Welcome to A Century in Cinema, the monthly column where I’ll be discussing films from a hundred years ago, the historical impact they had, and how they hold up today. Whether we’re covering timeless classics or obscure gems, follow along as we continue to explore…a century in cinema! WARNING: Hundred-Year-Old SPOILERS ahead!

“The blood of America is the blood of pioneers.”

Since the very early days of cinema, from Edison Studios’ shorts and Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery (1903), Westerns have been a part of the fabric of film history. Though the genre has experienced varying degrees of popularity, through the silent era they were a fan favorite, including today’s focus, James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon (1923). It was the year’s second-highest box office earner of the year, under The Ten Commandments, and a personal favorite of President Warren G. Harding. With its shots of the vast Western landscapes and tributes to the generation that braved the new frontier, it’s hard not to understand the appeal of this Western adventure.

New Frontier, New Romance

The film opens in Westport Landing, now Kansas City, in May 1848. A caravan, led by Jesse Wingate (Charles Ogle) and his family, prepare to continue west toward Oregon. Some want to leave without the wagons from Liberty, Missouri, which are bringing up the rear and led by Will Banion (J. Warren Kerrigan), a Mexican War veteran and his rough-talking companion William Jackson (Ernest Torrence). Meanwhile, a group of Natives are concerned with the white men bringing their plows, or “monster weapons,” that will bury the buffalo and uproot the forest. So, they must die. Back at the camp, Banion meets Jesse, his wife (Ethel Wales), their daughter Molly (Lois Wilson), and her fiancé Sam Woodhull (Alan Hale). Sam wants to get married here in Westport, but she wants to wait.

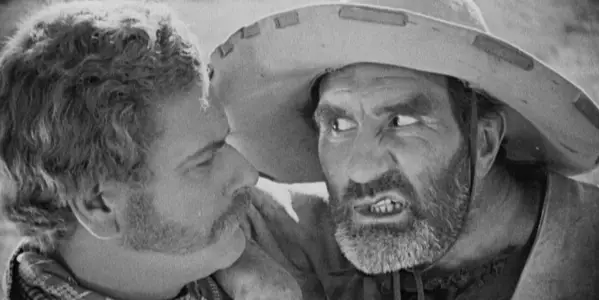

The two groups travel at a grueling pace. Folks are weary and discouraged, with some even turning back and heading home. Molly and Banion become closer, to Sam’s distaste, so he informs Jesse that Banion was kicked out of the Army for stealing cattle. Incensed, Jesse tells Banion to stay away from his daughter, which he does. They arrive at the north fork of the river, where a small band of friendly Native Americans run a ferry across charging ten dollars per wagon (about $388 today). Rather than pay, Sam wants to cross the river, but Banion suggests they continue on to a safer spot before attempting it. This leads to the two finally duking it out, “knuckle and skull,” but Sam suggests making the fight no holds barred. Banion gets the upper hand and rejects the opportunity to gouge Sam’s eyes out, despite the crowd’s urging, but Molly deems him a brute for even considering it. At Jesse’s suggestion, Banion takes his caravan and they go their separate ways as Sam ferries out to scout across the river. When he gets across, he refuses to pay the Indigenous people and shoots one. Some of the Wingate group manages to cross the river, but with a staggering loss of wagons and stock. Meanwhile, the mountain man Jim Bridger (Tully Marshall) crosses paths with the Banion train and asks to join them for a while.

By early autumn, the caravans reach Wyoming only a few miles apart. Running out of food, the men hunt for buffalo. In the commotion, a man falls into a bog. William pulls him out but tries to throw him back when he realizes it’s Sam before Banion stops him. In October, Banion’s caravan arrives at Fort Bridger, the Wingates not far behind, where Jim introduces them to his two Native wives, Blast Yore Hide and Dang Yore Eyes (because she’s younger and prettier, you see). Jim has a drink with Joe Dunstan, an Army man who tells him about gold found in California. He also has news about Banion’s Army trouble (which a lawyer named Abe Lincoln is dealing with): Banion has been reinstated! However, by the time Jim finds Banion to tell him, he’s so drunk he forgets the message. Instead, he tells him about the gold and suggests he go to California instead of Oregon. When the Wingates arrive, Sam declares he wants to marry Molly here, and Banion takes off with his caravan to California.

