Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey doesn’t really need an introduction. Even if people don’t know what it’s about, they will know something about it. They will have seen the monolith somewhere, or the clip where the bone turns into a spaceship. They’ll probably have seen that episode of The Simpsons based on the film. The original version of film was shot in Academy Ratio (aka 35mm), but the re-release has been altered to 70mm.

What’s New?

Basically, the screen has been reduced in size lengthways and increased in size width-ways. It’s a great aspect ratio for 2001 because it makes all of those sweeping shots of spaceships, sweeping vistas and large swaths of space that appear towards the end look that much better. Those things are part of the reason, despite the cold and oppressive nature of the majority of the film, it’s stood the test of the time. It’s a film that lends itself to the big screen very well: there’s as much scope in visuals as there is in its epic plot. If you’re going to watch it for the first time, this is the way to see it.

Truthfully, I do think the attraction of showing the film in 70mm as opposed to 35mm is only going to appeal to people whose job it is to review them, or people who wish it was. For everyone else, the fact that the screen is wider and smaller will be neither here nor there. But that doesn’t change the fact that it looks great, and I think fans of sci-fi are going to find a lot to enjoy in it.

The theatrical release is a little shorter than the version you’ll find on DVD and Blu-ray. The beginning of the theatrical release has a black screen over which Georgy Ligeti’s “Atmospheres” plays, which actually sets up the rest of the film pretty well, but the rest of the omitted scenes are things which not even the biggest fans would notice (parts of Dave running across the centrifuge of his ship, a section where a monkey looks at a pile of bones). There’s a reason those parts were removed. The theatrical release has none of the unnecessary extraneous stuff, and the film is better off for it.

What Does It All Mean?

It’s impossible to talk about 2001: A Space Odyssey without talking about what it all means. (There will be spoilers from this point onwards). People will talk about the film’s last act, aptly titled “Beyond the Infinite,” and “Through the Star-Gate” in Arthur C. Clarke’s novel which formed the basis for the film, ad infinitum. But it’s a sequence which is deliberately left unclear: Dave falls through a wormhole and witnesses stars exploding, a series of vast neon-lit mountain ranges and desert planes, then ends up in a classically-decorated room in which he appears to watch himself age, only to transform into a baby housed in a sharp white womb, watching over Earth.

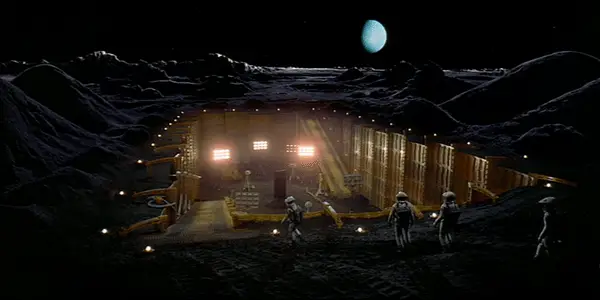

Beyond that, there’s no point trying to decipher what happens in those scenes, because they’re an exercise in theoretical physics. What’s important is the transformation Dave, and the gorillas, and the humans in the section which precedes the final act, go through. The action is all held together by one thing: the monolith. The monolith teaches the gorillas to wield weapons, to fight. In short, the monolith helps form a society among the animals, and the takeaway is that those societal concepts spread to a period far in the future, where humans have learned to coexist for the good of Earth. Again, the (or at least a) monolith is present, having been dug up from the depths of the moon. It emits a harsh ringing sound, and once again, humanity progresses.

Which is exactly what happens in the final act; the monolith floats through space above the surface of Jupiter, then appears in the room in which Dave appears to spend his dying days. That’s the last time the audience sees the monolith, but the takeaway is that the thing will appear again somewhere along the line.

To me, the question you’re supposed to ask after it’s all over isn’t what the monolith is, but why the monolith is. Who sent it? In the course of the film, you learn that the signal being sent to the moon came from Jupiter, but nothing more than that. There’s a hint that it may be alien activity, but in the world of 2001: A Space Odyssey there are no Little Green Men. The “aliens” that sent the signal, and the monolith, could be anything from people just like us to something closer to humanity’s idea of God: all-seeing, all-powerful, and completely focused on advancing civilisations. For what reason? There’s no way to know.

At its heart, 2001: A Space Odyssey is a film which reflects its writers’ anxiety about their place in the universe as more and more of it is unearthed. The film was released one year before Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon, and the fact that it was a conversation dominating the entirety of America is very present in the film; a secret excavation on the moon is the main catalyst for the film’s plot.

We knew where we came from, but nobody knew then what awaited us as we explored more and more of the galaxy, and we don’t know a whole lot more now. All of that anxiety seems to stem from the sheer size of the universe (which is a motif present in the film, from the whimsical scene involving the spaceships to the terrifying intensity of Dave’s journey through the infinite).

2001: A Space Odyssey: Conclusion

There’s a reason 2001: A Space Odyssey is considered one of the best sci-fi films of all time. It’s a film which asked questions which are as pertinent now as they were in 1968. No matter how much of the universe humanity conquers, there will always be parts which are unexplored. The experience of viewing the film is an intense one that requires a lot of concentration, but 2001 is something which will never go out of fashion. As long as there are people, it’s a film that will grace our big screens time and time again.

What are your thoughts on 2001: A Space Odyssey?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.