Curb Your Adaptations: On Animation & Live-Action

Hazem Fahmy is a poet and critic from Cairo. He…

Like most people, my experience with animation started when I was a child watching kids’ cartoons. I worshiped Cartoon Network and tuned in religiously to their signature late 90s and early 2000s programming. Courage the Cowardly Dog, Dexter’s Laboratory, Ed, Edd n Eddy, and Samurai Jack, not to mention reruns of Hanna-Barbera classics like Scooby-Doo, Where Are You!, The Flintsones, The Jetsons, and Dastardly and Muttley in Their Flying Machines, were all instrumental to developing my love for cinema and television from an early age. I didn’t just love these shows for their brilliant humor and colorful characters, I loved them for the spectacular ways they used their form to bring to life said humor and characters.

The best works across all artistic mediums are ones that know how best to utilize the conventions and unique aesthetic opportunities of their mediums. A hallmark of great films is their inability to exist in any other form. In other words, their narrative and characters are so firmly rooted in the language of cinema that the story could not have possibly been told in any other medium.

Animation Excellence

This relationship between a work’s excellence and its medium is even more profound when it comes to animation. On a fundamental level, animation offers a unique level of freedom that live-action can barely compete with, even with the continuing growth of CGI. This is, of course, due in part to the fact that you can essentially draw or generate whatever the hell you please, but it is also due to animation’s heightened suspension of disbelief; it is simply much easier for us to accept a talking animal completely disregarding the laws of gravity when the image is so clearly fabricated. The finest animated shows and films understand this freedom, and they use the hell out of it.

This is why I hated the 2002 Scooby-Doo film. And I mean hated it. Even without having any of the language at the time, it just felt…wrong: an unholy thing that should never have been made. And it wasn’t because of the hokey script, the crappy CGI, or the forced performances (but, my God, they sure didn’t help), it just made no sense to me why a world like Scooby-Doo’s, that is so perfectly tailored for animation, would even attempt to exist in live-action.

In order to enjoy the Scooby-Verse, you have to suspend a lot of disbelief. For starters, you have to accept that this gang of teenagers (each of whom has a permanent outfit) have nothing better to do than to drive around solving potentially paranormal mysteries. Secondly, you have to accept that they have a talking dog with a full-fledged personality and literally everyone is fine with that, even the people who don’t believe in ghosts. Finally, you have to accept that every ghoul they meet (for the most part) is a bitter person under a costume that is still somehow convincing enough to scare them.

The thing is, none of that was ever a problem in the animated Scooby-Doo shows and movies. They were aesthetically perfect for the show’s tone and borderline surreal quality. But that all came crashing down in the live-actions films (yes, plural. They made three after the hit 2002 entry), simply because of medium incompatibility. Everything that made the original so wonderful suddenly becomes a nightmare. The classic Hanna-Barbera theatricality, that I’d found endlessly endearing, becomes trite and boring. The monster designs that once struck a fine balance between comic and spooky (imagine hearing this damn laugh as a child) become parodies of themselves. Worst of all, Scooby-Doo, the glue holding the whole thing together, becomes a textbook case of the uncanny valley.

A similarly disastrous live-action adaptation of a popular animated work is M. Night Shyamalan’s astoundingly awful 2010 The Last Airbender, a film that simply seemed hell-bent on ruining everything that made the show the masterpiece it is. But again, I don’t think any amount of technique or craft could have saved this film. Yes, the CGI is a joke, the acting nauseating (even by child actor standards) and the whitewashing a borderline active attempt to sabotage the film, but at the end of the day, I honestly don’t believe that Avatar could’ve ever been a good live-action work.

I say this primarily because I believe that everything that made the original show the landmark it was is inherently tied to its mastery over animation as a medium as well as the conventions of adventure cartoons. For instance, one of the absolute finest achievements of the show was its brilliant blend of anime techniques with American cartoon sensibilities, creating a unique aesthetic that defies easy definition to this day. Such a feat could only have been possible through the use of animation, and the show’s world and characters would not have been as rich as they were without it.

Consider the wonderful animals of the Avatar world, with their hilarious, but clever designs, and endearing personalities. Whereas in the show, creatures like Apa and Momo proved delightful and enthralling additions to the story, their cinematic counterparts are simply hideous and odd. Again, this is no small part due to abysmal CGI and a generally piss-poor artistic vision, but I think it is also a matter of compatibility. The creatures seem absurd, almost grotesque, in live-action, but they make perfect sense in an animated world. It’s just easier to accept a flying bison and a winged lemur with quasi-human expression when they’re drawn.

