10 Movies With Low Ratings That Are Actually Good

Alistair is a 25 year old writer based in Cambridge.…

Cinematic failures appear in all shapes and sizes; some are critically acclaimed upon release only to become hated months later. Others get shunned by critics and audiences only to develop cult followings years later. In this day and age, where every other film has a sizable cult following, it is difficult to determine which films have truly earned their cult status. Based upon initial reviews and IMDb user ratings, here’s a list of ten poorly rated (6.0 or under on IMDb) films that are not the failures that you would expect. Of course, this is my own opinion – due to their statuses as failures, I’m sure that Film Inquiry won’t be pleased with me endorsing many of these movies on the site.

10. Freddy Got Fingered (2001)

In the YouTube era, when comedy sketches based around non-sequiturs are tickling the funny bones of younger audiences, a movie as universally hated upon release as Freddy Got Fingered begins to make more sense. The movie has built up a cult following of passionate fans who claim that the movie is essentially a post-modern art film, or an “anti-comedy”, that prioritises jokes over anything that makes concrete narrative sense. In the current climate, where Louis C.K. similarly uses the “it doesn’t have to make sense if it’s funny” template for his sitcom, Freddy Got Fingered doesn’t feel like anything as pretentious as an art film. It feels like the result of a man being given $14 million to make a movie, realising he’ll never be given that opportunity again and deciding to make the weirdest thing imaginable knowing that a major studio is picking up the cheque and will have to release it.

The movie doesn’t feel that unconventional today (to a British viewer, it often recalls the slapstick surreality of Vic and Bob or The Young Ones), but it still mines humour from unusual places; it isn’t offensive or trying to be, yet the laughter it provokes is mainly of the shocked variety due to how inexplicable most of it is. On a technical level, it feels like a formulaic Farrelly Brothers movie, of the sort that was the biggest earner in Hollywood comedy at the time, with lots of road trip sequences and an eclectic soundtrack of pop-punk and 80’s hits. Yet Tom Green takes pride in subverting the formula whenever the narrative needs to get underway; within the film’s first ten minutes, he breaks a conventional road trip narrative to inexplicably get out of the car to go and masturbate a horse. Questioning why this happens instantly stops it from being funny; Green knows this isn’t how any sane human being would act, but he does know that as lowbrow humour goes, it is pretty amusing.

Green doesn’t want to do anything as pretentious as “subvert the formula”, but instead to do something that he finds funny. In fact, the narrative as a whole only exists to get him to go places and do idiotic things. You kind of wish more comedies prioritised the jokes above the narrative, because after all, people aren’t going to be quoting scenes of exposition when they leave the cinema. Every line here is quotable in its own deranged way, to the point that although negative reviews were to be expected, it is surprising how many people have called it an anti-comedy. Instead, it is firmly anti-narrative; there is no logic to this film whatsoever, but considering how much it made me laugh (and also feel somewhat ashamed of laughing), why should that be a problem?

9. The Paperboy (2012)

After his previous film Precious was Academy Award-nominated, it was safe to say that the next major film project from director Lee Daniels was going to be highly anticipated. The adaptation of Pete Dexter’s 1995 novel seemed like a solid project to go into. Even Pedro Almodóvar reportedly wanted to direct the film as his English language debut. The movie would fit perfectly in Almodóvar’s filmography; a pulpy crime thriller with frequent moments of high camp, and also sex scenes that take great pride in being ridiculous.

The film Lee Daniels made actually feels little different to what the great Spanish director would have conjured up, yet it is undoubtably the best in Daniels’ filmography due to being the only one that is unashamed about its trashiness, with no pretensions at courting awards voters. However, due to being established as an awards-baiting director, when his movie premiered at the 2012 Cannes film festival it was met with a chorus of bemused boos, presumably a price you have to pay for following depressing social realism with cinematic trash of the highest order. Like Almodóvar’s filmography, The Paperboy frequently feels high camp to the point that it may spin out of control at any moment, turning a fairly routine crime procedural into something far more entertaining.

The film has a lack of style that perfectly compliments its trash status. Never before has the sweaty, humid stench of a film’s setting (in this case, 1960’s Miami) been captured so perfectly on film. Adding to the humidity are the constant sexual fetish themes, which you can imagine are what attracted Almodóvar to this project in the first place, as well as a gleeful perverseness in how it sexualises its characters at every opportunity (if you want to see Zac Efron in his underwear for long stretches of time, then this is the film for you).

