They say if two’s company, then three’s a crowd, but I like crowds, especially when they’re crowds of gangster movies from countries around the world. So this is our third outing (first here, second here), and if my editor doesn’t kill me, there might be a fourth.

Yes, there’s crime in every country, and where there’s crime there are criminals, and when they get organized they become gangsters, and if said country has a film business chances are they will make gangster movies. Whether or not we glorify, deify, vilify or romanticize these scofflaws of the screen, one cannot deny the power and sustainability of gangster film.

In some ways, the genre speaks for itself, but it doesn’t always speak back in the same language. Without a doubt, we will always bow to Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese and the contributions from Brian DePalma, Quentin Tarantino, and the Hughes Brothers, but the movies just get more interesting when you have a hard time pronouncing the director’s last name.

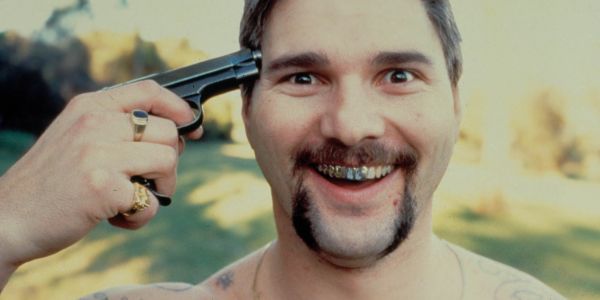

1. Chopper (2000, Australia)

After falling in love with the elegiac western The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, and the even more dour gangster film Killing Them Softly, I learned that Andrew Dominik’s directorial debut was a grimly sardonic about the real life criminal Mark ‘Chopper’ Read, a role played by Eric Bana no less.

Unlike the “smarter” outlaws who try to allude the authorities, Chopper Read made it his mission to become a celebrity in his life of crime. And the obvious metaphorical (if you can even call it that) meat of Chopper is the fact that the existence of the film ingratiates and slightly satirizes the celebritydom of gangsters.

Outside of the sociological implications, Chopper is a gloomily entertaining exploration of the recklessly destructive titular gangster, and the lives of small time hoods in the Australian criminal underworld. Mark Chopper Read isn’t smart or cunning, but as a gangster he’s one hell of a showman.

Dominik has a proclivity for moody realism in recounting the exploits of a self-stylized criminal, but he also manages to find room for a very, very dark sense of humor.

2. Salvatore Giuliano (1962, Italy)

Hollywood has the capitol on gangster movies, and more specifically mafia films are usually the most popular. But when you go to their country of origin, you get a more actualized depiction of organized crime. The raw and unadorned style that followed Italy’s neo-realist movement perfectly suits the material in Francesco Rosi’s fable of famed Sicilian gangster Salvatore Giuliano.

Shot eleven years after Giuliano’s death, director Rosi proved to be a strong storyteller and stirring political commentator in his direction of the proletariat citizens who organized themselves with the help of the titular bandit, who became a hero in Italian culture, specifically to the Sicilian region. The evident Marxist implications places an emphasis on society’s ability to achieve a collective goal rather than the actions of one individual.

Employing non-professional actors, shooting on locations where specific events had taken place, casting Sicilians involved with the recreated historical events; the catharsis on Rosi’s part to piece together the life and death of Giuliano shows us a film that is a combination of neo-realist fable and investigative docudrama. He looks at the not-too-distant past with a nonlinear narrative structure, beginning with the iconic image of Giuliano’s violent death to his rise as one of Italy’s most heroic partisan guerrillas.

3. A Prophet (2009, France)

The relatively honest cliché about a life of crime that you hear is usually “you either end up dead or in jail.” Well, witness protection is the third option, but that’s not exactly pertinent concerning the film A Prophet. So if you’re not riddled with bullets, or living a new life under the name “Guy Incognito” in Omaha, Nebraska, what happens to high profile gangsters behind bars?

A Prophet best answers that question, as it revolves around the machinations of gangster life in prison: how they maintain hierarchy, manipulate guards, murder people, traffic contraband, and so forth. But in the tradition of narrative storytelling, A Prophet is told from the point of view of Malik, a 19-year-old of Algerian descent, who turns into an unlikely ally to the Corsican syndicate after he is forcibly cornered into murdering a Muslim inmate. The prison is divided among the Corsican and the Muslim population and Malik swears allegiance to neither but plays off of both sides for survival – is he a victim of circumstance or an elite strategist?

A Prophet is an interesting turn for a gangster film because we have a feature-length treatment of a subject that is usually a narrative component of the genre. Most movies use prison as a B-story, or a conclusion to a life of crime, whereas A Prophet takes place almost entirely behind bars.

Like any skilled storyteller, Jacques Audiard uses the fertile environment of confinement as a way to explore France’s relationship with the Muslim populace, as well as touch on ethical questions about identity, race, loyalty and (of course) the ineptitude of the prison system that seems to breed criminals rather than rehabilitate them. Audiard utilized the genre in the most intelligent way by providing us with perceptive material that stands as a platform for countless interpretations.