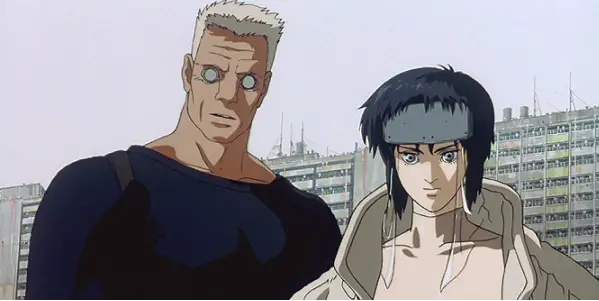

I could go on and on about what the film failed to translate from the show (e.g. don’t get me started on the fight choreo), but I’d rather fast-forward to the present, partially to get to my point, mainly to try and forget about The Last Airbender film. Earlier this year, we saw, not one, but two absolute failed attempts at anime adaptations: Rupert Sanders’ Ghost in the Shell and Adam Wingard’s Death Note. Both were widely criticized for their lazily patched plots, poor world-building, and, of course, whitewashing, but I don’t think enough has been said about the inherent problem of trying to adapt anime works to live-action films, especially American ones.

Leave Anime Alone

Anime’s incredibly rich set of conventions, in terms of both genres and style, has long been fertile ground for a plethora of phenomenal work. As with all animation, the best of anime utilizes every aspect of the medium to flesh out their stories and characters. This is, of course, not to mention that the finest anime also tends to be thematically rooted in its contemporary Japanese zeitgeist, drawing on pervasive issues and concerns from the national conversation. All this makes the task of adapting anime to live-action, specifically Hollywood live-action, inherently difficult, often impossible. But this begs another question, the one that I am most concerned with here: why is there even an impulse to adapt animation, whether American or Japanese, to live-action?

Let me clarify something first, before I start sounding like I believe in some kind of fixed orthodoxy of form: I believe in the narrative and thematic power of adaptation, especially the kind that is unconventional. Transforming a story from one medium to another can breathe new life into it, allowing us to view it in a completely new light. But there has to be a purpose behind the process of adaptation. Perhaps a novel has a cinematic quality to its narration that makes its story ideal for film. It’s worth noting that it tends to be much easier to adapt a work when its original medium is less technologically savvy than the medium it is being adapted into. This is why it’s extraordinarily difficult to make a decent videogame film. When a story is designed from scratch to be experienced interactively, redesigning it for film can be an insurmountable challenge, but one that is often worth a shot, if only to rework a compelling story into a more accessible form.

But why adapt a story into a medium it’s simply ill-suited for? This is why I think the films mentioned above were doomed, as is the forthcoming, already controversial, live-action adaptation of Katsuhiro Otomo’s groundbreaking Akira. There’s simply no need for stories that are so grounded in the styles and conventions of animation to be adapted to live-action, especially when doing so erases their cultural and thematic significance. Moreover, if directors wish to honor the animated works that have influenced their own vision, why not craft brand new stories that pay homage? Some of the finest American films of the past few decades have done just that: The Matrix borrowed from the original Ghost in the Shell, Inception from Paprika, Pacific Rim borrowed from a host of works, most prominently Mobile Suit Gundam, and Darren Aronofsky has borrowed extensively from Satoshi Kon’s filmography. This is not to mention Robert Zemeckis’s masterful ode to classic American animation, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?.

Conclusion

None of this is to say that filmmakers should under no circumstances take a stab at adapting animation to live-action. Recent films like Jon Favreau’s The Jungle Book and Bill Condon’s Beauty and the Beast, while far from perfect, are certainly enough proof that live-action adaptations of animation can be worthwhile. But it’s also worth noting that the animated films from which these two were adapted from were both adaptations themselves. i.e. their stories were not written from scratch for animation, making them much more susceptible to a live-action transition. When done right, an unexpected adaptation can be a true breath of fresh air. Hollywood just needs to pick its material better. And, for the love of God, stop trying to adapt anime.

Is there an animated film you’d like to see adapted into live-action?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Hazem Fahmy is a poet and critic from Cairo. He is an Honors graduate of Wesleyan University’s College of Letters where he studied literature, philosophy, history and film. His work has appeared, or is forthcoming in Apogee, HEArt, Mizna, and The Offing. In his spare time, Hazem writes about the Middle East and tries to come up with creative ways to mock Classicism. He makes videos occasionally.