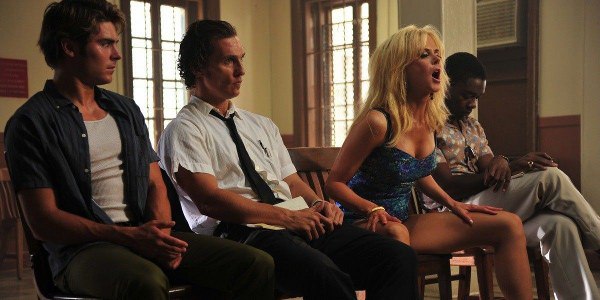

The Paperboy’s portrayal of sexuality is so alien as to how it is usually represented in mainstream cinema. Sex scenes are repeatedly played for laughs, with no inclination that the audience is supposed to find this attractive. It isn’t even grounded in a recognisable reality, with many plot points being the direct result of sexual perversion; a personal highlight is after taking Nicole Kidman to visit her husband (John Cusack) in jail, Efron, Matthew McConaughey and David Oyelowo have to spend the next few minutes sitting in awkward silence as husband and wife aggressively masturbate at each other from metres away. Scenes like this are deliberately played for laughs, but the tricky tonal tightrope Daniels is walking between a crime thriller and a campy send-up of an erotic drama means that many viewers assumed he wasn’t in on the joke. The Paperboy is a terrifically fun movie, and its derisive reaction upon release shows why so few American movies embrace campy eccentricity.

8. Spring Breakers (2012)

The closest we will ever get to seeing a mainstream movie from infuriatingly pretentious director Harmony Korine, Spring Breakers divided critics and audiences upon release, even though I seem to remember it having a far more positive response. The movie portrays a group of college students who descend into a life of crime to fund their holiday to spring break in Florida, descending even further into that lifestyle when they get there. The movie portrays spring break as the realisation of every hip-hop music video cliché come to life, and under Korine’s eye, it represents something approaching hell on earth.

Spring Breakers is frequently problematic, undoubtedly in the gender politics, but the end result is something very rare indeed – a modern movie that feels distinctively of its time. It is simultaneously a celebration and satire of hip-hop excess; James Franco, in a career best performance, delivers the definitive generational statement about self-worth in a monologue where he asks us to “look at his shit”- unlike most gangster rappers, he takes equal amounts of pride in owning Scarface Blu-Rays and multi-coloured shorts as he does money and “bitches”.

Despite showing all these characters at their worst, Korine still keeps a clinical detachment from them, ensuring we never see them as anything more than archetypes come to life. This is a decision that helps make the movie feel joyously surreal. Franco’s cover version of Britney Spears’ ballad Every Time feels all the more bizarre as it acts as a rare window into the character’s mindset. The main reason the film feels off its time is due to the ADHD editing techniques, making it feel more like a music video than the latest release from a divisive auteur, as well as the soundtrack that is constantly blaring from the opening scene. It is the definitive portrait of a detached and cynical generation, too in love with pop culture to realise the state of the world around them; maybe this is why it has been greeted by audiences with a similar sense of detachment.

7. The Cable Guy (1996)

As with most of Jim Carrey’s early work as a comic actor, The Cable Guy had him play a character who was annoyingly defined by his quirks. However, director Ben Stiller uses Carrey’s typecasting to his advantage; here, we get to see the dark excesses of the character (only a slight variation on the quirky types Carrey was known for playing), as well as grounding this character in a reality that explains why he acts this way and why people aren’t reacting to him in the way that many audience members would.

As a dark satire of media addiction, the movie was ever so slightly ahead of its time, especially since many viewers weren’t ready to watch a comedian like Carrey in a role that stretches the limits of his likability to breaking point. Although the movie doesn’t consistently hit the satirical targets it aims for, The Cable Guy is far from being a bad film. It is frequently inspired and, like the initially annoying character Carrey plays, proves to be a far more interesting movie as it progresses, twisting genres to its will. It is still the most ambitious movie Stiller has directed.

6. Drop Dead Fred (1991)

The sole American movie to star anarchic British comedian Rik Mayall in the lead role, Drop Dead Fred has been seen by many young audiences since its 1991 release due to the appealing story about an imaginary friend from a woman’s childhood returning to cause havoc, as well as giving Mayall’s slapstick talents a home in a family-oriented vehicle. What is surprising to learn is that the movie received a wholly negative response, with Gene Siskel naming it the worst film of 1991. Even though when I watched it from an adult perspective, the film stood up well when I saw it again recently. However, this is likely because Mayall’s shtick is so familiar to British audiences, whilst it will prove annoying and off-putting to foreign ones.