4. The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933, Germany)

Fritz Lang has so much clout as an auteur and architect of technical expressionism that it frequently overshadows our ability to realize that this massively influential movie is, in fact, a gangster film. Sure, it’s reductive to merely brand it as such, but it does revolve around a titular character who operates a criminal empire through a network of gangsters. This and M (another film that could qualify as a gangster movie) are staples on any international cinema syllabus, so it’s understandable why it’s not thought of as a “gangster” film. But in all actuality, it’s a quintessential gangster epic.

What’s fascinating about The Testament of Dr. Mabuse is the precision and detail Lang invests into the procedural realism throughout; of course, it’s impossible to discuss, really, anything about Fritz Lang without some historical notes. While his flight from the Nazi party as well as Goebbels’ propaganda machine is exaggerated, it was this film that mirrored the pending fascist machinations on the horizon. Political implications aside, Lang had laid out the blueprints for the gangster film just as much as the police procedural, shifting attention to both legions of organized criminals and police and the detail and precision that they dedicate to their work.

So much can be said about this film, but it’s strange that the title seems to be overlooked, when the crux of its existence hinges on a genre that modern audiences don’t associate it with. When you synopsize a movie whose titular character has used his last will and testament as a coded blueprint for a criminal empire as he’s dying in an insane asylum, the psychological implications (along with Lang’s visual expressionism) tend to overshadow the rest of the film. Yet, shifting your focus to the criminal element is a rewarding way to reappraise a celebrated classic.

5. A Better Tomorrow (1986, Hong Kong)

John Woo set the world of action ablaze with his mesmerizing 1989 film The Killer, and upped the ante three years later with Hard-Boiled. Before these polarizing classics, he channeled his experience in traditional wuxia genre to the world of contemporary triad gangsters by putting two Colt .45s in Chow-Yun-fat’s hands, a change from the dual sword-wielding heroes that populated his earlier films such as Last Hurrah for Chivalry.

Triad gangsters were already familiar subjects in film, and Woo infused the ethical stoicism consistent with the work of Jean-Pierre Melville, which was further complimented by the visual bravura of Akira Kurosawa and Sam Peckinpah. John Woo’s stylistic innovations revolutionized action cinema time and time again, but here is where it started.

A Better Tomorrow uses classic themes of family honor and betrayal to their greatest potential as a vehicle for expertly staged shootouts and action sequences. While the body count in this outing is low compared to the director’s other films, A Better Tomorrow still dwarves any Hollywood actioner when it comes to stylized violence.

Never oppressive, excessive, or redundant, bullets fly through anonymous henchmen while bright red blood squibs explode, and the heroes have never looked cooler. Slick, stylish, bold, violent and smart, A Better Tomorrow is truly one of the best.

6. Onibi The Fire Within (1997, Japan)

Kinji Fukasaku made yakuzas frighteningly realistic, Takeshi Kitano brought the genre into an expressive and artistic territory, and then Takashi Miike went into the valley of cartoonish ultra-violence with the genre – but in between all of these pioneers is the unsung (or lesser sung?) Rokuro Mochizuki. Like contemporaries Miike, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, and Shinji Aoyama, Mochizuki broke out with a handful of stylish but paced and somber yakuza films in the 1990s with Another Lonely Hitman, Mobsters’ Confessions, A Yakuza in Love, and his best film to date: Onibi: The Fire Within.

The film stars Yakuza movie veteran Yoshiro Harada as Kunihiro, a yakuza hitman released from prison who makes an attempt to reform his life and go straight, yet finds himself at odds with the criminal element in contemporary society. Instead of the garish violence of Takashi Miike, or the graphic realism of Kinji Fukasaku, Mochizuki decidedly opts for a more relaxed pace, taking time to let characters develop and giving an expanded sense of mood and place than most films of the genre. Rokuro Mochizuki is a special case, bringing a mature essence of drama to a time when Japanese cinema was for curiosity seekers in search of video nasties.

Quiet, romantic, and meditative but not without moments of gritty action, Onibi: The Fire Within comes from a director whose distinctive style reinvigorated the yakuza genre once again.

7. The American Soldier (1970, Germany)

Rainer Werner Fassbinder was literally a movie-making machine, and this early title is an important notch in his belt as a director. It shows us that Fassbinder wasn’t just a powerhouse of a filmmaker but also a force to be reckoned with, not to mention his locomotive-powered drive to direct that would sadly run out of steam before his time.

Fassbinder’s affection for the genre is evident, even from his first feature film, Love is Colder than Death, a lean and mean gangster movie which (despite the awesome title) is evident of a strain on the shoestring production. That’s not to say that Fassbinder had millions at his disposal for The American Soldier either, but the final product is more refined, and his focus toward paying homage to the classic Hollywood noir films pay off. The film remains one of the director’s best early efforts. It deals with themes (that were already mainstays in his oeuvre) of displacement and immigration, under the umbrella of his multifaceted treatment of Germany’s postwar social climate.

Inspired by the Hollywood film Murder by Contract, Fassbinder had written The American Soldier as a stage play a few years previous. While the original script was a blueprint, his pulpy noir treatment revolved around a Vietnam veteran who returns to Munich only to become a contract killer for the mob.

