Long maligned no matter the medium, the short film is often seen merely as a launching pad for bigger and better things. However, for documentarians, the short is almost the primary form, as it takes a lot of time, funding and quality footage to come up with a feature-length documentary worthy of release.

Thus, for documentary, the short is the rule rather than the exception, and the field is stacked with quality, potent films, more or less unhampered by typical commercial expectations. The documentary short is a dense, powerful form that has power to affect equal to that of its feature brethren, and in often less than half the time.

The nominees for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Short vary wildly in topic (if not tone), with stories that span a wide swath of human experience across the globe. It is unfortunate that these films are for the most part relegated to festivals and special screenings, since, as you are about to see, they represent some of the most powerful and enduring films of the year.

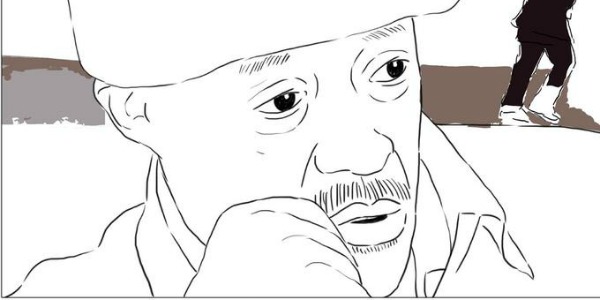

The Last Day of Freedom

Dir. Dee Hibbert-Jones, Nomi Talisman

Animated documentaries are certainly not unheard of, but they are about as rare as they are controversial. After all, how can one claim to be capturing reality accurately if doing so through such a consciously constructed medium? But if we recognize audio works as being valid documentaries, then animating them shouldn’t be inherently objectionable and is just an acknowledgement by the filmmaker of the story as a construction, rather than attempting to elide that fact. Add in that The Last Day of Freedom was actually rotoscoped, and you get a complex work blurring the distinction between objectivity and subjectivity that is at the crux of the film’s narrative.

The film is an interview piece with Bill Babbitt, who tells the story of his younger brother Manny being executed by the state of California in the infamous San Quintin penitentiary. It is unfortunately a not-unfamiliar story of a Vietnam vet returning home with PTSD and finding himself out of sorts with the society from which he sprung. Bill says, “Manny came marching home, limping mentally and morally”, and without any services or support, he ended up committing a murder under a state of mental duress. In telling the tale, one can see, even through the animation, Bill trying to relieve himself of the demons of guilt brought on by turning his brother into the police.

Another chapter in the book of the absurd American justice system, one of the most striking moments in Bill’s story is how marines were sent to the prison to salute a man sentenced to death and to honor him with a purple heart (a practice banned the next year). The animation, and its changing mediums, serve not only to illustrate the story, but to illustrate both Bill’s and Manny’s mental states. The film manages to pull off this clever trick successfully, creating an effective antidote to talking head fatigue. A reminder that justice, like most everything, is a fluid construct that ebbs and flows with the times, The Last Day of Freedom is an honest, challenging, and ultimately successful account of the causes and consequences of on man’s heart-wrenching decision.

Chau, Beyond the Lines

Dir. Courtney Marsh

War is often seen as generational, linking people of common age by the particular atrocity they were forced to endure (or in the case of the U.S., perpetuate). They are usually seen as something with a defined end: even if the conflict continues it just becomes a new war that will eventually come to cease before it is inevitably replaced. For instance, with the Vietnam war, we typically consider it to be the sins of our fathers, and that those impacted by the conflict to be of their generation. Chau, Beyond the Lines illustrates what a naive assumption that is, as it explores the world of contemporary victims of Agent Orange, which has remained in the country long after the last American boots left its grounds.

Starting off in a school built to accommodate those deformed by Agent Orange exposure, the film’s main focus is on the eponymous Chau, who in first painting with his feet, and then his mouth, seeks to transcend the walls of his assisted living facility to have as normal of a life as he can. Chau dreams to become a successful artist and fashion designer; “I always have to draw, I can’t stop”, he states as a matter of fact.

