CHILDREN IN WAR: A Documentary for Our Times

Brian Walter is a college professor by day and a…

The images are horrifying.

Children playing in the rubble of blasted-out buildings. Children are under the threat of sniper fire trying to retrieve water in plastic containers to take back to their families. Children showing their scars and their amputations to the camera but saying they were lucky, because they could have been killed outright.

These images are from Alan and Susan Raymond’s gentle but outraged 1999 documentary, Children in War. Focusing on then-recent conflicts in four different regions – the former Yugoslavia, Gaza and Israel, Rwanda, and Northern Ireland – the film examines the rise of warfare that targets not only civilian populations but specifically children.

If innocence used to be the first casualty of war, it is now actual innocents who are the primary casualties of war. The consequences of this brazen shift have only grown more unspeakable in the quarter-century since the filmmakers called attention to it.

What makes a viewing of this film so instructive in 2024 is to realize that it was made before social media had taken over the Internet. Google barely existed, and there was no Facebook, no TikTok, no TwitterX. Trolls were still fairy tale creatures, not AI bots generated by the literal millions to harass dissent and drown out anyone brave enough to challenge entrenched corruption.

As strident and heedless as it has always been, politics had not yet been reduced to a 24-7 propaganda barrage designed to divide and conquer all human discourse into Us vs. Them factions relentlessly at each other’s throats.

So Children in War was free to ignore all partisan considerations and just depict war as hell, a moral failing that shames us all. The film shows how children are recruited by political and military forces that exploit their pain, their grief, and their losses to propagate hate across generations and to plant the seeds for more and more and more violence.

Innocence, as Children in War shows, is also the first resource – the all too-perfect fuel – for endless war.

Refreshing and Wrenching

Children in War also shows how filmmaking can be simultaneously bold and restrained, both polemical and compellingly reasonable.

Documentary, according to one definition, is a “motion picture that shapes and interprets factual material for purposes of education or entertainment” (Britannica). What makes Children in War as refreshing as it is wrenching to watch even today is its resolute aim simply to drive home forever the universal wrongness of war.

The narrative approach is simple. At the beginning of each of the four segments, co-director Susan Raymond in voiceover provides some historical background for the conflict and then gently puts direct questions to the children survivors about their experiences.

Raymond is never shown on screen, but her subdued tone and carefully framed questions are woven into the fabric of the film, helping the children give voice to the ineffable and the viewer to connect all the more deeply with their anguish.

The children include both Palestinian teenagers and Israeli settler teenagers in Gaza and the West Bank vowing never to leave, an eleven-year-old whose father was imprisoned for plotting to commit murder in Northern Ireland, and a five-year-old in Rwanda who was left for dead after her family was killed before her eyes.

Most appear onscreen for no more than a few minutes, but their faces and their voices as they respond so openly to the heartbreaking questions are unforgettable.

Both captured and archival footage provides further context for the children’s accounts. Some of the shots are especially harrowing, including actual footage of civilians being cut down by sniper fire and, in a distant framing, machete murders in Rwanda committed by the Hutu majority against the Tutsi minority.