A major reason I feel Drop Dead Fred is far better than a run-of-the-mill slapstick comedy is because it deals head on with the themes of mental illness, whilst Fred also represents the manifestation of emotional abuse. At times, it is difficult to watch, borderline depressing even, that these elements are being played for laughs. Yet this helps form why it holds up as an adult viewer; it plays as a solid character study into psychological and emotional abuse, one that is engaging to the point that it seems irrelevant if the film is no longer as funny as you thought it was when you were a child. The movie was almost remade a few years ago, but thankfully it wasn’t. After all, the things that make Drop Dead Fred interesting are not the things that make it an easy sell, and a reliance on the slapstick would destroy what makes the original a better movie than it has any right to be.

5. The Counselor (2013)

Ridley Scott has spent the last few years putting an end to being classified as one of the greatest directors of all time; he was once the man behind Alien and Blade Runner, but now he’s the man behind Prometheus and a plethora of bland Russell Crowe movies. The Counselor should have placed him back in the pantheon of all time greats, yet it was universally derided upon release, leaving him to fall back on the big budget “director for hire” projects that are increasingly synonymous with his name.

I’m honestly puzzled by the reaction to the movie; it is the screenwriting debut of Cormac McCarthy and, by his standards as author, plays as business as usual. It is the exquisite marriage of low art, with an exploitation-themed narrative about a drug deal gone wrong, with high art, as all characters speak (like they do in most McCarthy texts) long and ponderous dialogue dealing with the very nature of evil. Michael Fassbender’s eponymous (yet forever nameless) counselor keeps getting told, via extensive monologues, that his drug deal is going to go badly. When it does, Brad Pitt’s character reacts by breaking into hysterical laughter.

Nobody in the works of Cormac McCarthy speaks like a regular human being, and it is all the better for it. It helps give The Counselor the edge over many similarly-themed exploitation movies. It isn’t original by any means, but the fact that McCarthy is writing for the screen and not having his work adapted by screenwriters gives it an edge over other adaptations of his work – this is pure, undiluted McCarthy. He was criticised in some corners for clearly not having read a screenplay in his life, and having his characters interact in ways that are completely alien at times. Yet, married with the grindhouse-inspired narrative, the film proves innovative and endlessly thrilling. Like the Coen Brothers’ Millers Crossing, it uses the artifice of the genre-specific dialogue to create a hermetically sealed world separate from ours that these characters live in, where people actually behave and interact like this. Yet to focus on the dialogue, as many critics have done, is to overlook the sheer excitement of the action, as few mainstream movies take this much joy at subverting the norms of action cinema. And for a journeyman director, creating something subversive is exactly what Scott needed to do to get his career back on track.

4. Only God Forgives (2013)

One of the better reviewed “bad films” on this list, director Nicolas Winding Refn’s follow-up to his mainstream breakthrough Drive suffered from expectations that suggested this was going to be more of the same, only set in the world of underground boxing in Thailand. Of course, the film is nothing of the sort; it is a hallucinatory exploration of familial vengeance that is actually perfectly aligned with the more experimental entries in Refn’s filmography. But after the mainstream breakthrough, people were surprised that he had gone back to his more uncommercial sensibilities. The disappointment is bewildering, as in its best moments, Refn successfully creates a sense of surrealist dread matched only by David Lynch or Alejandro Jodorworsky (who the film is dedicated to). More importantly, it never feels indebted to the works of these filmmakers, creating something very distinctively unique to Refn and proving to be one of the few films of recent years that is genuinely incomparable.

Full of scenes that I’m still thinking about two years after I saw it (twice) at the cinema, it may suffer from severe style over substance, but it succeeds effortlessly at creating a movie that feels like a cinematic experience you have to rush to see at the biggest screen possible. Only in Refn’s mind can something as mundane as a man singing karaoke become one of the most enigmatic and spine-tingling sequences of recent years; that he achieves this level of surrealism whilst staying true to the bone-crunching exploitation violence that he’s famous for is an unparalleled achievement.

3. Showgirls (1995)

A lot of the films on this list have been the result of much critical reevaluation since their original release, and none more so than Showgirls, director Paul Verhoeven’s attempt at making a big budget exploitation satire of the seedy Las Vegas underbelly. Taken at face value, it is easy to understand its reputation as a camp classic; this is a film where the dialogue increasingly sinks to such lows that a scene of two women bonding over their love of eating dog food is one of the least strange elements. Yet, Verhoeven has actually succeeded, even though he has claimed, in interviews following the film’s disastrous release, that he failed. This is a clear satire of lowbrow sexploitation, where anything remotely sexual is turned up to such ridiculous levels that it is impossible for any audience member to be attracted by it.