Surrounded by kids also afflicted by Agent Orange as guests are paraded through the facility to look at its inhabitants as though it was a zoo, Chau dreams to become a successful artist and fashion designer. “I always have to draw, I can’t stop” he states as a matter of fact. The film follows Chau as he navigates both his own abilities as well as the world in an effort to transition towards full independence.

The fact that children who have no reason to even know about the war in Vietnam are profoundly impacted by its occurrence decades past is both infuriating and a reminder that war is always a long-term proposition, no matter how long the actual battles take place. Those burdened with birth defects resulting from Agent Orange are so rampant in Vietnam, estimates range from 2-4.8 million (in a county of 90 million), that there is a national holiday to recognize them.

They are of the sort that it are hard to confront and uncomfortable to depict, but Chau, Beyond the Lines accepts the challenge well and does so with taste and empathy. Chau is an inspiring figure not just for Agent Orange children, or the handicapped, but for anyone that has every felt constrained by their surroundings and discovered necessity as the mother of invention.

Body Team 12

Dir. David Darg

Opening with a strong and surreal backwards handicam shot of a group of people in hazmat suits navigating a stretcher down a narrow alley, Body Team 12 is a stark and unforgiving account of the Ebola crisis in Liberia. Specifically, the film follows Garmai Sumo as a member of Body Team 12, a group charged with unenviable of safely removing corpses felled by Ebola from their homes and communities. “My life is a sacrifice for our country to succeed”, Garmai explains, as she is doing this gruesome job for the benefit of her son and his generation.

If that sounds like a heavy proposition, that’s because it is; between intensely grieving mothers and bodies leaking diseased blood wherever they lay, this is a heavy and long 13 minutes. While a clear and succinct depiction of exactly what a body team does and why Garmai chooses to be a part of it, the short running time of 13 minutes makes the film feel too dense with sorrow. This is serious material to be sure, but like its counterparts in the feature-length category, Winter on Fire and Cartel Land, the subject matter itself guaranteed something compelling and affecting so the real task was in how to convey that in an artful way.

In this task I feel the film comes up short and that its nomination appears to be more of an acknowledgement of the hard work depicted than the depiction itself. Perhaps Body Team 12 would have worked better with more room to breathe, but as it stands, the experience of watching it feels too much like a sledgehammer, offering the viewer little to no help in processing or contextualizing the human devastation it puts center-frame.

A Girl In The River: The Price Of Forgiveness

Dir. Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy

One of documentary’s greatest powers is to highlight cultures and practices outside of one’s own common experience. This can be done in a myriad of ways, but usually films of this nature offer something in the way of comparison so that the viewer can better relate to whatever it’s set to examine. This is utterly impossible in the case of A Girl in the River: the Price of Forgiveness, which takes for its subject something so outside of western cultural norms, familial honor killings, that it is difficult both to comprehend and to watch without becoming enraged.

Yet, seasoned Pakistani documentarian Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy manages to convey the topic with such nuance and empathy that it is difficult to watch A Girl in the River without steadily rising feelings of rage, indignation and disgust.

The film follows Saba, who fell in love with Qaiser, a poor neighborhood boy, and eloped with him. However, her uncle had wished Saba to marry his brother-in-law, so as a result he and her father attempted to kill her, and left her for dead in a river. She managed to survive and as a living victim now has the power to press charges against her familial attackers. But tragically, her family and community are not on her side.

Fighting the case in court, Saba is forced to go into hiding with her new in-laws. Her sister openly condemns her while her mother pretends not to have known. The word “honor” keeps coming up: Uncle Maqsoof – speaking from behind metal bars – claims everything is “about respect. what [Saba’s father Muhammad] did was absolutely right” In this society, leaving home is the greatest offense and thus all attempts to rectify such an act are entirely justified.

