Wheat vs. Chaff: 10 Elements of Quality Film

Graduate of the University of Portsmouth with a first class…

From the tiniest blog to the inked pages of Empire magazine, society’s devotion to film coverage highlights just how deeply moving pictures resonate in modern culture. It’s why you’re here reading this very article right now.

The finances back it up too. In the US alone, box office figures have exceeded $10 billion each year for the last six – and that’s not even considering home media sales and online streaming subscriptions. Yet, with the ever-rising cost of simply living in this world, what is it that makes moviegoers part with such excessive amounts of money for the privilege of a fleeting two-hour experience?

Films being great, that’s what. Well…the great ones anyway. Sure enough for every Citizen Kane, there’s plenty of Movie 43s, but just what is it that really distinguishes the two? In a world filled to the brim with subjectivity, opinion, and squabbles over Oscar results, just how do we pinpoint a ‘great’ film? What is it that the more mediocre films are lacking?

Whilst there may be no perfect recipe for quality film, looking for the following ten points of merit is probably the best way to start.

10. Visuals

Comparing a film with a book may be ‘apples and oranges’ to most sensibly-minded adults, but the cultural milieu will be damned if it isn’t going to go ahead and do it anyway. “The book is always better,” they cry, but that is never necessarily the case. One of the overriding merits of film over the written word is that unique visual experience, that opportunity to dissect a single frame and all that’s featured within, and come to a chapter’s worth of conclusions about the characters or events.

Good cinematography allows the audience to feel via the use of colour and setting. To be immersed in the imagery. To derive pleasure from sheer stylisation. A picture paints a thousand words, as the idiom goes, and the greatest of filmmakers have this visual storytelling down to a tee: Stanley Kubrick, Christopher Nolan, Guillermo del Toro, Peter Jackson, and all of cinema’s notable royalty.

Film is predominantly an experience for the eyes, and our obsession with bigger and clearer screens stems from this desire for the perfect image. That is ultimately why, of all films, it is generally those that craft a distinct visual style that stay with us the longest. Think of the harrowing opening scene of Apocalypse Now, the slick colours and street cinematography of Drive, or the technicolour lunacy of The Grand Budapest Hotel. Each example distinct in its approach to the moving image, but each no less memorable or effective.

9. Sounds

Ah, the other great trump card in the films vs. books debate. Great sound can elevate a film far and beyond its visual counterpart, working in tandem to illicit the right feelings at the right time. Even in the silent era, filmmakers understood the importance of a live musical accompaniment to complete the experience. Today, you’re going to need a beefed-up surround sound system to go with the gigantic TV if you want to enjoy the film viewing experience for all its worth.

Whether via a stirring orchestral score, such as in Hans Zimmer’s Oscar-nominated Interstellar soundtrack, or in the absence of sound almost entirely, a la 2001’s ominous space walk scene, great filmmakers know how to manipulate the aural sensation to generate the emotions that drive the story forward. Directors frequently work with the same composers, film after film, for a reason: they understand the power of the perfect score, and rely on seamless collaboration with one another to create the perfect tandem between music and visuals.

Sound effects, too, help craft a film’s identity. Much of what makes Star Wars what it is, is sound designer Ben Burtt’s legendary work crafting the now iconic blaster sounds and lightsaber whirs. That simple, but instantly recognisable, aspect helped the franchise blossom from generation to generation, endlessly parodied and homaged in pop culture even four decades later.

8. Characters

Travis Bickle, Severus Snape, Hannibal Lecter, The Joker, Ellen Ripley, Ferris Bueller. As diverse and contrasting a list as that may be, they all share a commonality: films driven by the complexity, depth, or charm of their characters. When we think of great films, we instinctively think of one or more of the characters within that made it so. What is Die Hard without John McClane and Hans Gruber? Leon without Mathilda? A Tarantino flick without, well, basically any one of its memorable ensembles?

Though we often do not realise it, we do not invest in a story because of the plot. What happens is almost always inconsequential compared to who it happens to. It is why a film such as Inside Llewyn Davis can garner such critical acclaim despite, relatively speaking, not a lot happening. On the flip side, films driven exclusively by ideas at the expense of characterisation often appear convoluted, and ultimately uninteresting. Think Wally Pfister’s recent directorial debut Transcendence, or the similarly-themed Lucy.

A fleshed-out, three-dimensional character ‘hooks’ the audience, and creates a bond that transcends a need to simply see them blown-up, shot at, or triumphant over the enemy. We care about them. Friend or foe, that character’s personality has us intrigued . No mean feat when you consider we may have only ‘known’ them for a couple of hours. It is that instant impact – the work of fine writing and acting – that separates great characters (and ultimately great films) from mediocre ones.

7. Ambition

Though it is often hard to convince naysayers otherwise, filmmaking is an art form. Its evolution, like any art form, owes it all to the pioneers of the craft, those who push the boundaries of the medium with career-defining moments of inspiration. Think of how films have evolved: from silence to Jurassic Park, from black and white to Avatar, from standalone pictures to the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Without ambitious filmmakers, none of this progress would be possible, and we would never see anything new rise to prominence.