Innocence over Experience

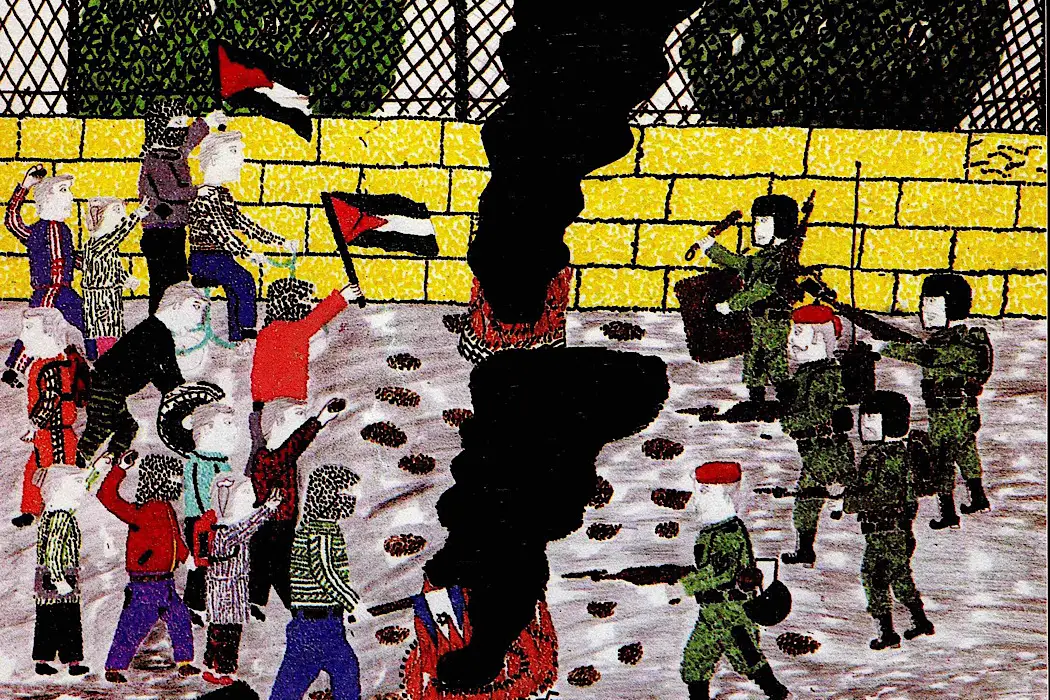

But perhaps the most effective imagery is the children’s own artwork, some of it made as part of art therapy classes designed to help them cope with the atrocities they have been forced to witness and endure.

It would be hard to overstate the power of these naïve depictions. To see tanks and bombs and bayonets rendered in the thick crayon-lines and broad-brushed watercolors of children’s art is to experience an almost irresolvable cognitive and moral dissonance.

Such innocent art is, in its very form, a rejection of the carefully contrived, superficially sophisticated rationales for war, the pretexts that are tortured into existence to underwrite elaborate regimes of cruelty and violence. Children’s artwork is, in its directness, a natural opposite to the machinations of power, its innate incompatibility making the almost unimaginable violence it depicts all the more irredeemable and obscene.

When adults look at children’s drawings, it’s tempting to fill in what we see as gaps, to smile at the innocent imagination’s attempt to depict realities that we convince ourselves to see as more complex than the young can appreciate.

But looking at these paintings and drawings reverses the process, disarming the impulse to provide explanatory context, leaving us with an unbearably stark image of the inexpressible violence that has been inflicted on these children. Innocence overtakes and reclaims authority from experience in these drawings.

Moral Imagination

By providing a cinematic forum for the voices and visions of these survivor children, Alan and Susan Raymond venture into the deepest and darkest of human-created abysses to reopen space for moral imagination – the crucial ability to relate to others not as obstacles or resources, but as vital human subjects endowed innately with all the same rights that we claim for ourselves.

That is no small feat for the filmmakers, no matter how mindfully they approach their task. Strangers who show up in the aftermath of tragedy with a camera and a microphone, the Raymonds never overstride the voices or indelible faces of their vulnerable subjects. The respect that they show to these children makes for perhaps the ultimate cinematic repudiation of war, cruelty, and violence.

Grace Notes

For students of the medium, the editing of this film makes particularly rewarding (if sobering) study. When do you cut away from a child who has just described the death of their father or their best friend? How long should you let the camera linger to give their pain its full weight without seeming exploitative?

So too do the soundtrack choices. If Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” seems inevitable, note the careful timing of its introduction, the violins starting up just as an ambulance appears on screen in Sarajevo, followed by a seven-year-old child lying in a pool of his own blood, already beyond the reach of medical care. The music carries the grief, allowing it both to circulate and to pass through, a catharsis that does not reduce or euphemize.

Note also the somber but beautiful choral number that plays over the beginning of the Rwanda segment, at the time, the first UN-certified genocide since the Shoah of World War II. These and the other musical selections quietly but consistently enhance the arresting effect of the children’s testimonies.

Finally among these grace notes, the interviews and tableaux that end each of the four segments are superbly chosen. The Gaza/Israel section ends with the funeral of a 14-year-old, killed when her bus was bombed in Jerusalem.

Her close friend, recorded in close profile in the midst of her fellow mourners, weeps throughout but determinedly delivers her tribute, her wrenching good-bye giving way to the kaddish and a slow fade-out, all of it accompanied unobtrusively by Ravel’s “Pavane pour une enfant défunt” on solo piano.

“They did it for nothing.”

But the segment capper that perhaps resonates the longest is the five-year-old in Rwanda who was left for dead after seeing her parents cut down before her eyes. She was left for dead because she too was hacked with a machete. She touches the long scars on her head as she explains that the attackers killed her parents and then killed her.

When asked why they did it, the child thinks for a moment, the background noise subtly draining away to silence. Then she responds, “They did it for nothing.” Fade to black.

The film world has offered us many moving depictions of war over the 130 years or so of its existence. What Children in War contributes to the long history of this genre is a clear-eyed, disciplined, and eloquently forceful rejection of every lie and every excuse ever conjured for the justification of war.

Children in War is available for VOD streaming.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Brian Walter is a college professor by day and a hopelessly sleepy college professor by night. His work has appeared in a variety of literary and film studies publications, and he appears as an 'old coot' interviewer with a magic camera in the final chapter of Donald Harington's final novel, "Enduring." He lives a short walk from the St. Louis Zoo with his remarkably patient, loving wife and a quirky assortment of canine and feline familiars.