One might be quick to simply ascribe this practice to religion, but Saba’s attackers share equally in psychopathy as they do fanaticism. For instance, they blame Qaiser for their imprisonment, accepting no responsibility or remorse for their actions. “Islam does not permit a woman to go outside of the home”, they claim, never discussing its stance on filicide; they also display a grandiose sense of self-importance as they are happy to stay in jail for “honor and respect”, though they family remains chastised and destitute beyond the prison walls.

Facing pressure from all but her new family to drop the charges, which would entail her publicly forgiving her would-be murderers in court, Saba must decide whether to seek justice in order to curb this rising trend, or be silenced and have her father and uncle return to society not just free, but respected as well.

The values of the family and community here are so utterly foreign, sometimes it feels not like another country put another planet, that the viewer might be tempted to dehumanize and relegate them to the category of heartless villains. They may not be wrong in doing so, but when these individuals’ actions are not only not condemned but condoned by the community at large, one is forced to take a step back and contemplate what broader themes could be at play here, besides mental illness and misogyny. I definitely don’t have the answer to that question, but A Girl in the River does a stellar job posing it, in addition to bringing to light a horrific practice that it hopefully aids in stopping cold.

Claude Lanzmann: Spectres of the Shoah

Dir. Adam Benzine

Claude Lanzmann‘s Shoah is a film that looms large in the minds of those who love documentary, often discussed in academia but little seen in practice. Not only is it about probably the most dour topic possible, the Holocaust, but it also clocks in at a spit-take inducing nine and a half hours. Marcel Ophüls, director of the seminal documentary The Sorrow and the Pity calls it a masterpiece, but labels the filmmaker behind it a megalomaniac. Lanzmann effectively confirms that point by claiming Shoah not as a masterpiece of filmmaking, but of character.

Claude Lanzmann: Spectres of the Shoah provides an account of the making of this monumental work, directly from the man who made it. In that sense it is an important document both for film historians and those who study the Holocaust. Yet, the most riveting moment in Spectres of the Shoah are clips from the film itself, most notably a scene in which Claude gets his haircut by a survivor in a New York barbershop.

In talking about the shooting of that scene, Lanzmann comes across as nothing less than a master documentarian, knowing both how to provoke as well as capture a moment of pure sincerity. Lanzmann really pressed the barber to get him to discuss his horrible memories against his wishes, but it was worth it, stating that when the barber began to cry he felt his tears were “as precious as blood…they were the stamp of truth”. The viewer thus takes no small delight in the fact that Benzine later puts Lanzmann in exactly the same situation, coercing him to discuss an incident in Shoah‘s filming which he rather would not, the covert filming of Heinz Schubert.

Specters of the Shoah is full of interesting anecdotes and behind the scenes revelations , the appreciation of which would no doubt be aided by a working knowledge of the film being discussed. It actually did make me want to watch Lanzmann‘s film, which is impressive for someone who is subject to a mini-version of Shoah any time we have a family dinner with my cousins, but overall, the film feels more at home as a DVD special feature than among the nominees for best short documentary this year. Even still, it will endure as a novel account of one the most arduous productions ever, non-fiction or otherwise.

Conclusion and Prediction

The nominees for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Short are as indicative of the strength and diversity of the medium and the quality represented here rivals any five (or eight) films nominated in any of the other more prestigious categories. Having said that, my pick for the winner is A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness, which instilled in me as much emotion as anything I saw the past year without a character named Bing Bong.

I think this could be the rare convergence, especially rare given that documentary is the category voted on not by the relevant members (documentary filmmakers) but the whole Academy, of the film that should win and will win, since it has a social justice bent that Academy voters love. But this is a really tight race and I can plausibly see any of these films taking home the little gold guy. Whoever it is, I’ll go to sleep tonight happy in my assurance that the Documentary short is not only alive and well, but thriving.

Have you seen any of the documentary shorts? Which have you pegged to win?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.