A SERIOUS MAN At 10: A Prophetic Warning Against “Facts & Logic”

Danny Anderson teaches English at Mount Aloysius College in PA.…

The Coen Brothers have made a career of making mainstream movie audiences accept the weird and the quirky. Almost as remarkable as the quality of their films is the fact that they are also generally popular. Fargo, The Big Lebowski, and No Country For Old Men are each genuinely strange movies, and it is a considerable marvel that they each have dedicated popular fan bases. Even their less massively popular films, like Miller’s Crossing, have devoted fans beyond stuffy academia and #FilmTwitter.

Perhaps this enduring popularity is because their films very often have something to teach us. One of the Coens’ most puzzling efforts is 2009’s A Serious Man. As the film turns ten this October, it’s a good time to revisit the underrated gem and explore how prophetic it was in warning us against the spiritually corrosive influence of technocrats and their worldview.

A Serious Man Summary

A Serious Man is Joel and Ethan Coen’s most personal film in many ways, particularly with its deep engagement with the brothers’ Jewish heritage. Other films have broached the Coens’ Jewishness, such as The Big Lebowski and Miller’s Crossing, but none have so fully explored the faith and culture as this film.

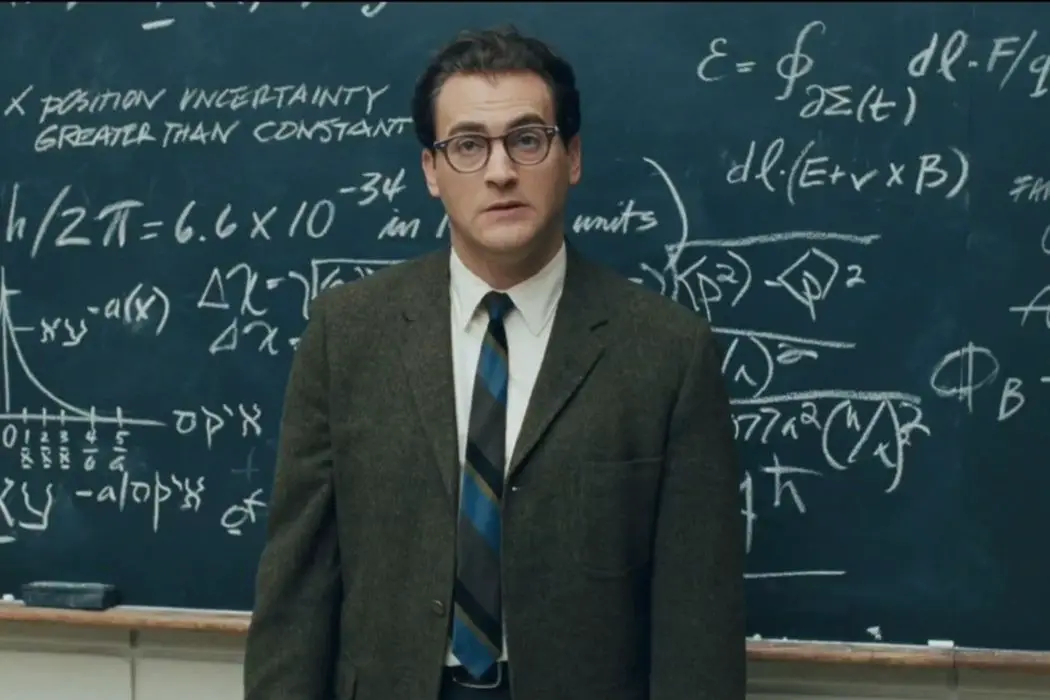

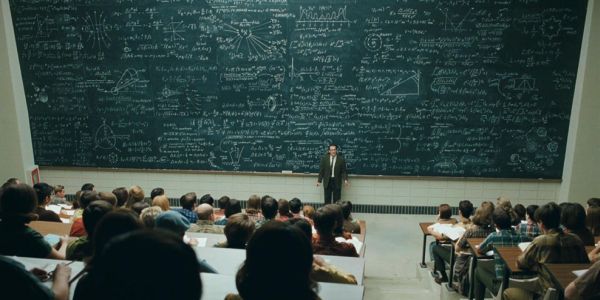

Set in the brothers’ home state of Minnesota in the 1960s, the film follows the Biblical plight of Job-like physics professor Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg) as his wife, Judith (Sari Lennick) has fallen in love with another man, a serious man, Sy Ableman (Fred Melamed). Added to this family tragedy is the trouble Larry is having at work with a Korean student, Clive (David Kang) who has seemingly tried to bribe Larry for a grade and thus has complicated his ability to achieve tenure. Added to all this is the legal and personal troubles of Larry’s brother Arthur (Richard Kind) for whom Larry carries a heartfelt fraternal responsibility.

The film narrates the plight of the deeply good, but overly-rational Larry as he seeks the wisdom of his faith in trying to make meaning out of the apparent meaninglessness of his suffering. The film is punctuated by his visits to three Rabbis, Rabbi Scott (Simon Helberg), Rabbi Nachter (George Wyner) and the ultimate sage, Rabbi Marshak (Alan Mandell).

And as if to boldly announce its intention to confound its main character, the film also seeks to confound its viewers by opening with an extended Yiddish-language folk tale, set in an ancient shtetl, about a possible dybbuk (played by Yiddish theater legend Fyvush Finkel). The mini-film has seemingly nothing to do with the plot of the movie and its presence instantly confounds the logical expectations of the audience.

“Accept The Mystery”

