Film Inquiry’s Greatest Films Of The 21st Century

Alistair is a 25 year old writer based in Cambridge.…

When the BBC polled an international array of critics, producers and filmmakers for their greatest films of the 21st century, there was naturally an outpouring of frustration on social media. The list was naturally derided for being elitist, not featuring any comedies and for featuring few works by female directors; textbook stuff when it comes to polls of greatest films.

When the list was announced earlier this summer, the Film Inquiry team initially agreed on doing our own gigantic top 100 to rival the BBC’s official findings. But, like most “best of” lists, that would come across as mere click-bait. Instead, as an independent film publication that takes great pride in the differing opinions of its writers, we are sharing our individual top 10 lists instead of collating them into one giant list.

Here are our opinions on our favourite movies of the century so far.

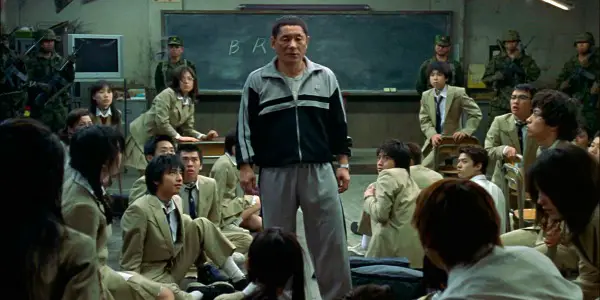

Alex Lines: Battle Royale (2000, Kinji Fukasaku)

Just coming in at the dawn of this interesting century, Kinji Fukasaku’s final film is a brilliant mixture of gratuitous violence, political commentary and multi-character storytelling. After a lengthy career of defining yakuza films (Battles Without Honor and Humanity), historical epics and traditional samurai films, Fukasaku’s last film was an adaptation of the hugely popular Battle Royale YA horror novel.

Set in Japan during an undefined future, an unstable society on the brink of anarchy has forced the government to try extreme measures to control the new unruly youth that are running rampart throughout the nation. This is the basis for Battle Royale, an annually televised event where a classroom is randomly selected, placed upon an anonymous island and the students are forced to fight each other to the death till one student stands, winning their freedom.

What makes Battle Royale so great is the amount of elements that Fukasaku effortlessly pulls off, making more than just a simple Japanese exploitation film. As seen often in cinema (most recently with Suicide Squad), it can be quite difficult to successfully juggle a large ensemble cast of characters who each have their own subplot, whilst telling a coherent story with enough screentime/importance without it feeling bloated, meandering or confusing.

Within two hours, Fukasaku manages to condense multiple volumes of Battle Royale into one tight package that flawlessly shifts through a multitude of different emotional beats that never feels stilted or unearned. A violent masterpiece, Battle Royale is one of the great films of Japanese cinema, starting off this century in a terrific fashion.

(The rest of Alex’s Top 10: Memento, The Raid, Snatch, Superbad, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, The Dark Knight, John Wick, Children of Men, Punch Drunk Love)

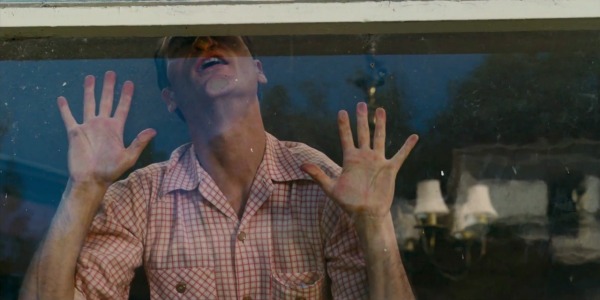

Alexander Miller: There Will Be Blood (2007, Paul Thomas Anderson)

What can I say about There Will Be Blood? That it’s one of the greatest films of the 21st century? That it made Paul Thomas Anderson more than an Altmanesque raconteur, not the idiosyncratic wunderkind but a solidified artist, a force to be reckoned with who graduated from multi-character mosaics to stark, ethereal elegiac character studies? There Will Be Blood is a revisionist western like no other anchored by one of the best performances, from one of the best actors of any era Daniel Day-Lewis. An enigmatic character, Daniel Plainview is sadistic, manipulative, and homicidal, and yet we hang onto his every word no matter how deplorable.