Showgirls‘ portrayal of hypersexuality is as alien and otherworldly as anything in a David Cronenberg film, leaving you to question why anybody would be turned on by the manipulative strip club culture. Yet, it also covers its tracks by playing out as a straight-faced exploitation movie, complete with questionable subplots involving sexual abuse, that make it appear he is not in on the joke. The performances and the dialogue scream over-the-top camp, yet on a technical level, the film is far from disastrous; every single detail here, in particular the fondness for tracking shots, is part of Verhoeven’s distinctively controlled vision. Written as a pitch black comedy, yet incorrectly received by critics and audiences as a serious drama attempting to expose the exploitation in strip club culture, Showgirls was always doomed to fail. When watched now, understanding the dark satirical vision behind it, it plays like the knowing camp-comedy it was always intended to be.

2. Ishtar (1987)

One of the most infamous big budget flops of the 1980’s, Ishtar’s reputation as a terrible film appears to be solely based on how much of a production nightmare the film was. Elaine May’s comedy stars Warren Beatty and Dustin Hoffman as two awful musicians who find themselves caught up in the middle of a conflict in Morocco. After initially believing they have been asked to become the house band at a hotel, we soon realise that the CIA are using them as unwitting pawns to overthrow the government of the neighbouring (and entirely fictitious) country of Ishtar. During production, costs for the action-comedy repeatedly inflated, due to May’s famously demanding status as a director and on-location shooting at a time of real life political tensions in Northern Africa. The much-publicised production nightmare resulted in a box office catastrophe, as well as a butchering from critics. Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel named it their worst film of 1987, whilst May won the Razzie for worst director.

In the years since, the film has gained a cult following (Quentin Tarantino, Martin Scorsese and Edgar Wright all speak highly of the movie), yet not as big as one as you would expect. Firstly, the film is a clear inspiration to Flight of the Conchords, in its depiction of socially awkward and musically inept performers, with a healthy dose of the same dry wit that has helped Bret and Jemaine become international cult sensations. The songs are deliberately bad, with songwriter Paul Williams claiming that he had the most fun writing music for this movie than any other throughout his long and eclectic career. Soundtrack aside, the movie’s influence can also be felt in many modern comedies; after all, didn’t a film about two socially inept media types who are unwittingly hired by the CIA to overthrow a government become one of the most controversial films of last year?

1. The Room (2003)

The title of this article states that every single one of the films included here is, in some way or another, “pretty good”. The Room, however, lives up to its reputation as one of the worst films ever made. Yet, it is a train wreck of such magnitude that, like many viewers, I have got more enjoyment out of rewatching it for the millionth time than I have watching many legitimate masterpieces. The best way to experience Tommy Wiseau’s directorial debut is to watch it with unsuspecting friends, not giving them any context for the film or any explanation for what they are about to watch. When watched like this, The Room is the gift that keeps on giving. Right from the start, the film is perplexing to the casual viewer; little would they expect a film to have three softcore sex scenes within the first 15 minutes, two of which are blatantly using the same footage edited slightly differently.

Then there are the bizarre soap opera style plot twists that are never mentioned again once brought up, the fact that a blatant European man is playing an American with a thick foreign accent and, above everything else, the dialogue, which appears to be written by a man who has never heard human beings speak before. It is a testament to the bizarre line readings that a man screaming “I did not hit her!” becomes a hilarious non-sequitur instead of a hard hitting revelation to drive the story forward.

Wiseau now claims that The Room was a deliberate attempt to make a comedy, but thankfully, this is just a lie, covering up his deluded aspirations at making what he believed was a hard hitting social realist drama that he intended to use as a platform to become the Tennessee Williams of the 21st century. Watched now, the insanity of The Room feels like a bargain basement answer to Gone Girl, with similar themes of women plotting against their partners and a subversion of soap opera style melodrama; here, the subversion of soap opera style melodrama is simply in the bizarre writing, acting and directorial choices. Generations of bad movie lovers will forever be grateful to the extent that Tommy Wiseau failed with The Room, even if it did tear apart any chance of him ever getting taken seriously as a writer/director.

Are there any low rated movies that deserve to be on this list? Which movies don’t deserve a critical reevaluation?

(top image: Ishtar – source: Columbia Pictures)

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Alistair is a 25 year old writer based in Cambridge. He has been writing about film since the start of 2014, and in addition to Film Inquiry, regularly contributes to Gay Essential and The Digital Fix, with additional bylines in Film Stories, the BFI and Vague Visages. Because of his work for Film Inquiry, he is a recognised member of GALECA, the Gay & Lesbian Entertainment Critics' Association.