Take Boyhood, for example. Richard Linklater’s coming-of-age story, filmed over twelve years, had no Earthly right to be made. Its premise is so outlandish and grandiose in its scale that it borders on being completely non-fundable. Yet, despite sound reasoning, Linklater’s ambitious labour of love was given the green light. Well over a decade later, the rewards are being reaped with immeasurable critical acclaim and awards acknowledgement all over the world. Were it not for that ambition and drive to achieve something new and special, Boyhood’s Oscar nomination may have fallen to something much more generic and ‘safe’. Mr. Turner, perhaps?

We, as an audience, recognise and reward achievement through ambition. Even the act of merely making a film displays a tenacity that deserves admiration. Those that push the envelope a little further however – be it through tackling challenging subjects, experimenting with form and presentation, or scaling new filmic heights – claim their place amongst the greats.

6. Identification

It is often said that film holds up a mirror to society. Though the characters and events may be outlandish, set in a fantasy realm, historical, or even computer-generated, the greatest of films know how to tap into the psyche of the audience and find those cherished nuggets of identification within. If we can empathise with a character’s situation, his or her arc serves a much more validating purpose that stays with us for years to come.

In cult classic Shaun of the Dead, the protagonist begins the film in a situation familiar to much of its target audience. Shaun is in his thirties, stuck in a dead end job, the romance fading from his relationship, wasting his days away at the local pub. What is ultimately gratifying about his development as a character, is that he works through these issues and finds purpose. The fact that this happens alongside the fantasy situation of a zombie apocalypse is irrelevant – merely a comic aside for real, human life crises.

It is not uncommon. A character we can relate to is ultimately a character we care much more genuinely about, and good screenwriters know this. This can be observed across all manner of genres, time frames, and even species. A lot of the success of the rebooted Rise of the Planet of the Apes is owed to the character of Caesar, whose distrust and backlash against the human populous bears much resonance to the frustrations we bear against our own ‘superiors’ in life. Caesar may be an ape, but his character arc is quintessentially human. That level of identification allows the audience to contextualise and sympathise with his actions, driving the immersion of the narrative.

5. Interpretation

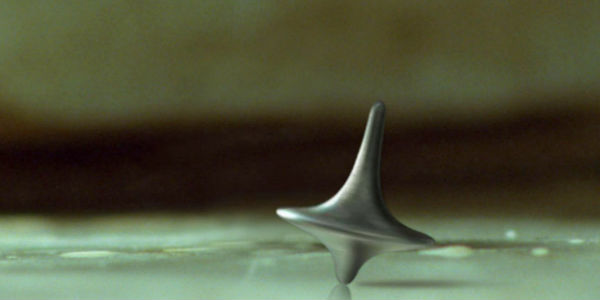

The experience of watching a film needs to outlive and outgrow merely just the time we are sat watching it. The thought-provoking debate provided by some of history’s more head-scratching films has helped preserve their standing in society, ensuring we are still discussing them many years later. This is ultimately born from open-ended interpretation. When two people can watch the same film and come to drastically different conclusions about its message, it is indicative of a level of depth that surpasses the average.

The example image above highlights the infamous final scene of Christopher Nolan’s Inception, the spinning top Leonardo DiCaprio’s character Cobb uses to decipher dreams from reality. As the top wobbles, the scene cuts to black. There is no definitive answer to whether Cobb is dreaming at that point, and more importantly, Cobb’s actions provoke discussion as to whether or not that is even important to him at that stage. The internet still dissects and argues the film’s resolution to this day, its place in recent pop culture as one of the most iconic open endings solidified.

Donnie Darko, Mulholland Drive, American Psycho, Pan’s Labyrinth – all examples of films that have been interpreted, re-interpreted, debated, and analysed with a variety of conclusions drawn. Whilst considered excellent films in their own right, their longevity owes much to how their stories can be contrastingly perceived.

4. Emotion

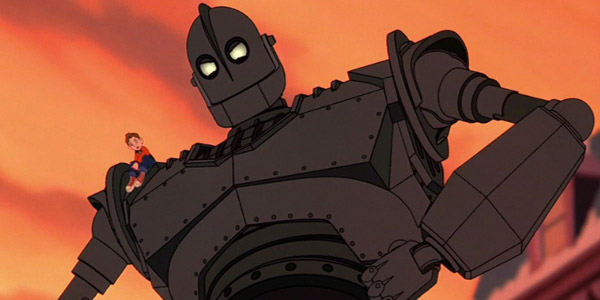

The lifeblood of any narrative form, the presence of emotion within films truly separates those that stay with us from those that fade away. We may not always remember the exact plot details of a film, but if the filmmakers achieve what they set out to achieve, we will always remember how the experience felt. Watching a film should be an emotional venture, be it through joy, sadness, or both.

Brad Bird’s animated adventure The Iron Giant is a key example. Focussing on the close bond between two dramatically mismatched characters, the film continually tugs at the heart strings as their relationship develops. The audience becomes emotionally invested in the duo, making the Giant’s ultimate sacrifice at the film’s conclusion all the more gut-wrenchingly sad. The memory of shedding tears watching that unfold as a child stays with me to this day, and acts as a constant reminder of how powerful cinema can, and should be.