Larry enters a state of existential crisis because the logic of his life has broken down. His marriage has led to two children and a comfortable life in the suburbs, so when his wife informs him that she wants a “get,” a ritual divorce that would allow her to marry Sy Ableman with the blessing of the faith, he is shaken. His reaction is one of utter disbelief. And one gets the sense that Larry is as much disturbed by the illogic of the situation as he is the loss of his wife. As a logical man, he is angered by the violation of logos, not necessarily pathos. In short, he is unable to accept mystery as a part of life, and the Coens make the argument here that mystery is what ultimately makes life meaningful.

This theme is explored in intricate detail in Larry’s dealings with his foreign student, Clive. Larry meets with Clive to hear his complaint about a failing grade on a physics test. The student claims that his grade is unjust because he did not know he would be tested on the mathematics of Schrodinger’s Paradox. Clive insists that he understood the famous story of the cat and therefore understood the physics. Larry disagrees, stating that the story is unimportant and simply an illustration of the math, which is where the truth lies.

First of all, the very nature of this dispute is important. Mathematics work according to predictable rules, while stories are artworks that subvert the logic of predictability, often to moral ends (as this film does). Clive finds truth in the more abstract story, while for Larry it must exist only in the predictable math. Larry’s preference for the rational over the irrational is the source of his conflict with Clive, which ultimately threatens his tenure application. This is also the first moment where uncertainty is forced upon Larry, instigating his existential crisis.

Larry takes a phone call as Clive leaves and Larry soon notices an unmarked envelope full of money on his desk. There is no evidence that Clive left the money (and importantly, the film provides none to the audience either). The money appears as if by magic. This leaves Larry in an awkward ethical position, and he is also unable to reconcile the situation with his reliance on facts and logic, which only intensifies his personal angst.

Later, Larry has a confrontation with Clive’s father who doubles down on the ambiguity of the situation. The Korean parent puts the dispute down to a “culture clash,” and suggests that Larry’s claims about Clive’s possible bribe are defamation, and he will sue unless he changes the grade. The illogic of the bind rattles Larry’s brain. If he keeps the money but does not change the grade, he will be sued for theft. If he continues to claim that Clive left the money, he will be sued for defamation.

Larry, still seeking facts, tries to nail down whether Clive left the money. Clive’s father simply replies “accept the mystery.” Schrodinger’s Paradox is no longer theoretical; it works itself out in Larry’s life. Clive has both left the money and not left the money simultaneously.

