A Century In Cinema: THE TEN COMMANDMENTS (1923)

Jules Caldeira is an Associate Editor for Film Inquiry based…

Welcome to A Century In Cinema, the monthly column where I’ll be discussing films from a hundred years ago, the historical impact they had, and how they hold up today. Whether we’re covering timeless classics or obscure gems, follow along as we continue to explore…a century in cinema! WARNING: Hundred-Year-Old SPOILERS ahead!

Nearly seventy-five years ago, through the 1950’s onward, Hollywood began their push of epic movies, specifically historical and Biblical films. Cleopatra, Ben-Hur (both versions), The Ten Commandments, and others were released – often to great fanfare, high box-office numbers, and critical accolades – in the hopes of luring audiences away from their small, black-and-white television sets and showing them how big, bold, and colorful cinema could be by comparison. For a couple decades this worked, and while epics are still made today, some are awarded the same reception as films of the past (Braveheart, Titanic) and others (Noah, Exodus: Gods and Kings) did not have the same domestic or critical success, yet still did well overseas.

However, the fifties were not the decade of origin for these types of films; in fact, epics are almost as old as cinema itself. From Metropolis, Dr. Mabuse the Gambler, and the French film La Roue, recently presented in its seven-hour glory, to The Birth of a Nation (only mentioned for its historical context, not its repugnant content), and even today’s film, 1923’s The Ten Commandments. Prior to Cecil B. Demille’s 1956 depiction of the tale of Exodus in VistaVision, he produced a silent version that differed in a number of ways from its successor, yet still managed to grip the audiences of the day. The film topped the year’s box-office list, accruing $4.1 million in total, over $600,000 more than the number-two film, The Covered Wagon, another Paramount picture.