Only when he is matched by a charlatan, a self-described holy man, Elijah Sunday, whose shrimpy psychosis is enlivened by Paul Dano (a crime he wasn’t Oscar-nominated) Plainview might be volatile, but Sunday is the most dangerous, as he thinks he has the Almighty on his side. Jonny Greenwood‘s atonal score is pulse jumping and unnerving – if he scores every Paul Thomas Anderson film, I’m okay with that.

The very title There Will Be Blood almost seems prophetic, biblical, and the Sunday brothers only reinforce that likeness, although Dano as twin brother Paul Sunday appears only briefly it’s hard to ignore the connection to the Paul, the false Apostle. Sure, Paul Sunday does in fact lead Plainview to a place that yields blood in titular and a literal sense, but the ruinous fallout that occurs after all is said and done makes him something of a false prophet. There will Be Blood is, in my opinion, a perfect film.

(The rest of Alexander’s Top 10: Carlos, The Assassin, The Wind That Shakes the Barley, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Los Angeles Plays Itself, Pan’s Labyrinth, Traffic, The New World, Zodiac)

Alistair Ryder: Pan’s Labyrinth (2006, Guillermo Del Toro)

The only reason I’m writing film criticism today is because of seeing Pan’s Labyrinth. Sure, I’d loved movies before I had seen it, but it wasn’t until after my 14year-old self had seen Guillermo Del Toro’s visionary fantasy masterpiece that I became passionate about cinema.

Having grown up on fantasy franchises, from Harry Potter to the Lord of the Rings, I was immediately drawn to the bleak, adult fantasy world that transported the most mythical fairytale concepts imaginable and transported them into the misrerabilist reality of post Civil War Spain. I had never seen anything like it before; it was equal parts terrifying, exciting and moving, becoming my favourite film before I’d even finished watching it for the first time.

Because of Pan’s Labyrinth, I immediately became a movie nerd, but I’ve never seen a movie as good as this since. It is the high watermark of the fantasy genre, that is unlikely to ever be bettered. I couldn’t have asked for a better introduction to the delights of world cinema.

(The rest of Alistair’s Top 10: Scott Pilgrim Vs The World, 12 Years a Slave, Oldboy, The Social Network, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Let the Right One In, There Will Be Blood, In Bruges, Boyhood)

Arlin Golden: The Master (2012, Paul Thomas Anderson)

When I came out of an advance 70mm screening of The Master, I felt as though I had never before seen a movie quite like it. Anchored by transcendent performances from actors at the top of their craft, the film has an energy all its own: driving, frenetic and intimate, it defies genre. Director Paul Thomas Anderson took the subtle absurdity that peppered There Will Be Blood and brought it a little more into focus, before taking it front and center in Inherent Vice.

Frequently utilizing close-ups and centered by small moments, such as watching a young girl ride the tricycle, enjoying a favorite brand of cigarette, or casually fornicating with a sand-woman of your own creation, what makes The Master so special is that it’s an epic tale, told on a human scale.

Its magnificently flawed protagonists, crossing paths on an entirely chance encounter, signify opposite ends of the Freudian spectrum. Freddie Quell (Phoenix) is pure Id, running on little more than base instinct, while Lancaster Dodd (Hoffman) is the super-ego, striving for perfection, completing one another. The Master is a beautiful treatise on platonic love, with all its aesthetic elements entirely in sync, suggesting the humbling thought that there are no answers and we’re all just making it up.

(The rest of Arlin’s Top 10: Mulholland Drive, Spirited Away, Queen of Versailles, There Will Be Blood, Adaptation, Samsara, A Serious Man, Requiem For a Dream, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind)

Benjamin Wang: The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2013, Isao Takahata)

The Tale of the Princess Kaguya is an awkward and unwieldy movie, caught between the illogic and broadness of a fairy tale and the drive toward specificity and individuality that often pervades Isao Takahata’s work. (This is sometimes just a clever ploy on his part, letting him have his cake and eat it too.)

