams, and shenanigans of ordinary children, manages to make a profound statement that life (and likewise art) is intrinsically the opposite. He manages to poetically engage societal norms and mores, challenging their validity and import, while never denying the reality of contemporary society (as his criticisms and interpretations still hold significance in today’s world). Almost as if he is saying, “Society is the way it is, it’s not as natural as it ought to be, but here’s how we can join the two”.

The Legacy

Zero for Conduct was incredibly ahead of its time in the same instance being exactly emblematic of of its era. The film digs into conversations that weren’t happening in film: Sigmund Freud’s polymorphous theory of sexuality in children, the role children play in shaping modern society, and what actually is the natural state of the world. Though psychologists, sociologists and philosophers had been debating these concepts for years, in some cases centuries, rarely before or since had a work of art managed to capture these difficult conceptions into such a sublimely poetic form. Does it always make sense? No. But that’s just like life, not everything has a definite cause, nor does everything follow a logical through-line – sometimes shit just happens.

When it premiered in Paris on April 7, 1933, many members of the audience jeered and booed, some critics lambasting the film for its seeming ridiculousness and incredulity. However, the reactions were heavily polarized, with some championing Jean Vigo as one of the greatest filmmakers alive. Regardless of how an individual person perceived the film, Zero for Conduct was banned in France till after World War II, when it was rediscovered and screened in a revival of all Vigo’s films. It also went on to directly inspire François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (1959) and Lindsay Anderson’s if…. (1968), where numerous references can be easily spotted.

While a flurry of names and titles is all well and good, the true legacy can be summed up in another quote by Truffaut, saying that films of this kind “bring us back to our short pants, to school, to the blackboard, to vacations, to our beginnings in life.” ‘Our beginnings in life;’ in other words, these films help us to remember the innate state of humanity, before the pressures and impositions of adulthood force us down a different, more unnatural path.

Though we are all equitably the same at first, that is soon supplanted by perceptibly powerful minority classes foisting weaker majorities (usually monetarily and systemically) into accepting and following the smaller entity’s rationale. This is exactly what the film has in its cross-hairs, though whether these social constructs are effectively hit by the film is entirely up to you. For me, on numerous conscious and subconscious levels, Zero for Conduct is one of the most honest examinations of humanity and human society yet made in cinematic form. That is Anarchic Cinema.

What are your thoughts on Jean Vigo’s Zero for Conduct? Do you think it holds true to the idea of Anarchic Cinema? Tell us your thoughts in the comments below!

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Matthew Roe is a director, writer, producer, film critic, theorist and historian, with over 12 years experience producing film, video, television, and online content. He currently writes DVD/Blu-ray reviews for Under the Radar Magazine, movie reviews for Film Threat, and contributes features to the Anime News Network. He has won two Vollie Television Awards, an Honorable Mention at the LA Movie Awards, and is a Cult Critic Award Finalist. Matthew is a member of the Political Film Society and the Large Association of Movie Blogs.