The film constructs other moments to befuddle Larry, such as his dealings with Columbia Music, which employs a business model right out of Alice in Wonderland (you are sent an album when you don’t order it). The culmination of these events results in the film constantly punishing Larry for relying on his brain and neglecting the glorious mystery of the universe.

The Goy’s Teeth

Larry’s multiplying dilemmas lead him to seek the wisdom of his Jewish faith. This leads him to Rabbi Nachtner who tells him the story of “The Goy’s Teeth,” the centerpiece of the film and perhaps the most sublime achievement in the Coen Brothers’ filmography. It is a tightly-wound and exhilarating set piece that serves as a film-within-a-film, and it drives home Larry’s disconnect from the magic of mystery. It also presents the viewer with an object of awe and wonder, allowing us to experience something magical while offering no rational explanation for it.

The sequence begins with Larry explaining the recent events in his life and asking for the Rabbi’s help in interpreting them. Surely they must mean something. The ambiguity of Larry’s life circumstances frustrates his logical brain. Sensing his desperation, Nachtner proceeds to tell him the story of fellow congregation member Dr. Sussman (Michael Tezla), a dentist who has a magical experience at work.

In the mouth of a patient, a goy (or gentile) at that, Sussman finds letters from the Hebrew alphabet on the back of his teeth. Investigating further, Sussman interprets the letters as saying “Help me. Save me.” The telling of the story is thrilling, full of canted camera framing, shallow focus shots, and synchronized to a soundtrack of Jimi Hendrix as he tells of the many ways Sussman sought to find meaning in the experience. Here we see the Coens putting all their technical wizardry on display, but not in order to show off. Their purpose is to create a sublime object for Larry, and us, to be in awe of.

Finally, Nachtner ends the story with Sussman sitting in the very chair Larry sits in, asking “Tell me, Rabbi. What can such a sign…mean?” Nachtner intends to end the story here because the mystery and wonder of such unexplained events is the very point. But Larry still demands facts and answers. Puzzled by Larry’s demands, he simply states “We can’t know everything.”

Larry eventually coaxes some follow-up details about Sussman from Nachtner, but the wise Rabbi refuses to attempt an explanation or interpretation of the mystical happening for Larry. For the Rabbi, simply standing in awe in the presence of mystery is the point of the story. To draw rational conclusions or utilitarian knowledge from it is mere egotism and folly.

This is the lesson Larry never learns and, in the end, he is denied access to Rabbi Marshak, the story’s greatest sage. The privilege of his company is reserved for Larry’s son on the day of his Bar Mitzvah. Only the childlike, still capable of wonder, are welcomed into the presence of pure wisdom.

Conclusion: Resisting the “Facts And Logic” Regime

On its ten-year anniversary, A Serious Man should serve as a cautionary tale for our world today. In virtually all workplaces, assessment and efficiency drive all decisions. In education, STEM is king while “useless” degrees from the arts and humanities are mocked as naive and indulgent. The New Atheism, the Intellectual Dark Web, and “Sober and Serious” political punditry boastfully prize “facts and logic” as the source of wisdom and importance, mocking emotion along the way.

Likewise, social media demands immediate responses to world events, and we all must be ready with our opinions and hot takes. Our “serious men” are people like Nate Silver with his data analytics. The Coens, however, offer an entirely different image of wisdom and the “serious man.”

A Serious Man coalesces many of our current cultural values and traits into the character of Larry Gopnik, and it ruthlessly, though humanely, punishes him for them. He has replaced wisdom with facts and his insistence on rationality and utility in knowledge is his undoing. Ten years later, our own misplaced intellect has proven to be ours as well. Now is a good time for all of us to simply accept the mystery.

What are your favorite Coen Brothers movies? Let us know in the comments below!

Watch A Serious Man

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Danny Anderson teaches English at Mount Aloysius College in PA. He tries to help his students experience the world through art. In his own attempts to do this, he likes to write about movies and culture, and he produces and hosts the Sectarian Review Podcast so he can talk to more folks about such things. You can find him on Twitter at. @DannyPAnderson.