It whisks us out of intense, sorrowful moments without resolution and returns us to where we were before. It strains to cram an entire world’s worth of adventure in one brief sequence at the end of a sterile, cagey life. It plays happy music over a tragic scene in which arrows transform into harmless flowers mid-flight.

It’s not Takahata’s only film (and probably not his “smartest”) that struggles with contradictions between reconciliation and time, but it’s possibly the most urgent. It’s also the most intuitive and most involving, between the materiality of its drawings and the warmth in its soft colors and trembling outlines.

(The rest of Benjamin’s Top 10: 35 Shots of Rum, Spirited Away, Noriko’s Dinner Table, Yi Yi, Mulholland Drive, Moolaadé, Inside Llewyn Davis, Zodiac, Moonrise Kingdom)

Emily Wheeler: Million Dollar Baby (2004, Clint Eastwood)

Selecting a list of favorite films is really about defining what you want from a movie. There will always be more astounding films than you can list, so the ones you separate out should have something that hits you so hard you can’t forget them. For me, my favorites are the ones that rattle my emotions awake. I’m a rather dispassionate person, and thanks to low-level depression, my life is experienced in a dull monotone.

I treasure anything that cuts through that, so my list is filled with movies that jar my feelings loose. Million Dollar Baby tops them all because it’s the only film to ever make me cry over a human character. They aren’t tears of pain or joy, but of hope.

Like so many boxing films, the fights that matter aren’t in the ring. Maggie and Frankie are struggling to find lives that satisfy them, and by slowly allowing them to build something good together (not perfect, but good), the film strikes of note of realism that I find aspirational. The victory comes when Maggie, facing the end of her life, claims that she got what she needed. I believe in her peace and satisfaction, and I cry because I hope that I and everyone I know will have that moment when we reach our ends.

(The rest of Emily’s Top 10: Upstream Color, A Separation, How To Survive a Plague, Pan’s Labyrinth, The Perks of Being a Wallflower, Certified Copy, Mommy, 4 Months 3 Weeks 2 Days, The Assassination of Jesse James)

Laura Birnbaum: Spirited Away (2001, Hayao Miyazaki)

In Spirited Away, Hayao Miyazaki masterfully voyages through the intricacies of a young girl’s mind as she explores the innermost and endless possibilities within herself. We accompany Chihiro as she wanders through a dreamlike world composed in frames that seem to extend further than what we see – a world filled with fantastical creatures whose personalities exceed the confinement of their illustration.

Rich colors and imaginative environment and creature designs are not only integral to the visual language of the film but to the illustrative meaning behind it. As the movie progresses, the bathhouse and characters within it become an elucidatory replica of Chihiro’s emotional landscape (featuring that classic baby-in-the-attic metaphor we all know and love). Like many of his films, Miyazaki molds this story around heavy historical concepts that are easily overlooked at first glance. When I first watched it at age 11, I didn’t grasp these subtextual references, but I was still profoundly impacted by it.

I saw strength in Chihiro’s vulnerability and sought comfort in her ability to emerge from the emotional pain of loss into sincere empowerment. It is just as easy now as it was when I was 11 to immerse myself in the dark and wondrous world that captivated me at such a delicate time. Spirited Away is a parabolic fairytale undeniably drenched in allegory, but the real magic is in its ability to enchant its audience – even if its audience is being re-enchanted for the 100th time.

(The rest of Laura’s Top 10: Zodiac, The Witch, Oldboy, Eternal Sunshine, American Psycho, Lost in Translation, Queen of Versailles, Her, The Incredibles)

Lena Hanafy: Amélie (2001, Jean-Pierre Jeunet)

For me, Amélie solidified my love for all of film. Though it may seem like the stereotypical French pick of the bunch, my personal connection to this film transcends any form of pretension. Partly due to the timing in my life in which I watched this film, the definitive, exuberant, surreal stylisation of the whole film taught me something no other movie had up until that point. Not only did it bring to my attention the role of the director, but, more importantly, the potential of filmmaking.