It is a common trope in Hollywood, the ‘tear jerker’, but emotion isn’t always about eyes welling up. The audience needs to feel the characters’ every success, failure, heartbreak, and sense of injustice. An ‘uplifting tale’ is only so if the emotional cues are right. Syncing the protagonist’s emotional arc with our own is of course no easy task, but success in that area often distinguishes films that resonate from films that dissipate.

3. Pacing

Films are a unique storytelling medium in that the flow of the narrative is dictated at source, rather than by the receiving party. A book can be sped or slowed to fit the reader, a film will plough through and expect the audience to adapt. This is by no means a bad trait, and in fact one of the strongest aspects of uncontrollable immersion the medium has to offer. However, like all entries on this list, its success balances on a knife-edge.

This is pacing – the combination of direction, editing, and screenwriting that ensures the tempo of the film satisfies the action and successfully engages the audience. If a scene seems either to ‘drag’, or to skimp by too quickly, that is a pacing issue. Recently (and perhaps controversially) I observed this problem plaguing Oscar nominated American Sniper. Though the film had some devastatingly effective ‘slower’ scenes, it often got bogged down in them, leaving an awkward juxtaposition with its pacier counterparts, and ultimately, an uphill struggle for the audience to fully engage.

That is not to say that slow-burnt scenes are not a pivotal point of suitable pacing. In Pulp Fiction, we follow a large variety of characters and events, in non-chronological order, with Tarantino focussing a great deal on character development through seemingly inconsequential, lengthy exchanges of dialogue. In that case lay a perfect example of expert pacing, relaxing into its character development, but injecting vitality with more up-tempo scenes when needed.

2. Re-watchability

The best films do not get viewed once, twice, or even three times. They are constantly re-watched, re-scrutinised, and re-interpreted years after release. A great film will have many layers, many subtle hints towards stories untold, and much analytical depth. A single viewing can never be enough to absorb all a film has to offer. Be it to contextualise the resolution of the plot, to better explain a ‘twist’ ending, or simply to experience once more any of the previous factors mentioned in this list, great films demand you watch them again and again.

It is an issue I have had with a lot of Oscar contenders over the years. Rarely have a begrudged a film its place amongst the Best Picture list, yet equally rarely have I ever found myself revisiting the nominees years after. Excellent films, in theory, but lacking the inspiration for a second watch. Crash, The King’s Speech, Slumdog Millionaire – all guilty of this. This year, I fear contenders such as Boyhood and The Theory of Everything may fall the same way.

With David Fincher’s Fight Club, however, there is no such problem. I have watched that film (best guess) twelve times. Each time I come out of the experience feeling as if I’ve unearthed something new. An extra layer, detail, or interpretation that adds a vital strand to the narrative. Most importantly of all, not one of those repeat viewings has been tackled with anything resembling obligation. A cornerstone of greatness.

1. ‘Je ne sais quoi’

Whilst I hate to refer to such an idiom, much of what makes film great is indefinable. Film is art, and even the finest art scholars will bicker about what makes one painting greater than another. Film is no different. On a personal level, there are films I love that barely adhere to any of the previous nine criteria defined in this article. Similarly, there are films ticking most of those boxes that I won’t give the time of day to anymore.

Recognising that a film is technically great does not assure its position within a personal selection. There may be no logical reason why I would much rather watch Scott Pilgrim vs. The World than The Artist, but that is most definitely the case. Be it through a uniquely identifiable charm, a personal resonance, or factors completely unexplainable, certain films will always have that little something extra.

Above everything, true greatness can only be derived by the viewer, and we rarely ever sing from the same hymn sheet in that department.

Conclusion: What Makes Film Great

There is no exact science to this. Film is as subjective and as personal as any art form. Throughout this article I have mentioned films I consider to have excelled in the discussed category, but I wouldn’t for one second sit here and expect complete agreement about the examples I have provided. You are all wonderfully creative minds, with your own distinct taste and personal proclivities. There are no doubt hundreds of examples spinning round in your head.

It is why film criticism exists in the first place: the sharing and contrasting of ideas over the brilliant and the bland. The very idea that two intellectual minds can interpret a series of moving pictures so differently empowers the medium, preserving at least the notion that if we cannot agree on the merits of a single film, we can at least come to terms with what makes films, as a whole, bloody fantastic.

Do you agree with my choices? What do you think makes for a great film?

Please share your thoughts below!

(top image: Inception (2010) – source: Warner Bros. Pictures)

Does content like this matter to you?

Become a Member and support film journalism. Unlock access to all of Film Inquiry`s great articles. Join a community of like-minded readers who are passionate about cinema - get access to our private members Network, give back to independent filmmakers, and more.

Graduate of the University of Portsmouth with a first class honours degree in film studies. For the last few years I've been managing a cinema and sharing my opinion on films with anyone who will listen. Previously contributed to The London Film Review, The Cult Den, Screen Robot, and Movie Marker.