A Black-and-White Biblical (Double) Feature

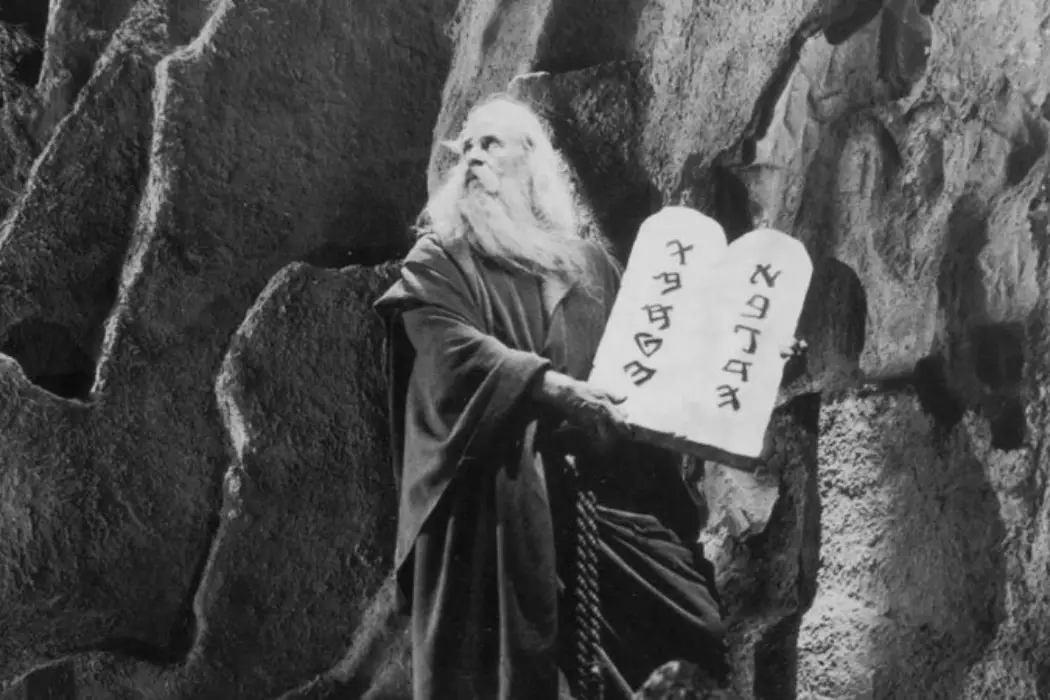

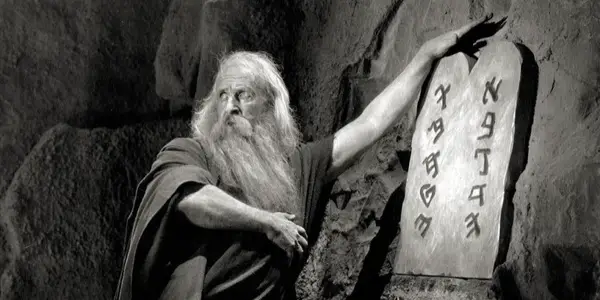

In contrast to the 1956 film, here DeMille and screenwriter Jeanie MacPherson chose an interesting story structure: a film in two parts, each distinct from the other and only linked by the Commandments themselves. After the opening credits, title cards describe a world that laughs “at the Ten Commandments as old fashioned” until the horrors of World War I left “a bitter, blood-drenched world” crying “for a way out.” What could it be? The Ten Commandments, of course! The heavy-handed Christian message is pervasive throughout, to be expected, and sets not only the precedent for DeMille’s introduction to his later remake, but also sets the tone for the reverence and sincerity he takes with this subject matter. The first half is the Prologue, chronicling Moses (Theodore Roberts) releasing the Israelites from slavery under the Pharaoh Rameses (Charles De Rochefort, billed as De Roche), beginning after the ninth plague has struck Egypt.

To avoid rehashing the oft-told tale, suffice it to say the Prologue checks all the boxes. Highlights include the parting of the Red Sea (for which gelatin was melted and the footage combined for an impressive effect) and Moses receiving the Ten Commandments seemingly by fireworks in the sky literally spelling it out for him, finally culminating in his summoning the power of God to strike down the false idol – a golden calf – with lightning. As with its successor, this film makes great use of special effects, stunning sets and costumes, with armies of extras to make the story feel truly epic. Had this been an independent featurette, it would be engaging and entertaining on its own, and yet there’s still another half to come.

The next half, known as the Story, contrasts with the Prologue by unfolding in a modern setting and is an original script rather than an adaptation. Though not a Biblical story, it’s just as overt in its themes, focusing on a family living by the Commandments, and the consequences that befall those who renounce them. We meet the McTavish family: the mother Martha (Edythe Chapman), a Christian fiercely devout almost to a fault, and her two sons John (Richard Dix) and Dan (Rod La Rocque). While John follows the ways of his mother, even working as a carpenter, Dan is an atheist who openly mocks their beliefs. After being confronted by his mother, Dan refuses to apologize to God, as he doesn’t believe in one, leading her to hold the door wide open for him to leave. He then dines at a lunch wagon while a starving Mary Leigh (Leatrice Joy) searches for food outside. Caught stealing Dan’s sandwich, he chases her through the street. Conveniently, she takes refuge in John’s carpentry shop attached to the house. He convinces Martha to let Mary stay the night. When Dan returns, John also manages to get him to set aside his issues with their mother and introduces him to Mary. Charming as he is, Dan wins her over and the three get along swimmingly.

Later, Dan and Mary dance and play records on Sunday, the Sabbath. He confides in her that he’s crazy about her, but hasn’t the nerve to speak further. Meanwhile, John watches from afar as he eyes a diamond ring meant for Mary. He calls her over, gifting a bouquet, and tells her that they’re “from a man that’s crazy about [her] – but hasn’t got the nerve to speak,” a man who wants to marry her, but isn’t sure if she feels the same. Mistaking his words to be from Dan, Mary professes her admiration, to which John produces the ring. She’s surprised Dan didn’t give it to her himself, which crushes John, but he quickly sacrifices his happiness for theirs, and the two become engaged. Martha, upset from the noise and dancing on such a holy day, chides the two for breaking the fourth Commandment. The tension leads to her breaking the record, and John sticks up for them, but Dan and Mary decide to run away and live in their “own heathen way.”

Three years later, Dan’s heathen lifestyle has worked out for him. He’s become a wealthy contractor that makes most of his profits from using subpar material and cutting concrete with sand and jute. With a contract to build a cathedral, Dan employs John to be the head contractor, given his high moral standing would lend the project some legitimacy. He also has an affair with a woman, Sally, as if he wasn’t heathen enough already. One day, Mary visits the site and talks to John, slipping on a stone that easily breaks, leading him to realize the whole building is unsafe. He calls for the workers to clear the cathedral, not knowing Martha has also visited to see her sons’ work and insisted she could go inside. Tragically, a wall collapses on her, and when she’s dug out of the rubble her last words to Dan are words of regret for teaching him to fear God and not focusing on His love.