The American Soldier is a witty and referential piece of filmmaking that takes advantage of its self-awareness yet maintains some genuine levity regarding the genre as well. While Jean-Luc Godard was breaking every rule he could with films like Breathless and Band of Outsiders, Fassbinder was shaking up European cinema in his own way, though his execution yields a more respectful treatment of the genre.

8. Gangs of Wasseypur Parts 1 & 2 (2012, India)

These two film series are best watched as one mega saga, chronicling decades of the “coal mafia” in Dhanbad between three major families over the span of fifty years. Since theaters wouldn’t screen a 5-hour plus film, it was then split into two 160-minute parts.

Coming from a country mostly known for lavish musicals, we see precious few Bollywood movies in North America nor do we associate gangster sagas with Hindi cinema. But Gangs of Wasseypur is a stylish and ultra violent epic that has the chops to rank alongside or surpass other gangster films, regardless of their country of origin.

Watching these two films back-to-back can be a challenge given the running time, but there’s plenty of assassinations, raids, stabbings, and robberies to go around, making it a very quick 319 minutes. Though the habitat of Dhanbad might feel unfamiliar, criminal practices in India don’t differ that much from anywhere else in the world. Gangs of Wasseypur plays out an intricate web of characters without shying away from exposition or narration, and all while retaining a quick and witty sense of punchy style.

Characters come and go, allegiances are made and broken, and years of family disputes can be difficult to keep track of, but there’s plenty of dirt bike drivebys, assassinations, invasions and cool musical cues to keep you entertained in Gangs of Wasseypur.

9. The Harder They Come (1973, Jamaica)

Long before rapper beefs, Twitter wars, and Suge Knight dangling people out of windows, no one had so brilliantly used their profile as musicians as an allegorical depiction for exploring public glorification of outlaws. The Harder They Come uses the parallels of show business with crime, showing us that the two might not be all that different.

People will most likely remember the explosively popular soundtrack of the same name from Jimmy Cliff, a classic that brought reggae/ska to the states and predates Bob Marley’s universal breakthrough. But director Perry Henzell and Jimmy Cliff captured lightning in a bottle with their pairing of sound and image in this rough hewn production that stands the test of time. It also might be one of the few times you’ll hear “neo-realist musical gangster film” in one sentence.

Cliff plays more or less himself, whose criminal activities were inspired by real life outlaw/folk hero Rhyging, cited as the original rude boy. After cutting off a record with a crooked producer (again, not too much of an exaggeration), he turns to a life of crime when he’s facing corruption from all sides of Kingston. The church, police, drug dealers and impoverished economy turns Ivan into a gun-toting gangster, who the public adores.

Like many intelligent gangster movies, The Harder they Come gives us social and political implications regarding the criminal element.

10. Snatch (1999, United Kingdom)

Guy Richie made a name for himself with his wise-cracking debut Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels. For a debut, it layered down the foundation for the stylist that we are now familiar with. But if you ask me, Snatch is the most fun of the director’s gangster cannon.

The film has an international cast of new faces who would go on to become stars, such as Stephen Graham, Jason Statham, and former football star Vinnie Jones, alongside familiar faces like Dennis Farina, Brad Pitt, and Benicio del Toro, who bring an enormous level of energy to a loaded script written by the director.

Amid the glut of Tarantino clones that polluted the late 90s into the early 2000s (Things to do in Denver when You’re Dead, The Boondock Saints, Suicide Kings), Snatch showed us that Richie was more than just a one-trick pony who had a successful debut. Sure, Guy Richie is taking cues from directors such as Tarantino and Martin Scorsese, but Snatch has proven to stand the test of time and remains witty, fast-paced and exciting.

It’s not a perfect movie; it might rely on style over substance and the dialogue is just a bit too clever at times, but Snatch is still a colorful and exciting experience. We’ve seen Guy Richie go from his humble beginnings to bringing the consulting detective to the big screen (once again) and rebooting the famous Cold War era The Man from U.N.C.L.E. series. Divisive attitude towards his body of work aside, Snatch is an undeniably entertaining outing defined by the culture from which it came.

With one of the most electrifying opening sequences in the history of the genre, home or abroad, the first ten minutes of Snatch are a qualifier.

Conclusion

Sure, it’s more of the same genre, but when you look at cinema internationally, regardless of where you’re from, the lines blur, expand and in some ways contract depending on the cultural climate of the country in question. The economical/political implications are also at play; in the gangster films from South Korea, for example, you’re more likely to see political tensions concerning their neighbors to the north, which play a part in the proceedings. In the case of the Gangs of Wasseypur series, it shed light on the Coal Mafia (or Mafia raj) in India, a facet of organized crime I didn’t know existed.

While it might seem reductive to focus on such a specific facet of filmmaking, the gangster genre is one that speaks almost every language, and has the ability to both inform and entertain.

Some movies glorify crime, others not so much. Does it seem like gangster movies made outside of Hollywood glorify crime more or less?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.