3D: A New Dimension Of Apathy?

Graduate of the University of Portsmouth with a first class…

“My approach to 3D is in a way quite conservative … I want it to be comfortable. I want you to forget after a few minutes that you are really watching 3D and just have it operate at a subliminal, subconscious level. That’s the key to great 3D and it makes the audience feel like real participants in what’s going on.” (source)

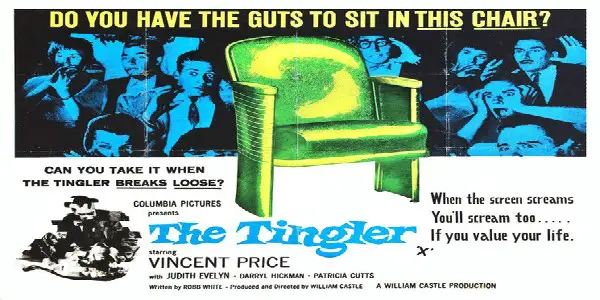

Straight from the horse’s mouth, so to speak, that 2009 quote from acclaimed Avatar director James Cameron, a ‘call to arms’ regarding the new wave of RealD films, framed a period of cautious excitement about the implementation of this radical new technology. Cameron’s sci-fi epic was set to break down all barriers and propel cinematic 3D back into the mainstream. A grand statement, yes. One that was set to frame either 3D’s meteoric rise as the future of the cinema industry, or resignation to laying amongst The Tingler, Cinerama, and Duo-Vision in the abandoned graveyard of long-forgotten movie fads.

Six years on, and 3D has stayed the course. It still may not be the saving grace of the film industry, but it is certainly no Tingler. From its roots as a cinematic sideshow, 3D is now just as commonplace in the film industry as CGI, stunt doubles, and pampered prima donnas. Rarely, now, is a tentpole blockbuster or animated family film brought into production without a 3D format option attached. The technology simply dominates the mainstream film releases: from the Marvel Cinematic Universe, to Pixar and Dreamworks, and even the reinvention of George Miller’s once notoriously low-tech Mad Max franchise.

Rightly or wrongly, the ‘fad’ period is over, and 3D is here to stay. Quite clearly, the question is not in its financial viability (with six of the ten highest grossing films owing much to the monetary ‘shot in the arm’ that a 3D upgrade presents), but in its artistic and crowd-pleasing merits. Indeed, the real debate lies not in how successful 3D has been for the studios, but in whether film fans are truly engaging with the technology, or whether its continued resurgence is down purely to market saturation and studio greed. Are we forking out extra through sheer reluctance and a lack of any real choice? Or does 3D indeed bring that little extra wow factor to the auditorium? Are we simply apathetic?

Swap those cheap plastic 3D specs for a nice pair of gold-rimmed reading glasses and ponder no further, as I take you through all aspects of the debate.

Money, money, money

Gone were the days of It Came from Outer Space and all its corny, crowd-pandering ‘pop out’ visuals – 3D was now going to be a stunning and integral new storytelling tool for the world’s foremost directors to tinker with. At least, that was the selling point. If nothing else, the overwhelming success of Avatar proved that the public were certainly ready to jump on board with such ideals.

Wild, unprecedented speculation it may be, but without the 3D sideshow, Avatar’s final box office gross of $2.8 billion begins to look completely unattainable for a bizarre naturist think piece featuring a clan of overgrown Smurfs. Avatar was an event movie in its truest sense, and RealD was the name in bright lights on the marquee.

Not that the film was the first to drink from the 3D well, of course, but with little fanfare reserved for the 3D upgrade of precursors such as Journey to the Centre of the Earth, Bolt, My Bloody Valentine, and even Up, Cameron’s passion piece became the film that broke the two-dimensional ice.

Before long, every major studio was churning out 3D films, and every theatre wanted RealD projectors to keep up with the demand. In the twelve months following Avatar’s release, there were upwards of twenty-five notable 3D releases. In the previous year, less than ten.

In an era of online streaming, illegal downloading, and home entertainment sales, 3D technology became an important weapon in drawing the crowds back to the multiplex. Its inception was as much about protecting against revenue loss as it was revenue boosting, and the figures prove its success.

So what’s the problem?

So 3D is a wonderful way for the richest studios to stay in the money. Joy. But what of the everyday film fans? What of the cinemas themselves?