Amélie stretches the boundaries of what is possible in cinema, Jean-Pierre Jeunet proves that a filmmaker does not need to follow a specific Hollywood formula to pander to audiences in order to be successful. Instead, he is unashamedly bold, simply by daring to be himself and, in doing so, channeling a completely original framework for filmmaking which no other can emulate. Amélie celebrates individuality and artistry and, I believe, encourages all aspiring filmmakers to strive for originality and push the boundaries of what is ‘normal’ and ‘successful’ in film.

(The rest of Lena’s top 10: Atonement, Stoker, In The Mood For Love, The Lives of Others, Cloud Atlas, Shame, Song of The Sea, Mary and Max, Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance)

Manon de Reeper: Spirited Away (2001, Hayao Miyazaki)

Spirited Away is an intricate film, with complex characters and story. It’s magical, it’s intelligent, it’s surreal, deeply embedded in Japanese folklore; it has little star-candy eating soots, dragons, ghosts, witches and it all still makes perfect sense. I’ve come to appreciate the film more and more with each viewing – from the music, strong and brave Chihiro, the vibrant colours, to its allegories and its world where gluttonous, self-centered adults are turned into pigs – it’s all utterly magnificent and a new nugget of wonder is uncovered every time you watch it.

Spirited Away is very unlike any Western animation film; it doesn’t have the hyperbolical “and they lived happily ever after” ending, like most Disney films. Even though it’s probably more magical than any Disney film, it’s also more realistic in establishing that not every story has a happy end, or that the way to get to the end isn’t necessarily happy. In real life, growing up and exploring what’s “out there” is a great (but sometimes scary) adventure.

Spirited Away is a terrific piece of art. It cemented Miyazaki as a true master of the cinematic arts, and no other film in recent years has come close to its brilliance.

(The rest of Manon’s Top 10: Children of Men, Mad Max: Fury Road, Oldboy, Pan’s Labyrinth, Minority Report, District 9, Song of the Sea, Lost in Translation, No Country For Old Men)

Mike Daringer: Inglourious Basterds (2009, Quentin Tarantino)

For me, Inglourious Basterds epitomizes the best of postmodern cinema and ideals. Revision is the name of the game, and with Tarantino’s 2009 World War II epic, he rewrote the end of the war and history itself, making for several fascinating insights about fiction and how films play into how we deconstruct and reinvent our particular worldview.

Firstly, by spelling both words of the title wrong, the movie signifies an offense meant to cut at conventional wisdom and what is considered the appropriate usage of language and grammar. Words become psittacism as time goes by, and there needs to be a subversion of traditions to help form new, purported significance in meanings.

Secondly, by blatantly throwing the historical accuracies out of the window, Inglourious Basterds seeks to redefine film as the art-form of documentation. What is shown, or replayed, is a preserved bit of the present that appears to the viewer as the past, though highly altered and edited for the affectation of sensory pleasure. And how does the story in Inglourious Basterds end? In a movie theater that burns down the old, accepted hallucination in favor of a better fantasy that is as much of an illusion as common history.

Tarantino gets this, and uses the film’s self-proclaimed masterpiece as a fully-aware retrospective. It’s pure entertainment that simultaneously comments about the narrative form, while making sure the viewer understand the importance of cinematic linguistics. When else have you seen a film in which people watch a movie in a theater, about a historical act, that has been filled with many intentional fallacies to heighten the reality of mental recall? Never. That’s why I think it’s the best of this century.

(The rest of Mike’s Top 10: No Country For Old Men, The Wind Rises, The Social Network, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Mad Max: Fury Road, Inception, Jodorowrsky’s Dune, Team America: World Police)

Siobhan Denton: Rust and Bone (2012, Jacques Audiard)

Rust and Bone is a remarkable film. A film which, in the hands of a lesser director than Jacques Audiard, could have easily become hackneyed and clichéd, yet through Audiard’s remarkable skill becomes something quite beautiful. Starring Marion Cotillard and Matthias Schoenaerts, the film’s narrative is derived from an amalgamation of two short stories by Craig Davidson. Audiard’s film intelligently selects inspiration from both, and in turn, creates an original and entirely affecting story.

