12 DAYS: A Compelling Look At People On The Edge Of Society

It took me a while to discover the wonderful world…

Raymond Depardon is a photographer, a journalist and a filmmaker, but, above all, his eyes view humans with compassion. He respects others and is kind with the reality of their lives.

The opening to Depardon’s IMDB biography is as poetic and concise a primer of the documentarian as you’ll find. The 75-year-old Frenchman has been making his compassionate, people-focused films for more than half a century, on topics ranging from the lives of French farmers (Modern Life), to the election of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing (1974, une partie de champagne).

His latest documentary, 12 Days, is centred around a French law stating that anyone admitted to a mental hospital against their will (sectioned) must have their case go before a judge within twelve days. That judge, who is not a medical professional, will then decide whether the patient is fit to reenter society.

The majority of 12 Days is taken up with these ‘trials’, and without any narration or onscreen commentary, we see the great variety of people who come through the system.

In Court

We spend most of 12 Days inside the (for want of a better word) courtroom, and as we see case after case, the pattern of these sessions soon becomes clear. First, the judge tells the patient why they are there. Then, they ask the patient questions about why they were sectioned, how their twelve days have gone, and if they think they’re ready to be released (they always say yes). Then, the patient’s counsellor fills in any important medical history information that hasn’t yet arisen, and presents the patient’s argument for release. Then, the judge decides whether or not to let the patient reenter society (they always say no).

One striking thing about 12 Days is the array of reasons patients have for finding themselves in this situation. One woman had a breakdown at work, and another two are suicidal. A man hears voices. Then there are the most severe cases, involving patients whose stays have been a lot longer than twelve days; a man who stabbed a stranger on the street thirteen times, and a man who murdered his father. Whatever the severity of their case, all the patients are treated with compassion by everyone in the courtroom.

It shouldn’t be a surprise, given the weighty subject of the documentary, that 12 Days can be tough to watch. Some of these patient’s stories are crushingly sad. None have had an easy life. The last case we see is a new mother, whose separation from her young child echoes what happened to her as an infant. It makes you wonder what her daughter’s life will be like. The pain of these people can be overwhelming.

And yet there is lightness here too. Their conditions make a lot of the patients quite blunt, and they do come up with some funny lines. One man, with a barely noticeable speech impediment: ‘I apologise for my lisp, but who gives a damn? Some people are mute’. Another requests help from a surprising source: ‘Contact Bernie Sanders and he’ll explain the situation.’ Depardon is never mocking towards his subjects, but appreciative at the offbeat way they see the world. In a documentary as frequently tragic as 12 Days, any sort of levity is a relief.