An undeniable truth is that, despite the initial excitement over seeing films in three dimensions, public interest has waned. Massively. The ‘3D take rate’ – that being the percentage of 3D revenue vs. the same films in 2D – has noticeably nosedived. From a relative steady peak around 2011 with a 54% take from around forty releases, the figures have dropped year-on-year to now accounting for a paltry third of the 3D/2D box office. (source)

The technology simply isn’t the headline act it once was. The desaturation of the image, the lack of consistency from one film (or one auditorium) to the next, and the general underwhelming evolution of the technology since Avatar are common complaints. For many, promises of a revolutionary new storytelling technique have not been kept. The public are voting with their ticket stubs, rejecting 3D in most instances.

Not that the studios are to be discouraged, however. RealD is very much the baby of the modern film industry, and it won’t be allowed to die without a fight. With the big studios holding an iron grip over both the audience and the exhibitors, many cinema goers are forced to make a choice between parting with extra cash for a peak time 3D showing, or viewing one of the sparser 2D versions nonchalantly shunted to an awkward-o’-clock time slot. With their biggest tentpole releases, the studios know they have the audience over a barrel. Want to see Avengers: Age of Ultron opening weekend at 8pm? You’re paying the 3D increment. Don’t like that? There’s a nice 10pm 2D showing. Don’t worry, you’ll be home by one in the morning.

It is a practise that works solely to benefit the studio, and keep the 3D fires burning despite a growing wave of opposition. Film fans are left out of pocket, and the cinema is left to deal with complaints about the lack of choice and customer satisfaction. In an industry seemingly already held together with duct tape and rubber bands, the divides this can create between distributors, exhibitors, and the viewer threaten to bring the whole thing crashing down. All the while Netflix looms in the background with a wry smile on its face.

Can it be put right?

There is hope. For all of the grandiose marketing spectacle surrounding Avatar, it undeniably lived up to Cameron’s hefty claims of scale, scope, and depth. Visually, there can be no doubt the experience was enhanced by finely-crafted 3D. How to Train Your Dragon, Toy Story 3, The Adventures of Tintin, Life of Pi – similarly wonderful examples of 3D done correctly; less objects flying out of the screen, and more focus on immersion and subtlety. More often than not, a clear indicator of a film dedicatedly shot for 3D, rather than retrofitted in post-production. The Last Airbender, Clash of the Titans, Green Lantern, and many others providing the haphazard yin to their far superior counterparts’ yang in this example.

Going back to Cameron’s quote at the head of this article, the key is comfortability, and conservatism. To make a great film, directors have to merge a myriad of visual, aural, and narrative elements. 3D is in a sense no different from cinematography, editing, or sound design. To tell a great story these elements need to be used tactfully and in tandem with one another. A great director understands this, and the difference between a good and bad 3D film will ultimately rest on how much the person in the chair engages with the true ideals of the technology. Physically shooting in 3D makes all the difference in this department.

What has unfortunately become a sour point with 3D, though, is that it is often allowed to overawe the other elements, becoming a garish visual gloss rather than a new layer of immersion and spectacle. An unfortunate by-product of 3D’s position as primarily a studio, rather than directorial, initiative. Simply, those that are best placed to use the technology effectively – the directors, the cinematographers, the editors – are not the ones fuelling the 3D fire. In many cases, such as with acclaimed directors Christopher Nolan and Danny Boyle, they are outright rejecting it.

Indeed, from James Cameron’s wide-eyed championing of 3D visuals, little else has blossomed other than creative apathy, viewer disinterest, and studio greed. The format, if it is to survive beyond mere financial stability, needs a shot in the arm from a group of creatives as passionate and as intricate as those that brought us Avatar and Life of Pi. 3D may yet re-establish itself as a wondrous tool for visual storytelling, but it will need a push behind it that transcends mere financial gain.

Grand landscapes, not retrofitted dioramas, sculpted with care and narrative integrity: Only when we, as viewers, are provided with more of that can we truly deduce the merits of 3D as a cinematic tool.

Do you prefer 3D films, or do you actively avoid them? Is the format still going to be around in ten years time, or will it peter out? Give us your thoughts in the comments section.

(top image: Life of Pi – source: 20th Century Fox)

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Graduate of the University of Portsmouth with a first class honours degree in film studies. For the last few years I've been managing a cinema and sharing my opinion on films with anyone who will listen. Previously contributed to The London Film Review, The Cult Den, Screen Robot, and Movie Marker.