Broke and disgraced, Dan learns that a tabloid is preparing to expose his misdeeds. His partner suggests bribing the reporter, but he doesn’t have the money. Failing a suicide attempt, Dan returns to his mistress, asking for her to return a set of pearls he gave her. She refuses, showing him a newspaper article about a woman who fled the leper colony of Molokai and came to the United States. revealing it to be her, who came over hidden in bales of jute, which he had used to cut his concrete, she tells him she also infected him with leprosy. In a rage, he shoots her and attempts to flee to Mexico on a motorboat, naturally named Defiance. Enduring rough waves and weather, he ends up off-course and crashes into the rocks, where his body is seen on shore. Back home, Mary fears that she’s been infected with leprosy and stops to bid John goodbye before fleeing. Rather than letting her go, he brings her in and reads the story of Jesus healing the lepers as a reenactment takes place on-screen, though only showing Jesus from behind. At that moment, Mary can clearly see in the light that it’s gone, which John reiterates as a clear metaphor for the healing light of Christ.

An Engaging Exodus With a Lasting Legacy

While DeMille directed a number of films before this, The Ten Commandments would be his first epic feature film, pulling out all the stops in terms of production, from sets larger than those of D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance to the two-strip Technicolor technique used for some of the Prologue, particularly during the Exodus. Regrettably, these sequences are completely in black and white for the “restored” version. Though it dominated the box office upon release, and indeed held Paramount’s record for 25 years until it was broken by DeMille himself once again, the critics were at times ambivalent. The Prologue was consistently praised, but it was the latter half that seemed to disappoint. According to Variety at the time, the Prologue scenes “are immense and stupendous, so big the modern tale… after that seems puny,” and a “simile might be to start your car in high, take it out of gear and allow it to run down. That’s ‘The Ten Commandments.’”

Viewing this film a century later, the critics weren’t wrong. Both halves of the film are great in their own way. However, having a large-scale Biblical story juxtaposed against a contemporary morality tale, though linked thematically, does feel like they could have been released separately and done just as well. As mentioned above, the Prologue is stunning, even by modern standards, in terms of sheer scope. In fact, the sets, which were built in the Guadalupe Dunes 170 miles north of Los Angeles, were so massive that DeMille didn’t even try to haul them back. Instead, he had them bulldozed and buried in the sand, abandoned. Over the decades, numerous excavations have been attempted to recover these sets, now considered an official archaeological site, some of which is documented on an episode of National Geographic’s Drain the Oceans and the feature-length documentary The Lost City of Cecil B. DeMille. Though the Story half of the film does seem as though it’s missing the budget of the Prologue, and the never-subtle message may feel a bit much for those who don’t subscribe to the beliefs, it’s still very engaging once it gets going. After Dan becomes a contractor, his story of hubris and the perils of blind greed is fascinatingly tragic. While it seems almost too much for one man to endure, it nonetheless hammers home DeMille’s intention to show the consequences of flouting the Commandments and ties both halves of the film together.

Conclusion

For fans of epic films, particularly the 1956 remake of this one, the 1923 version is worth a watch. Whether it’s to compare the two (some scenes are said by DeMille historian Katherine Orrison to have been recreated shot-for-shot, and the advancement of special effects is quite interesting), to witness a piece of Old Hollywood history that’s quite literally still being rediscovered, or because the film speaks to your faith, there’s a little something here for many types of audiences.

The Ten Commandments is available to stream on YouTube, Tubi, Kanopy, or Public Domain Movies, and can also be rented or purchased through most VOD services. It can also be found on the 50th anniversary release of the 1956 film’s DVD and Blu-Ray copies.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C-rmEWYZpa8

Watch The Ten Commandments

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Jules Caldeira is an Associate Editor for Film Inquiry based in Sacramento, CA. He's a drummer, part-time screenwriter, and full-time Disney history nerd who can be found on social media when he remembers to post, and can be contacted at [email protected].