As with any dark chapter of history, the AIDS Epidemic presents a challenge to filmmakers who refuse to reduce the queer experience to one of suffering. It is, for lack of a better word, much easier to make a film about the pain and despair of the time, about the unparalleled devastation it brought on an entire generation, wiping out countless folks who could have been queer mentors and elders today. In 1985, Yen Tan resists any such essentialization of the era or the experience, opting instead to deliver a quiet but haunting portrait of a man faced with his mortality.

The film follows Adrian (Cory Michael Smith), a handsome, ostensibly successful man who returns to his hometown of Fort Worth, Texas for Christmas after spending years away in New York. From the moment he lands, we can sense the tension between him and his obviously much more masculine and conservative father (Michael Chiklis). At home, he is almost desperately embraced by his mother (Virginia Madsen) and coolly ignored by his younger brother (Aidan Langford), who has still not forgiven him for leaving him behind in Texas. Under pressure from his mother, he eventually reconnects with Carly (Jaime Chung), his childhood best friend and ex-girlfriend. Though things between them get off to a rocky (re)start, he eventually opens up to her and she learns the gravity of his situation.

Beyond Trauma

1985 is by all means a heavy and taxing film, but it pushes back against the kind of trauma porn that characterizes so much work made about horrific times in retrospect. It helps that Tan, despite growing up in Malaysia rather than America, approached the story from a deeply personal perspective. As a gay man who came of age after the epidemic had, more or less, subsided, Tan was close to many AIDS survivors. As he explained in one of the film’s packed screenings at SXSW, he wrote 1985 as an ode and elegy for that lost generation of queer men who did not make it through the epidemic.

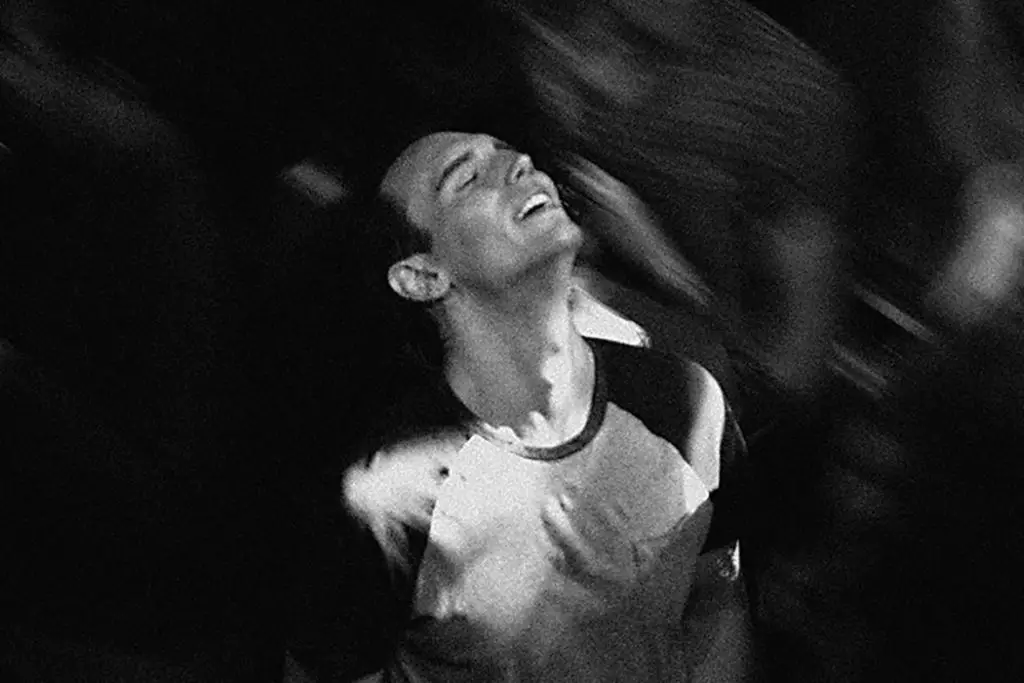

The whole film has a potent sense of grief and remembrance to it. It’s, obviously, devoid of nostalgia, but touches on the kinds of excitements unique to the decade, like slasher films and the Madonna Virgin tours. In spite of everything, Adrian remains capable of immense love and joy. He’s patient with his family, even as his father pushes his conservative agenda on him and his mother pressures him to pursue marriage. Tan doesn’t dismiss these unintentional micro-aggressions, as we see how they only further burden Adrian’s psyche. But Tan also extends an empathy towards the family that is somewhat rare in American queer cinema. Without validating their problematic beliefs, he situates them as products of their time and place, portraying them as two flawed people who, at the end of the day, genuinely want what’s best for their kids, even if they don’t know how to go about it.

Small Town Blues

Tan focuses most on Adrian’s relationship with his younger brother, Andrew – and for good reason. As soon as we meet him, Andrew has all the telltale signs of a kid who has never felt like anything but an outcast. He constantly asks Adrian if he thinks he is worthy of love or attention. He feels out of place and out of time. Adrian comes alive most in this heartwarming arc of brotherly love. Whereas Andrew could barely look at Adrian at first, he quickly comes to see him as the big brother he had always needed. Adrian introduces him to new music, takes him to an R-rated movie and emboldens him to be true to himself; his wants and needs. Thanks to a tight script, this never comes across as cheesy.

Adrian’s relationship with Carly is also heart-wrenching. From the moment they meet again, he is clearly desperate to confide in her, but every time he tries, he can’t seem to do it. Perhaps he’s prevented by shame, perhaps by distrust. Tan riddles the entire film with ambiguities and it works exceedingly well. This is a film that trusts your judgment and understanding. It is striking that Adrian never actually uses either the word “gay” or “AIDS,” but we implicitly understand what he is going through. Rather than loud revelatory moments, Tan depends on much subtler, more poignant expository scenes. In one of the most haunting and effective, we see Adrian chopping up onions in his kitchen when he accidentally cuts one of his fingers. It’s a small cut, nothing that worries his mother, but he freaks out, and asks her to hurriedly get him a first aid kit. While she’s away, he throws away the onions, the kitchen knife and the cutting board at that.

Tan’s choice to shoot in black and white works very well for this sense of period intimacy. As much as he wants to revisit the past, he also wants to keep its horrors at bay. Moreover, the notion of binaries inherent to the contrast of black and white acts as a super satire of the very mores Adrian’s conservative hometown pushes on him. As he and his family get to know one another better, they all, in the most quiet of ways, disavow this asinine sense of morality.

1985: Conclusion

1985 is a gripping reminder that the social drama need not be loud and tumultuous for it to be effective. Relying heavily on the personal over the historical, Tan has crafted a stunning love letter in memoriam for the queer big brothers who could not be there to tell him what Adrian tells Andrew.

1985 premiered at the 2018 South by Southwest Film Festival. Its release date has yet to be announced.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.