Out Of Court

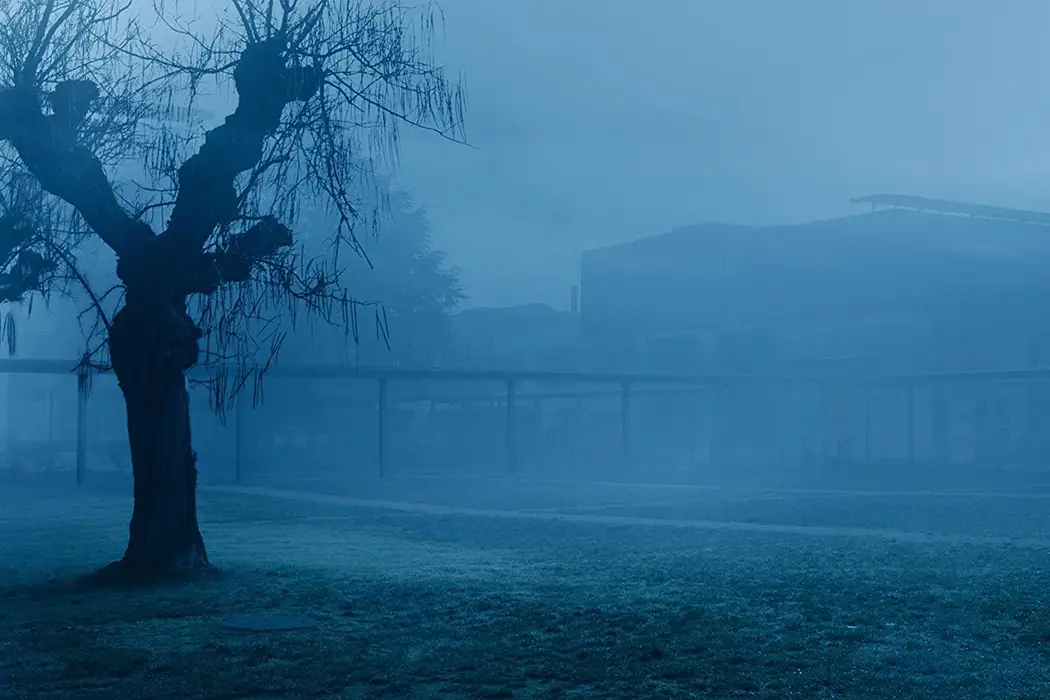

The court scenes are interspersed with explorations through the corridors and around the grounds of the hospital. As the camera roves, we see patients absently rocking, talking to themselves, and one pacing like a tiger trapped in a zoo. Most disturbingly, from inside the closed door of a room called ‘Salon D’Apaisement’, we hear the howls of a woman screaming about demons.

These sequences are filmed with the eeriness of a horror movie. The way Depardon‘s camera slowly prowls through the halls, the creepy, industrial whisper of the soundtrack (Alexandre Desplat‘s score doesn’t kick in fully until later in the documentary), and the screams of the demon-obsessed women combine to make the hospital seem like a terrifying place, and the patients people that you should be frightened of.

And that’s at real odds with the rest of the movie. The film opens with a quote from Michel Foucault: ‘The path from man to true man goes by way of madman’. Throughout the court scenes you are invited to empathise with the patients and the awful things they’ve suffered through to get to this point. They are always treated respectfully. Nothing else in the documentary suggests that Depardon would want to portray his subjects as people to fear, yet that’s how these scenes appear. It’s puzzling.

Direct Cinema

The odd atmosphere in these scenes is a rare negative side effect of Depardon‘s preferred documentary school, Direct Cinema. Rather than use voice-over narration and onscreen interviews, Direct Cinema documentaries do their best to just present reality as it is, without outside forces interfering and distracting from the truthfulness of the image. Though there’s a long-standing argument over the ethical practice of Direct Cinema and how genuine it can ever really be, the method has produced some excellent documentaries (Primary, Salesman, Titicut Follies), and is one Depardon has been working in throughout his career.

As we’ve seen, it has its drawbacks. When you remove the authorial voice, it can be hard to ascertain just what the director is saying. Then there’s the frustrating fact that we have no surrogate to ask the questions that we want answered. There is so much to pique your interest here, but Direct Cinema isn’t about satisfying curiosities. You get what you’re given.

Ultimately, though it does leave you with more ambiguities than you might like, 12 Days’ use of Direct Cinema approaches proves a good thing. Not being force-fed information is a much more rewarding experience than if Depardon were to have just run through a list of points he wanted to get across; any insights feel earned, and will vary from viewer to viewer. It’s a film that promotes discussion about both the specific events within, and the wider issues surrounding mental health and the law. The fact that you want to talk about 12 Days afterwards means that Depardon has done his job well.

In Conclusion: 12 Days

Whilst there are some scenes in 12 Days that make you wonder what director Raymond Depardon is trying to say, for the most part his documentary is an engaging exploration into the lives of people at the very edge of society, filmed with warmth, humour and humanity.

Have you seen 12 Days? What did you think?

12 Days is released in the US on March 16th. For further release information, click here.

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

It took me a while to discover the wonderful world of cinema, but once I did, everything just fell into place.