Stéphanie (Cotillard) is an orca trainer, working at the local marine park. She meets Ali (Schoenaerts) at a nightclub early on in the narrative when, working as the nightclub’s bouncer, he is compelled to intervene in a physical altercation between Stéphanie and a fellow nightclubber. Despite the pair’s obvious attraction to one another, they do not meet again until Stéphanie, having experienced an accident while working, takes it upon herself to make contact.

It would have been easy for Audiard to fall back on tired tropes when representing both love and disability, but the film avoids this and in turn creates a truly progressive depiction of a physical disability. Rust and Bone is, with its premise and direction, almost fairy tale-like, yet consistently grounded in realism.

(The rest of Siobhan’s Top 10: The Master, Mulholland Drive, The Tree of Life, Lost in Translation, American Hustle, Fish Tank, Bright Star, Blue Valentine, Drive)

Sophie Cowley: The Master (2012, Paul Thomas Anderson)

I fell in love with The Master from the opening shot. The cinematography is basically flawless and makes you feel like you are watching a moving painting. Philip Seymour Hoffman plays the role of Lancaster Dodd, the leader of a cult who claims to free people from emotional trauma and suffering. I honestly think this is Paul Thomas Anderson and Philip Seymour Hoffman‘s best film collaboration in existence. Anderson had really crafted his own style by this point in his career and his confidence as a director is clear in the way he evokes intensity from actors, including Joaquin Pheonix and Amy Adams.

I was completely blown away by Phoenix’s performance as the drunken, nearly animalistic Freddie Quell, and was taken by his story. We also saw a new, darker side of Amy Adams in this film, which was very exciting. Overall, there is so much to be discovered in The Master: the film itself is like an exercise in psychotherapy, with its structure and narrative grounded in theories of psychoanalysis and scopophilia. The film is historical science fiction meets high-art drama. The score is beautifully haunting and makes you want to run off to sea.

(The rest of Sophie’s Top 10: Eternal Sunshine, Kill Bill Vol 2, Under the Skin, Coraline, Frances Ha, Boyhood, Ida, The Great Beauty, Submarine)

Stephanie Archer: The Dark Knight (2008, Christopher Nolan)

There are movies in everyone’s lives that have made them laugh, cry and just simply found a place in our hearts. For some, it’s a movie that constantly gives them a cathartic release, while others hit your funny bone causing laughs long after the movie has ended. For me, The Dark Knight is that movie. I feel I must be honest that there is a biased in my selection of the best movie of the 21st century as Christopher Nolan ranks at the top of my list of directors in Hollywood and Batman – well, he is the best comic book hero to ever be created.

With all this aside, I do believe that this movie still reigns supreme over the past sixteen years of film. The Dark Knight is a cohesive example of the passion and soul of filmmaking. Led by an astounding adapted script and brought to life by passionate direction and Oscar-worthy performances, this film firmly stands out above all the rest. Christopher Nolan, along with his brother Jonathan Nolan, have been writing brilliantly original and creatively adaptive films since the late 1990’s. Building off this strong foundation, Nolan leads his cast and crew capably, crafting an exceptional work of art that is captivating from is first opening scene until the final credits begin to roll.

Heath Ledger‘s performance is not only the height of the Dark Knight trilogy, but the height of this actor’s multi-faceted career. His passion and soul surge through every moment his character is on screen. He is an everlasting reminder of how far people are willing to go for their art form – no matter the consequences. Looking back on years past, a variety of exceptional films come to mind. Yet, The Dark Knight continues to stand high above them all – every element setting a standard not only for filmmaking, but for the heart and soul that goes into it.

(The rest of Sophie’s Top 10: The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, Star Wars: The Force Awakens, Inglourious Basterds, Winter’s Bone, Whiplash, Inception, Brooklyn, Seven Psychopaths, Love Actually)

What are your favourite movies of the century? What gems have we overlooked?

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Alistair is a 25 year old writer based in Cambridge. He has been writing about film since the start of 2014, and in addition to Film Inquiry, regularly contributes to Gay Essential and The Digital Fix, with additional bylines in Film Stories, the BFI and Vague Visages. Because of his work for Film Inquiry, he is a recognised member of GALECA, the Gay & Lesbian Entertainment Critics' Association.