A GERMAN YOUTH: Revisiting The Past For The Sake Of The Future

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster,…

The line between activist and terrorist can be dangerously thin and, depending on your beliefs, easily twisted to suit a particular agenda. Today, all you have to do is turn on Fox News and see pundits haranguing antifa as a terrorist organization to realize that perception is almost as powerful as action when it comes to the labels assigned to the politically active.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s in West Germany, a group of student activists wanted to withdraw from the Vietnam War, end nuclear proliferation, and rid their government of the bourgeois capitalist cabal that held the power. Indeed, West Germany’s political and economic leaders included many who were members of the Nazi party under the Third Reich and seemingly saw no punishment for their wartime actions.

It’s understandable that these young people would want to confront their country’s past and radically change its present for the sake of creating a better future. However, their evolution from activists to terrorists — first in perception, thanks to the police, politicians, and media, and then in action — is what is primarily remembered from that time period.

Jean-Gabriel Périot’s documentary A German Youth chronicles the political radicalization of the group that became known as the Red Army Faction. Périot’s film is entirely constructed from preexisting visuals and sound from the period, including films made by the RAF (some of whom met at Berlin’s film academy), television interviews, news broadcasts, courtroom recordings and much more. The result is compelling collage as historical artifact, presenting the old as something altogether new so that we can see it — and the RAF — in a different light, and apply lessons from that time to our own today.

The Red Flag

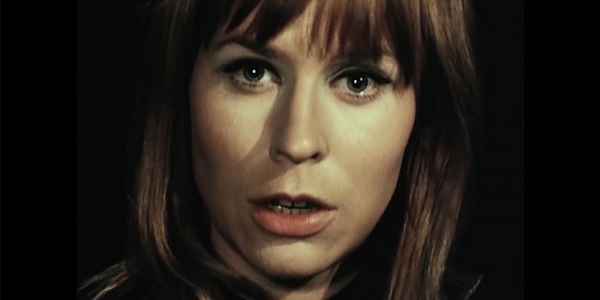

Some of the most compelling footage in A German Youth consists of television interviews featuring Ulrike Meinhof, a leftist journalist who is often not only the token socialist invited to espouse her views in these roundtable discussions, but also the token woman. To watch her opine eloquently on her beliefs on television surrounded by stern men who all appear to be twice her age contrasts starkly with the Ulrike Meinhof we have been trained to remember, the one who helped break Andreas Baader out of police custody, went on the run, and eventually died under mysterious circumstances in prison.

What changed the Ulrike Meinhof from those early television segments into the Ulrike Meinhof who became so synonymous with the Red Army Faction that the group’s unofficial moniker was the Baader Meinhof Group? Her beliefs did not change, but the means she used to express them did. After all, Meinhof and others did not turn immediately to violence. They wrote articles, distributed leaflets, made experimental films and organized peaceful protests. Yet throughout A German Youth, we see how they were up against a police state that wasn’t shy about using violence to counter them, a right-wing news media led by the powerful Axel Springer that used the numerous publications and programs at their disposal to broadcast a one-sided narrative that slandered them (sound familiar?), and canny politicians that, if they could survive the process of deNazification, were definitely not going to be easily disposed of by a group of angry young people.

How to Make a Molotov Cocktail

The West German student movement collapsed in 1968, and from there, events took a more extreme turn. Now, is turning to violence in order to get the powers that be to pay attention to your message the right method? Is bombing department stores and army barracks the best way to show your opposition to capitalism and imperialism? It’s easy to sympathize with the beliefs of the RAF, and to empathize with their treatment at the hands of the powerful in the early days of their movement; it becomes harder to do so as the body count rises.

And yet, the first blood of their movement was not on their hands, but that of the police. A German Youth reminds us of this by showing us the literal footage of the march where a young activist, Benno Ohnesorg, was shot in the head by the police and left for dead. By assembling the footage relatively chronologically, one is able to see the natural progression of how the RAF were radicalized, and why they stopped writing articles and started building bombs — whether you agree with those actions or not.

A German Youth concludes with footage taken from one of my favorite movies about this time period. Fittingly, it’s another cinematic collage of sorts: Germany in Autumn, an anthology film examining the period of time in 1977 that began with the RAF kidnapping a prominent industrialist and ended not only with his death, but the deaths of several RAF leaders in prison. Périot ends his film with footage from Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s segment, in which Fassbinder aggressively quizzes his mother about what kind of government she would prefer for Germany. Finally, Fassbinder’s mother admits she wouldn’t mind another authoritarian leader, as long as it was a fair and just one.

This scene perfectly encapsulates the differences between the generations in Germany — those who survived the war, and those who came after it — and their approaches to how the country should be governed. Decades have passed since, and yet these differences still remain, not just in Germany but in countries around the world.

A German Youth: Conclusion

A German Youth presents the historical evidence and leaves the audience to form their own opinions and draw their own conclusions about how and why the Red Army Faction came to be and how and why they should be remembered. The answer differs depending on who you are and what beliefs you hold, and needless to say, it is not a simple one. And while A German Youth does not ask us to side with Andreas Baader, Ulrike Meinhof, Gudrun Ensslin, Holger Meins and the rest of the RAF, it does want us to understand them, and to learn from them. Needless to say, in our current political climate, it’s a history lesson worth repeating.

What do you think? Do documentaries composed entirely of archival footage sound appealing to you? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

A German Youth was released in the U.S. on October 11, 2019. You can find more international release dates here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Lee Jutton has directed short films starring a killer toaster, a killer Christmas tree, and a not-killer leopard. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Film School Rejects, Bitch: A Feminist Response to Pop Culture, Bitch Flicks, TV Fanatic, and Just Press Play. When not watching, making, or writing about films, she can usually be found on Twitter obsessing over soccer, BTS, and her cat.