As the Wingate camp prepares to celebrate the upcoming wedding, Jim tells Molly not to marry Sam until he can get drunk enough to remember what he needs to tell her. Eventually, he remembers and tells her about Banion’s reinstatement. She immediately tells Sam they’ve misjudged Will and that she’s going to him, just as she’s struck with an arrow. Panic ensues as they circle the wagons for protection. Jim believes they won’t attack until daybreak. Sam tells Jesse to send for Banion, but Jesse says no man could get through the barricade. Hearing this, Jesse’s little son Jed takes off. As predicted, at daybreak the Natives charge the camp. It’s a massive scene, with bullets and arrows flying from both sides and wagons being set on fire. White men take cover behind wagons and piles of lumber and Natives shoot from cliffs above. Mrs. Wingate hides in a wagon with Molly, who’s out of it but still holding out hope Banion will save her. Just then, Jed rides back in with Banion and his men to the rescue. After the dust settles, he asks to see Molly. Jesse refuses because of her promise to Sam to never see Banion again, not knowing of her plans to see him before the battle. He leaves once again for California.

After being delayed for weeks, the wagons are now troubled with the first snowfall. William, having stayed with Jim until he recovered, leaves for California and asks if Molly has a message for Banion. Tears in her eyes, she says to tell him she’ll be waiting for him in Oregon. Hundreds of miles out, the caravan finds a signpost splitting the trail to California or Oregon. Most of the men are divided on which way to go, with Jesse vying for Oregon. Sam decides to lead men to California, accepting he’ll never marry Molly and on the lookout for Banion. Those leaving with Sam discard their plows on the side of the trail, sacrificing the tool needed to cultivate land in search of greed. Months pass as the Wingate caravan makes their way to Oregon. As soon as they arrive, Jesse puts his plow in the snow to break ground and leads everyone in prayer.

In the spring of ‘49, William arrives in California. He asks around to find Banion’s cabin, learning that someone else asked about him today. Williams finds him panning for gold and gives him Molly’s message. At that moment, Sam arrives at the cabin, rifle in hand. He throws a rock at the door to lure Banion out and takes aim, but William shoots him first. Out in Oregon, Molly is at the family cabin when Banion arrives on horseback. Mr. and Mrs. Wingate look on as the two finally kiss.

Uncovering An Audience Pleasing Adventure

The Covered Wagon was a massive production for its time. It had an estimated budget of $782,000 (over $14 million today), and Joe Franklin, in his book Classics of the Silent Screen, deemed it “the first American epic not directed by Griffith.” Production took place across California, Nevada, and Utah, where the buffalo sequence was shot. However, as buffalo had been nearly hunted to extinction only a few decades prior, it was difficult to acquire a large herd for the sequence. To bolster the numbers for some shots, small lead castings were made that were pulled on chains with forced perspective to give the appearance of running.

Rather than building replicas, Paramount acquired real wagons that brought pioneers out west, still owned by families and their descendants. Most of the extras in the film are the families driving and living out of their wagons, just as they did all those years ago. In addition to actual pioneers, Native tribes in the area were recruited for filming, such as the Northern Arapaho in Wyoming. A member of the production team, Tim McCoy, was the only person who could speak to the Arapahos, leading to him becoming the film’s technical advisor.

The film premiered in New York City, and though this was before the era of fully synchronized sound in film, a musical soundtrack was recorded using the short-lived DeForest Phonofilm process, recording sound directly onto the film. Sources vary on whether this record soundtrack was for the whole film or only two reels’ worth, but the Phonofilm version was only shown this way at the premiere at the Rivoli Theater.

Conclusion:

Watching this film today, it’s easy to see why this film would have been such a hit. For the older generations, the shots of dozens of wagons trekking across the Midwest and the hope for the future juxtaposed with the harsh conditions endured to get there may be a familiar memory. That, blended with a tale of romance and the large action sequences reminiscent of the Wild West vaudeville shows popular at the time all but guaranteed Paramount a hit. The recurring use of plows throughout the film, likely intended as a metaphor for settlement, comfort, and forging one’s path, as well as the repeated use of “Oh! Susanna” as optimistic Americana, fortifies a story of the grit and determination needed to start a new life across the country.

While the film isn’t perfect, and its depiction of Jim Bridger as a drunk bigamist was so inaccurate that his daughter attempted to take the studio to court, there is a lot to enjoy. Diehard Western fans will find it worth their time, but for the casual film fan there may be more enjoyable films from this year to check out.

Watch The Covered Wagon

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.